"I Just Saw Michael Stipe In Bloomingfoods!"

Imagine that it‘s 1966, and you‘ve just been told that the Beatles are coming to Bloomington to record their next album, or that Bob Dylan will be setting up camp in this small Midwestern university town to lay down his next masterpiece. For one generation of young Bloomingtonians, this sort of story came to pass in the spring of 1986, when the rock band R.E.M. walked among us for a few weeks as they produced Lifes Rich Pageant, the album that served as a bridge for the band‘s journey from college-radio icons to top 40 superstars. In doing so, they also left an indelible stamp on a number of students and town residents who encountered them-people who went on to become artists, business owners, professional musicians, and music promoters, all inspired by a rock band‘s example of aesthetic dedication, independence, and integrity.

I was a 20-year-old English major, at the zenith of my R.E.M. fandom, when a friend in my creative writing class casually informed me of the word-of-mouth news. (There was, of course, no Twitter, no Facebook, no email or cellphone way of distributing this information in 1986, and so people around town learned of it only gradually.) I went home and told my girlfriend that I‘d just heard that R.E.M., the ultimate purveyors of Southern-mystic pop, would soon be arriving in town to make a new record.

My girlfriend was unimpressed. "So what?" she said, blowing smoke out an open window beside the stairs. It was April, and we could feel the air on our arms again. "They're just people, for God's sake."

Three days later she came charging up the stairs and burst into my apartment. "Brent! Brent! I just saw Michael Stipe in Bloomingfoods!" she gasped. She had the awe of one who'd looked up to see Jesus browsing through the bulk goods.

A Call To Arms For A New Musical Counterculture

The first time I saw anybody from R.E.M. was in concert at the IU Auditorium in November 1985, just a few months before their extended visit to make an album in Bloomington. The darkened stage featured a gothic Southern mansion backdrop. A train light and whistle preceded the band members‘ entrance, and when lead singer Michael Stipe walked out, a silhouetted profile with a beret on his head turning to look at us while the opening three-note guitar figure of "Feeling Gravitys Pull" chimed like the tolling of a surrealistic clock, it seemed as if a spellbinding underground religious ceremony had begun.

Such was the mystical, celebratory power of R.E.M. for college students in the mid-1980s. By then R.E.M. was well past their peak of being hip (circa 1982-84); those who were truly cool had Sonic Youth and the Jesus and Mary Chain on their turntables now. Somewhere, though, in the great mid-80's divide between the Grateful Dead and Joy Division, R.E.M. captured and compelled a large, fanatical audience, who listened to their albums over and over, hypnotized by guitarist Peter Buck's sparkly arpeggios and Michael Stipe's slurred and mumbled, Finnegans-Wake-by-way-of-Faulkner lyrics and vocal delivery. What the hell was he saying? It must be profound. It was profound, in the sense that people came up with all sorts of interpretations that said far more about them than Michael Stipe. No wonder some scoffed that the band's name stood for Remedial English Majors.

By the time R.E.M. disbanded in amiable fashion in 2011, they had built a legacy of fifteen full-length albums, a clutch of worldwide hits such as "Stand" and "Losing My Religion," and a genre they had practically invented: alternative rock, a category scarcely imaginable when the band formed in Athens, Georgia in 1980. Guitarist Peter Buck once described their music as "the acceptable edge of the unacceptable stuff." Their debut 1981 single "Radio Free Europe," powered by what critic and former IU grad student Anthony DeCurtis describes as "all the energy of punk, but imbued with an incredible optimism," had been a call to arms for a new musical counterculture, fulfilled by the band‘s subsequent LPs Murmur, Reckoning, and Fables Of The Reconstruction.

"That R.E.M. would play an essential role in energizing a new network of underground college radio stations that was supportive of local music and open to new sounds from everywhere was just one of the band‘s foremost contributions to the music scene of its day," says DeCurtis. "Fans had heard their own ‘Radio Free Europe‘ – a blast of revolutionary fervor broadcast behind enemy lines to rally a previously dormant population."

