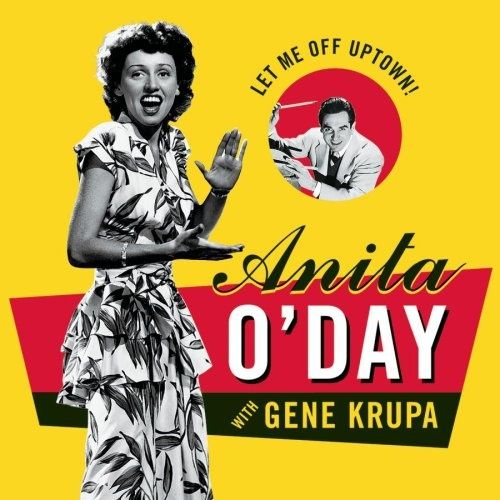

Singer Anita O'Day burst onto the big-band scene of the early 1940s with drummer Gene Krupa's orchestra, launching what would prove to be a legendary career.

Anita O‘Day began her career as a dancer in the Depression walkathons, making money by staying on her feet for days and nights at a time. In Chicago Gene Krupa discovered her singing in a nightclub and invited her into his big band, where she and trumpeter Roy Eldridge rocked the show-business world of 1941 with "Let Me Off Uptown." She would go on to record other swing-era hits with Krupa and Stan Kenton, and then a stunning series of small-group and big-band albums for Norman Granz‘s Verve label in the 1950s. Her vo-cool style influenced a whole school of singers that included June Christy and Chris Connor. Drug arrests and a 14-year heroin habit would dog this legendary jazz vocalist and take her off the scene for most of the 1960s; but she kicked her habit, overcame her personal struggles, and lived to tell about it all in her 1981 memoir High Times, Hard Times. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll delve into the music of her early years, when the big band era was at its height, and we‘ll hear some comments from O‘Day herself, taken from an interview that I did with her in 2003.

Anita O‘Day was born in Kansas City, Missouri on October 18, 1919. Her actual surname was Colton, and she later changed it to O‘Day because it was the pig Latin version of dough, and, as she said, she "wanted to make some." When she was a child her parents moved to Chicago; shortly after that, her father walked out, leaving Anita alone with her mother. Their only bond, she wrote in High Times, Hard Times, was music.

During the Depression in the 1930s, O‘Day became a professional Walkathon contestant. She once spent nine days in a row chained to the same partner. During these grueling spectacles she also sometimes sang as part of the evening‘s entertainment. One of the songs O‘Day performed was "The Lady in Red." Here‘s a recording of it that she did years later with the Stan Kenton Orchestra in 1944:

During this period Anita O‘Day enjoyed her first brush with fame and notoriety. A friend had warned her to avoid involvement with her dance partner, and she heeded his advice. Weeks later, she awoke to find a picture of her and her former partner on the front of the newspaper. The partner and his female companion had been shot to death by the companion‘s irate husband. The caption read, "The girl in the photo has no connection with the tragedy."

Around this time an even more significant event occurred. Near the end of a dance-a-thon, exhausted and still on her feet, O‘Day had a vision. Suddenly, she wrote in her memoir, she was walking alone, and a man with white clothes, shoulder-length hair, and a beard appeared to her. "In my mind," she said, "there was no doubt that he was Jesus." "What are you going to do in this world, Anita?" he asked her. "What is it you‘d like to do?" She replied: "If I had my wish, there is only one thing I‘d like to do: sing." "You‘ve got it," he answered. "That will be it."

In the next several years O‘Day became a part of a more secular world, Chicago‘s Uptown club scene, singing and working with some intriguing hipster acquaintances, such as hipster comedian Lord Buckley. But the Uptown scene started to fade. O‘Day married a musical ascetic named Don Carter, but the marriage didn‘t work out. One night a Downbeat editor who was opening a new jazz club in Chicago‘s Loop approached her; he wanted her to be his house singer, but first he needed to know if she could sing "I Can‘t Get Started." After she sang it, he gave her a twenty-dollar tip and the job that would put her in the limelight.

Performing at the new club, she got written up in Downbeat. Gene Krupa, the drummer who led a popular big band, had caught her act and told her he wanted her if his current singer ever moved on. She began a new romance with a golf professional named Carl Hoff--and in 1941, when Gene Krupa came calling again, she was ready. O‘Day made her debut with the Krupa band at the University of Michigan on Valentine‘s Day 1941. Her only number that night was "Georgia On My Mind." Shortly afterwards she went into the studio for the first time and recorded the song with Gene Krupa:

O‘Day stood out from the other big-band women singers of the time, or canaries, as they were called. She carried her own luggage and wore a short skirt and band-jacket instead of the glamour-gowns that most bandleaders insisted upon for their vocalists. She acted so independently of social mores that some questioned her sexual orientation. As the Hollywood Note would say of her in 1946, "Anita O‘Day is completely frank. She says what she thinks, wears what she pleases, behaves as she prefers to behave." Her approach challenged big-band notions of gender. O‘Day wasn‘t pursuing an agenda, though; she was simply being herself.

