Welcome to Night Lights… I’m David Brent Johnson. In 1962 pianist Ahmad Jamal, whose trio had achieved both commercial success and artistic influence from the mid-1950s on, broke up that group and took a breather from the music business. By 1966 he had a new trio in place that would reach its zenith in the next several years as Jamal’s spacious and evocative sound evolved and he drew on new repertoire by composers such as Herbie Hancock and Antonio Carlos Jobim. In the next hour we’ll hear some of the recordings that they made between 1968 and 1971 for the Impulse label. It’s “The Second Great Trio: Ahmad Jamal On Impulse”… coming up on this edition of Night Lights.

Ahmad Jamal, “Dolphin Dance” from Freeflight (4:51)

Pianist Ahmad Jamal performing Herbie Hancock’s “Dolphin Dance” in 1971 at the Montreux Jazz Festival, with Jamil Suliemann Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums… that comes from Jamal’s Impulse album FREEFLIGHT.

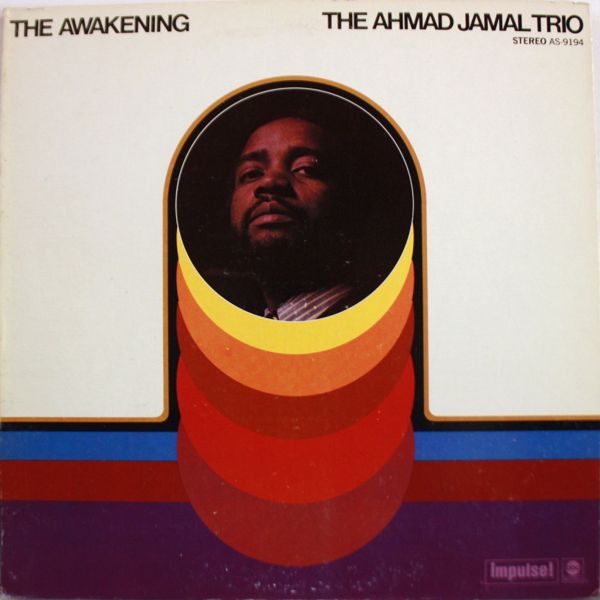

Segment 3: music bed—“The Awakening”

Pianist Ahmad Jamal’s jazz legacy finds its earliest foundation in the run of recordings that he made between 1956 and 1962 with bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernal Fournier, which produced the best-selling 1958 album BUT NOT FOR ME and also won the well-publicized admiration of Miles Davis, who was influenced by the pianist’s use of space and even told his own pianist at the time, Red Garland, to play more like Jamal. But there is a second trio in the Ahmad Jamal story, together from 1966 to 1973, that eventually produced a series of albums for the Impulse label that represent another highwater mark in Jamal’s lengthy career. In his book THE HOUSE THAT TRANE BUILT: THE STORY OF IMPULSE RECORDS, Ashley Kahn writes that “The Impulse titles caught Jamal in stylistic transition, fusing his signature characteristics of the Fifties—elegance, economy, and shifting rhythms—with more contemporary approaches to jazz piano, and choosing more up-to-date material, like tunes composed by McCoy Tyner and Herbie Hancock.”

Ahmad Jamal was born in Pittsburgh on July 2, 1930, a city that has produced other jazz piano greats such as Earl Hines, Mary Lou Williams, Billy Strayhorn, and Erroll Garner. By his early teens he was playing piano professionally and winning the praise of jazz piano giant Art Tatum, who identified Jamal as “a coming great.” At the beginning of the 1950s he converted to Islam and changed his birth name, and also made his first recordings as a leader, in a piano-bass-guitar format similar to that of the popular Nat King Cole trio. By 1957 he was working with bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernal Fournier, and it was this group that made the iconic live album AT THE PERSHING: BUT NOT FOR ME. Never fond of touring, Jamal drew on his success to open his own restaurant and club at which he could perform in Chicago, called the Alhambra. But the stress of being a business owner as well as a performer took a toll, and in 1962 Jamal closed the club, disbanded his trio, and took a break from the music business. He also harbored aspirations of studying at Julliard, but by the end of 1964 he was once again recording and putting together a new trio. Just as Miles Davis had his so-called “Second Great Quintet,” the Jamal working group of 1966-1973, with Jamil Suliemann Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums, might be labeled the pianist’s “Second Great Trio.” Their earliest records for Cadet give some hints of what was to come, but they didn’t fully hit their stride until Jamal began to record for ABC and its jazz label Impulse in 1968. We’ll start off music from their album TRANQUILITY, including the title track and Jamal’s rich interpretation of a Burt Bacharach-Hal David tune that would find favor with Rahsaan Roland Kirk as well. Here’s Ahmad Jamal and “I Say A Little Prayer,” on Night Lights:

Ahmad Jamal, “I Say A Little Prayer” (2:31)

Ahmad Jamal, “Tranquility” (8:55) (total time: 11:21)

Pianist Ahmad Jamal performing his composition “Tranquility” from his 1968 album of the same name, with Jamil Suliemann Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums. From the same album we also heard the trio performing Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s “I Say A Little Prayer”.