"Those were dark years on the radio, as far as I was concerned," says Jeanne-Marie Grenier, an IU fine-arts major at the time of R.E.M.‘s Bloomington sojourn. "It was the Huey Lewis era. R.E.M. was intellectual, referential and romantic."

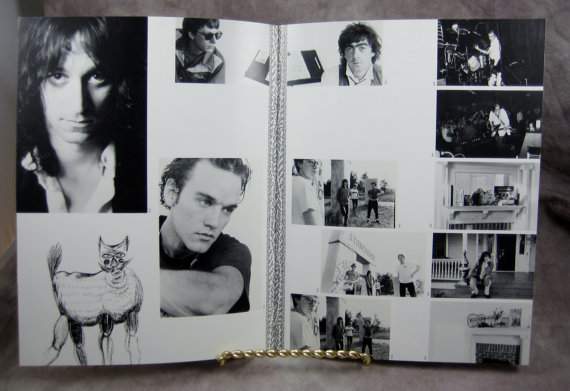

"In Reagan‘s America, R.E.M. were alternative before alternative was born, and for closeted art students, anti-jocks, upper middle class white kids who couldn‘t get into metal because it was too low-class and low-brow, and other outsiders, R.E.M. somehow seemed to open a door to a new way to be," says Lawrence Wells, another fine-arts student at Indiana University when the band came through town in 1986. "They were literary and good looking. Stipe had a magnetic presence, his smooth moonface with thick James-Dean lips framed by those Roger Daltrey curls; he almost looked like a young Elvis Presley if you look at the early interviews on youtube."

The private and passionate aesthetic that R.E.M.‘s music promoted in those years could provoke responses that at times bordered dangerously on solipsism; a fellow fan once told me of going into a room at a party and finding its occupant writhing ecstatically on the bed, all alone, as he listened to the band. It was like a couple of steady drinkers at the Video Saloon talking about some poor sap that got hauled off to rehab. What a loser! But we felt too close to it, to the spell of time-tinged dreams and memories that R.E.M. evoked so adroitly on their early records.

"Their music was the smell of mothballs on old sweaters, front porches at night, lightning bugs in your backyard, and all of the things at your grandmother's house," says Pete Smith, a passionate R.E.M. fan who was working as a cook at the Daily Grind Coffeehouse in Dunnkirk Square during the band‘s springtime stay, and who would go on to buy and operate two landmark downtown cafes in later years before retiring to become a stay-at-home father. "Ray Bradbury meets Carson McCullers, a real magical childhood vibe."

"If You Have Things To Say, Now's The Time To Say It"

Lee Williams, the Bloomington music promoter who founded the Lotus World Music Festival in 1993, now a linchpin of world music culture, was another resident who became a devoted follower of R.E.M. in their up-and-coming years. He was instrumental in forging the band‘s early connection to Bloomington, bringing them here for shows at Second Story in November 1982 and Jake‘s the following spring.

"I think I paid them $350 to play Second Story," he recalls. "I just loved the guitar work, and Michael Stipe‘s voice, and the whole college-rock thing. I was 24 years old and I was living a dream; I‘d never imagined that I could book bands. I kind of bonded with Michael a little; I think he sensed my love for my music. The show was fantastic, it sold out. Everybody was dancing, Michael Stipe was dancing more than you‘d see him later in their career when they got famous. At the very end, on the encore, he brought me up on stage and I got to dance with R.E.M. My favorite memory of the Jakes show was Michael Stipe dedicating a song to me from the stage during the performance--‘Talk About the Passion.‘ I think that song resonated for me, it sounded like he recognized someone who loved the music and had it in his blood and treated the artists well. There‘s no other band for me with personal highlights for me from two different shows."