Another musician had joined Gene Krupa‘s band as well: trumpeter Roy Eldridge. In the age of segregation, hiring the African-American Eldridge as a featured soloist in a white band was a bold move. It also set the stage for O‘Day‘s first big hit, a song that featured her and Eldridge in playful repartee. "Let Me Off Uptown" made Anita O‘Day a star:

"Let Me Off Uptown" changed everything for O‘Day. People stopped her on the street, asked her to autography soggy napkins in bars. The record sold well over a hundred thousand copies, but O‘Day made only her standard recording fee from it: $7.50 a side. In addition to the uptempo, swinging numbers that she recorded with Krupa, she also did ballads. In late 1941 the Krupa band recorded Johnny Mercer and Hoagy Carmichael‘s song, "Skylark":

In 1942 O‘Day finished fourth in Downbeat‘s girl-singers poll, behind Helen O‘Connell, Helne Forrest, and Billie Holiday. The hits with Krupa kept coming--songs such as "Thanks for the Boogie Ride" and "Massachusetts"-- but the relentless, night-after-night pace of work on the road began to take its toll, and in December 1942 O‘Day left the band after a six-week stand at the Hollywood Palladium. In the summer of 1943 she married fiance and now-serviceman Carl Hoff and was getting ready to return to the Krupa band when its leader was arrested for marijuana possession. Krupa‘s subsequent jail term, the American Federation of Musicians‘ recording ban, and O‘Day‘s life as a war bride took her briefly out of the spotlight, even though she remained popular in magazine polls. She did a brief stint with Woody Herman‘s big band. In the spring of 1944, at the behest of her husband and her manager, she joined a group that pursued a sound far different from that of Krupa‘s: the Stan Kenton Orchestra. At her very first commercial session with Kenton, she gave him a huge hit, much as she‘d done with Krupa: "And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine":

Although Stan Kenton‘s style was at odds with O‘Day‘s, she later wrote that her time with the Kenton band helped nurture and cultivate her innate sense of chord structure. When she finally decided to leave him in 1945, she found a singer in a Chicago nightclub who sounded quite similar to her. The girl‘s name was Shirley Luster; after she replaced O‘Day in Kenton‘s band, she became June Christy. O‘Day‘s style had evolved in part from a childhood accident in which a doctor accidentally sliced off her uvula while removing her tonsil, leaving her unable to vibrate sound in that part of her throat. As a result O‘Day tended to favor eighth and sixteenth notes; "Whether June Christy and Chris Connor had the same doctor and lost their uvulas too I don‘t know," she wrote in her memoir, "but they push that tone forward."

O‘Day‘s appreciation for jazz musicians and her close listening to their approaches on their instruments also had a strong influence on her unique vocal style. As songwriter Johnny Mandel once said of her, "She was an original, and there‘s very few of them in this life. Nobody sang like that before her, but a lot of people tried to sing like her after that."

Around this time O‘Day began to pursue small-group work. She made her first recordings as a leader for Capitol in 1945; the records remained unreleased for more than 20 years, however, after Capitol founder Dave Dexter became angry with her for signing up once again with the newly-reformed Gene Krupa band. Here‘s "Them There Eyes" from that session, a song that was a staple of O‘Day favorite Billie Holiday:

O‘Day also did a radio-transcription session with the Nat King Cole Trio in 1945 that included the only song she knew when she began singing in Chicago in the 1930s… "I Can‘t Give You Anything But Love":

O‘Day‘s 1945 tour of duty with the Krupa band produced more hits for him, including the song that began this program, "Opus 1." But the pressures of big-band life, with its endless gigs and traveling, began to get to O‘Day again. One night she failed to show for a radio gig and retreated into a bedroom closet of the residence that she shared with her husband Carl Hoff. Although her emotional collapse lasted for only six weeks, she wrote in her memoir that the year of 1946 was like a blurred dream to her. In 1947 she signed with Bob Thiele‘s Signature label and began to make records that were tinged with the influence of the new sound in jazz: bebop.

In the late 1940s Anita O‘Day suffered her first drug bust, arrested along with her husband Carl. "No one can know what humiliation is until he‘s been handcuffed, shoved into a police car, and hustled down to jail," she wrote in High Times Hard Times. Both were convicted, lost their appeals, and ended up serving 90-day jail sentences. During the legal proceedings O‘Day also divorced her husband. These events furthered O‘Day‘s already-established reputation as a free spirit, which would lead to her being billed as "the Jezebel of Jazz."

The turmoil of O‘Day‘s personal life coincided with upheaval in the jazz world. In the fall of 1948, O‘Day got a chance to perform with another of her musical favorites, Count Basie, at the Royal Roost in New York City. The band performing opposite Basie was Miles Davis‘ Birth of the Cool nonet. New styles and sounds were in vogue, along with a new drug: heroin. O‘Day observed musicians such as Charlie Parker and Fats Navarro sitting upright but apparently asleep; she attributed their state to the exhaustion of playing so much. Mostly, though, she was just thrilled to be singing with Count Basie:

Although O‘Day had already started out on her own path as the big band era began to fade, the end of the decade would prove challenging as she and other vocalists tried to score chart success with commercial and novelty-minded songs that didn‘t always suit the deliverer. It was a frustrating time for O‘Day; in a July 1950 DownBeat article titled "I Want To Create My Own Music" she wrote, "Voices can be used as instruments. Beethoven proved this long ago when he wrote his "Ninth Symphony," but there are very few people orchestrating for voices today. The opportunities for a singer, like myself, who wants most of all to be a musician, are few. Working with a small group is one of the ways a contemporary singer can get the chance to experiment with her voice."

For O‘Day, the opportunity she sought was just around the corner; in 1952 jazz impresario Norman Granz would sign her to his Clef label, and she‘d begin a ten-year run of recordings that showcased her in both small-group and larger-ensemble settings, gave her a stronger hand in selecting material and how it was presented, and ensured her legacy as one of the 20th century‘s most notable jazz singers. In 1958, she‘d gain further renown with her rendition of "Tea For Two" at the Newport Jazz Festival, immortalized in the movie Jazz On A Summer's Day. Here‘s her recording of the song with Gene Krupa in 1945, during the decade that set her on her way to becoming a jazz legend:

(With much gratitude to the late Ms. O'Day for the 2003 telephone interview that was excerpted in this program):