Jamal’s next album documented the trio with Nasser and Gant in performance at the Village Gate in New York City. Around this time the pianist was focusing much of his energy on launching three different labels of his own. “During that period with ABC/Impulse, I wasn’t interested in too much except trying to run my own record company and stay off the road,” he later told jazz writer Ashley Kahn. But the Impulse contract enabled Jamal to raise needed funds for his business ventures. His reluctance to go into the studio may explain why three of his five albums for the label were live recordings. On these albums he also expanded his repertoire, tapping pop hits of the day as while as recent jazz compositions by artists such as Herbie Hancock and Oliver Nelson. Whatever the material, it underwent an orchestral-like transformation at the hands of the pianist. Saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, like Miles Davis a fan of Jamal, said, “Ahmad’s not like the average jazz musician who uses the pop tune as a vehicle. He approaches each number as a composition in itself, and tries to work out something particular for each tune that will fit it.” Among the tunes Jamal worked his magic on during the Impulse era were two by bossa-nova songsmith Antonio Carlos Jobim. We’ll hear both of them in this next set, starting with “How Insensitive,” on Night Lights:

Ahmad Jamal, “How Insensitive” (5:50)

Ahmad Jamal, “Wave” (4:26) (total time: 10:16)

Pianist Ahmad Jamal performing Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Wave,” with Jamil Suliemann Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums, from the 1970 album THE AWAKENING. Before that we heard the trio doing Jobim’s “How Insensitive,” recorded live at New York City’s Village Gate in 1969, from the Impulse album POINCIANA REVISITED. I’ll have more of the music of Ahmad Jamal in just a few moments. You can hear many previous Night Lights programs on our website at wfiu.org/nightlights. Production support for Night Lights comes from Columbus Visitor's Center, celebrating EVERYWHERE ART AND UNEXPECTED ARCHITECTURE in Columbus, Indiana. Modern architecture and design to explore forty-five minutes south of Indianapolis. More at Columbus dot I-N dot U-S. I’m David Brent Johnson, and you’re listening to “The Second Great Trio: Ahmad Jamal On Impulse,” on Night Lights.

Ahmad Jamal, “Manhattan Reflections” (studio) (1:00)

I’m featuring music from pianist Ahmad Jamal’s trio of the late 1960s and early 70s on this edition of Night Lights. In the early 1960s Jamal had disbanded his earlier, highly-successful trio and withdrawn from the music scene for a couple of years, only to return with a new trio that by 1966 included Jamil Suliemann Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums. This second trio has been overshadowed by its predecessor, in part perhaps because none of the albums it recorded achieved the marketplace success of the live recordings Jamal made in 1958. But the albums the second trio made for ABC and Impulse between 1968 and 1971 are dynamic outings that reflect a bolder, more overtly powerful direction in Jamal’s playing. In a reissue of the Impulse recordings Bob Blumenthal described Jamal’s work from this era as “more assertive, more inquisitive, more demanding upon the listener; it developed that edge that I hear in the music of all of the inspired jazzmen.” At the same time the conversational rapport of the earlier trio found a new form with Nasser and Gant, heard best on the 1970 LP THE AWAKENING, an album that can be bookended with Jamal’s iconic BUT NOT FOR ME as another masterpiece. In his liner notes to the album critic Leonard Feather extolled the “extraordinary empathy” of the trio, particularly on its performance of Jamal’s composition “Patterns.” “Notice particularly how superbly Nasser’s bass lines are coordinated with Jamal’s left hand when the arrangement calls for it,” Feather wrote. “At other points, Jamal plays incredibly delicate single-note right hand lines while using the left for punctuation, leaving the underlying pulsation to Nasser and to the sturdy eight-beat sticks-on-cymbal of Gant.” Jazz critic and Impulse chronicler Ashley Kahn singles out another track, “Stolen Moments,” for how Jamal “maintains the cool mystery at the opening of Oliver Nelson’s signature tune, then restructures it, section by section, mood by mood.” We’ll hear both recordings now, beginning with “Patterns”…. Ahmad Jamal on Night Lights:

Ahmad Jamal, “Patterns” (6:19)

Ahmad Jamal, “Stolen Moments” (6:27) (total time: 12:41)

Ahmad Jamal performing Oliver Nelson’s “Stolen Moments,” and his own composition “Patterns” before that, with Jamil Suliemann Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums, from Jamal’s 1970 Impulse album THE AWAKENING.

During his time at Impulse Jamal began to experiment with playing electric piano, a development that he said came about after a Steinway piano failed to be delivered in time for a recording session, prompting Jamal to begin using an electric piano that was available in the studio. Jamal played an electric piano with increasing frequency after he stopped recording for Impulse and took up with the 20th Century Fox label for the rest of the 1970s. Perhaps, as musician Jim Sangrey notes, Jamal’s embrace of the Fender Rhodes resulted in a critical and public shying away from this era in general. Although a 2-LP anthology drawn from his Impulse recordings was issued in 1974, and THE AWAKENING is frequently cited as a jazz piano touchstone, this period of Jamal’s storied career continues to linger in the shadow of his first great trio of the late 1950s and early 60s. I’ll close with Jamal’s 1971 revisitation of one of his most popular jazz interpretations which had helped propel the success of the 1958 Pershing album—Ahmad Jamal and “Poinciana,” on Night Lights:

Ahmad Jamal, “Poinciana” (11:20)

I closed with Ahmad Jamal performing “Poinciana” live at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1971, with Jamil Suliemann Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums, from the Impulse album FREEFLIGHT. Thanks for tuning into this edition of Night Lights. Special thanks to Jim Sangrey and other members of the Organissimo jazz discussion forum and to Ethan Iverson. You can hear many previous Night Lights programs on our website at wfiu.org/nightlights. Production support for Night Lights comes from Columbus Visitor's Center, celebrating EVERYWHERE ART AND UNEXPECTED ARCHITECTURE in Columbus, Indiana. Modern architecture and design to explore forty-five minutes south of Indianapolis. More at Columbus dot I-N dot U-S. Night Lights is a production of WFIU and part of the educational mission of Indiana University. I’m David Brent Johnson, wishing you good listening for the week ahead.