Why did R.E.M. come back to Bloomington three years later to record their fourth full-length record? They wanted to make an album with Bloomington-based superstar John Mellencamp‘s producer, Don Gehman--a move that caught many of their college-rock-base fans off-guard. "We had just worked with Joe Boyd on Fables of the Reconstruction in London, and it was a tough experience for us," says Mike Mills, the band‘s bassist. "We wanted to get away from the sort of murky feelings and sounds that we got out of Joe in London. The acoustic guitars sounded so good on the Mellencamp records… we just liked that sonic quality that he had, and we decided to give Don Gehman a shot. He really knew how to get a lot of detail and subtle quality and at the same time make it rock."

The band worked at Mellencamp‘s Belmont Mall recording studio a few miles east of Bloomington, and the subsequent album, Lifes Rich Pageant, was only the second record to be made there. (Mellencamp‘s 1985 release Scarecrow was the first.) "The studio itself, the recording space, was larger than what we were used to," says Mills. "It was newer, the technology was more contemporary. Don Gehman of course knew it well, and it had everything he needed, so if the producer‘s comfortable, that helps a lot. But we managed to get a lot of good sounds out of there." One such sound was that of an old pump-organ retrieved from a nearby barn--one of several organic touches added to an album dominated by dynamic guitar textures, an amplified drum presence, and the most surprising new phenomenon of all: relatively intelligible vocals from lead singer Michael Stipe.

"Don really pushed Michael very hard lyrically," says Mills. "He challenged Michael to sing a little more clearly, cause he said I‘m going to turn you up louder, you‘re going to be up more in the mix… if you have things to say, now‘s the time to say it."

What did Mellencamp himself think of the band? Mills, who professes friendship with Mellencamp today, says R.E.M. did not encounter him much during their stay, although he was in town to play a concert at Memorial Stadium for Little 500 weekend. "It was good of him to let some wonky band he probably didn‘t know about come in and use his studio."

Of Taxis, Tribes, And Pith Helmets

As work on Lifes Rich Pageant progressed, band members became a highly visible presence around town, often eating at the Runcible Spoon in the morning before heading out to work at Belmont Studio and hitting the downtown bars at night. On Sunday, April 20, the very first CultureShock, a sort of campus-alternative-Woodstock event, took place in Dunn Meadow, and Michael Stipe showed up at it. He wandered among the tie-dyed hippies and goth-black punks wearing a brown wool suit and cap, looking unseasonably dressed and rather weathered for his age of 26. People besieged him, asking him to sign petitions, asking him about his lyrics, asking him if the band was going to play later that day, until he finally took refuge behind a billboard. There my girlfriend who'd seen him in Bloomingfoods engaged him in a discussion about how tasty the co-op's deli offerings were. When he saw her again at a party later that night, he said, "Thanks, that was the only intelligent conversation I had all day long."

In spite of such incidents of Michaelmania, the band‘s encounters with students and town residents were, by all parties‘ accounts, almost overwhelmingly positive. "In my experience as a woman playing music, Peter was one of the few guitarists who bothered to teach me anything," says Hilary McDaniel Douglas, who spent time with Buck and other members of the band during their Bloomington stay. "We used to sit around and jam. Peter would play with anyone and record with anyone, but we spent hours noodling. We both had a passion for country blues like Charlie Patton, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Peetie Wheatstraw. I believe all of them actively wanted to help local music and absorb local tastes."

That certainly proved true for musician James Combs, who would go on to form the successful Bloomington indie-rock group Arson Garden, and artist Lawrence Wells, who played in a band with Combs called the Figments. Michael Stipe came to see them play at Second Story on Friday, April 25, and Peter Buck sat in on a recording session with them.

"I always felt we kind of learned the secret of their success when they came and spent time in Bloomington," says Combs, now a professional composer and musician who lives in Los Angeles. "They went everywhere, they saw every band and most of the time said something nice about your performance, they hung out with everyone… They could have just stayed holed up out in the studio, but they were curious and friendly and engaged with our town-and really nice people, too-smart and down to earth. They seemed to like Bloomington, and Bloomington loved them in return "

Fellow Figments member Wells, who now lives in the Czech Republic where he works as an artist and English instructor, got to spend some time with Michael Stipe. "I was walking down the street with my friend Karen when Stipe drove by in his taxi and stopped because he knew Karen," Wells remembers. "He invited us to their condo to watch a video. Karen declined but I jumped into the back of the cab. So I hung out there with R.E.M, tried on Stipe‘s glasses in the bathroom, and that inspired me to write this song ‘Wearing Your Glasses‘ for the Figments,. Basically I was thinking the whole time what it must be like to be Michael Stipe; his job seemed to be being an interesting personality. He was my hero because he was a rock star and an artist. I also bumped into Stipe a few other times around the IU art department and exchanged a few words with him."

A small circle of young Bloomingtonians kept more constant company with Stipe and other members of the band, hanging out at the Daily Grind coffeehouse in Dunnkirk Square and going out to the quarries. Hilary McDaniel-Douglas, who‘s now the artistic director of the Project In Motion Aerial Dance Company, remembers "the Tribe," as she calls this group of people, helping to write lyrics on these occasions. A fellow "tribe" member's facsimile of a rough draft of the Declaration of Independence inspired the lines "Our fathers' fathers' fathers tried/erased the parts they didn't like" in "Cuyahoga"; he says, "Stipe was fascinated by it, particularly because you could see Jefferson's original words scratched out."

Another companion of Stipe‘s recalled singing songs from the album-in-progress with the vocalist while they drove around Bloomington in a black taxi that Stipe bought from Yellow Cab (Stipe had smuggled the tracks out of the studio). After R.E.M. left Bloomington, Stipe called his companion to tell him that the cab had been struck by lightning as Stipe drove it in the Georgia countryside. The story fit his haunted, charismatic-preacher personality that seemed reminiscent of a character from a Flannery O'Connor story.

There was one uncomfortable moment for Stipe when he went to see blues legends Buddy Guy and Junior Wells perform at Jake‘s. "Buddy had probably had a little too much to drink, and he started this rant about white blues guitarists taking all the licks from black guitarists," says Lee Williams, who was sitting with Stipe. "It was pretty harsh to listen to. And so Michael at some point said, ‘This is too much, I‘m out of here,‘ and just walked away. And that was the last time I saw Michael Stipe."

Mike Mills recalls a more amusing Bloomington bar-going experience: " Peter and I, we used to go around and catch all the bands we could. There were a lot of people doing cover songs. We saw three different bands in one night do ‘Jungle Love‘ by Steve Miller, and at least two of them were wearing pith helmets at the time. We were kind of impressed with that."

"It Reminds Me Of Home"

Bloomington‘s lovely springtime weather also figures in Mills‘ memory of the bands‘ stay-a dramatic contrast from the cold, wet conditions that had helped to make their London sojourn while recording Fables the year before such an unhappy experience. "We were comfortable in our surroundings; that leads to making a better record. Bloomington was a really cool town at the time; still is." (He recently dropped in to hear a Bloomington friend‘s band play at the local bar Serendipity, and expressed pleasant surprise when he learned that it was the same space-the former Second Story-where R.E.M. made its Bloomington debut in 1982.)

One reason the band felt at ease was Bloomington‘s similarity to their Athens, Georgia hometown, another university city. "That's one thing I liked about it here," Peter Buck told a Los Angeles Times writer in 1986 shortly after wrapping up the album. "It reminds me of home, but there are all the benefits of not being at home. The problem with trying to do any work at home is that you're so comfortable. . . . You wake up in your own home, have all your records handy, go to the same familiar restaurants-it's hard to get in the mood to work and feel creative. It's good to go away because you're a bit on the edge."

Lifes Rich Pageant came out near the end of the summer, its title taken from a Pink Panther movie that the band had rented from the Top Ten Video store on South Walnut Street. The album received what was by now the usual round of positive R.E.M. reviews. Anthony DeCurtis, writing in Rolling Stone, proclaimed that "For R.E.M., the underground ends here… (It) is the most outward-looking record R.E.M. has ever made, a worthy companion to R.E.M.'s bracing live shows and its earned status as a do-it-your-way model for young American bands…. Suffused with a love of nature and a desire for mankind's survival, the LP paints a swirling, impressionistic portrait of a country at the moral crossroads, at once imperiled by its own self-destructive impulses and poised for a hopeful new beginning."

The album featured moving, subtle protest songs like "Flowers of Guatemala" and "Fall On Me" (songs perhaps too subtle, as Stipe had to explain why they were protests), as well as charging, more overt anthems such as the melodic squall of "Begin the Begin" and "These Days." "I Believe" was a spirited romp of free-associative optimism, while "Swan Swan H" imparted the mood of a Civil-War folk dirge. An obscure bubblegum pop cover, "Superman," could also carry Nietzschean weight coming out of Stipe's mouth, while "Cuyahoga," a song about the polluted river in Ohio, began with the words, "Let's put our heads together, and start a new country up." Some thought a line like that stupid, but Stipe sounded as if he meant it. He sounded as if he meant everything that he sang.

R.E.M. played the IU Auditorium again that September, and Michael Stipe's sole stage allusion to his time in Bloomington was, well, Stipean: he took a drink from his glass of water and said simply, "PCBs" (an ongoing environmental issue in the city during the 1980s). "Fall On Me" was released as a single and managed to nose into the bottom ranks of the Hot 100, with an accompanying video that Stipe had shot at a Bloomington quarry, while the album rose all the way to number 21 on Billboard‘s album charts-the highest ranking yet for an R.E.M. LP-and became the band‘s first record to go gold, taking the band one step further towards mass popularity.

Heartened by Pageant‘s aesthetic and relative commercial success, the band very nearly came back to Bloomington the next year to record its followup, Document, hoping to work once more with Gehman at Belmont Studios. "The Bloomington session had gone so well," says Mills, "but in fact Don didn‘t see us as wanting to have hit records. We were more interested in making good records, good LPs. He wanted a band that was really ambitious, a band that wanted to be on the top 40. That was not us, so he moved on to something else."

Instead, R.E.M. decamped to Nashville, Tennessee with producer Scott Litt, and the resulting album generated the very thing Gehman thought the band was unlikely to create-a hit single, "The One I Love," which landed in Billboard‘s top 10, garnering extensive airplay and video rotation on MTV. Document became R.E.M.‘s first platinum album and landed them on the cover of Rolling Stone with the headline, "R.E.M.: America‘s Best Rock And Roll Band." The article proclaimed that R.E.M. had "graduated," and as the band began to play ever-larger venues for more mainstream audiences, their college-roots fans found the notion to be true.

Three decades later, Lifes Rich Pageant strikes me as R.E.M.'s last magical album, although some of the magic comes from knowing that they recorded it here. It has the sound and feel of a Bloomington spring, a sunny, introspective lyricism underpinned by a defiantly youthful vitality. It is R.E.M.'s most successful convergence of the public and the private, a shimmering testament to the beauty of life and the necessity of change. The message is both bright and dark, with warnings of all sorts embedded in the songs, and ultimately a celebration of art, history, passion, community, protest, and hope-all values that seem quintessentially Bloomingtonian.

"I think that album was special because it felt like it was something they had made for us, " says Pete Smith, "for everyone who lived in Bloomington, whether they had heard of them or not. It was like some sister city cultural exchange program love letter between Athens and us." Thirty years on, that love letter still reminds all of us-artists, business owners, parents, and citizens-to make an insurgency of our pageant, and a pageant of our insurgency. Life is rich indeed, once we learn how to live it.

-David Brent Johnson

(Special thanks to James Combs, Anthony DeCurtis, Jeanne-Marie Grenier, Steve Llewellyn, Hilary McDaniel-Douglas, Mike Mills, Kevin O'Neill, Pete Smith, Lawrence Wells, and Lee Williams.)

(Note: a different version of this article originally appeared in Bloom Magazine.)