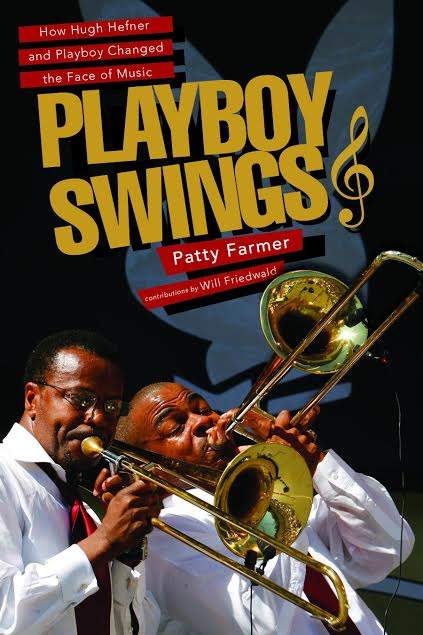

In 1953 a 27-year-old entrepreneur named Hugh Hefner launched Playboy Magazine, an early sign of the sea-change that would occur in sexual mores in the 1960s. Hefner was a passionate jazz fan, and through his magazine and its enterprises promoted jazz as a key aspect of a sophisticated lifestyle. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear some of the music associatd with his magazine and talk with Patty Farmer, author of Playboy Swings: How Hugh Hefner And Playboy Changed The Face Of Music, about the role of jazz in the Playboy entertainment empire.

The mid-1950s are often portrayed in American popular culture as a relatively quiet and staid time, the era of "Happy Days," President Eisenhower, and man-in-the-gray-flannel-suit conformity. But the dramatic changes that would come about in the 1960s were already getting underway, with the increase of civil-rights activism in the South, the sudden rise of rock ‘n roll singers such as Elvis Presley, and the appearance of Playboy, a new magazine started in Chicago by Hugh Hefner, a 27-year-old ex-copyrwriter and entrepreneur, that would help open the doors for the sexual revolution.

Playboy gained fame and a following for its portraits of attractive women wearing little or nothing at all, but it also served as a sort of ongoing handbook for male sophistication in the 1950s-and jazz was a key part of that sophistication. As Thomas Hine points out in his essay "Cold War Cool," jazz was undergoing a change of status in the mid-1950s, from the music of rebellion and bohemia to a music that could be listened to in one‘s suburban home on a high-fidelity music system. He also observes that Playboy was not without precedent in touting jazz connoisseurship as an emblem of suave masculinity; Esquire had done much the same in the 1940s. But Hugh Hefner took it to a new level with his own love of jazz and the opportunities afforded by the subsequent expansion of his entertainment empire.

Patty Farmer, author of Playboy Swings: How Hugh Hefner And Playboy Changed The Face Of Music notes that Hefner himself was a jazz fan, he would not have made jazz such a quintessential part of the 1950s Playboy experience if it hadn‘t resonated with his audience. Farmer says that the magazine's coverage of jazz inspired so much correspondence that Hefner began an annual jazz poll for subscribers. In 1959 the magazine's fifth-anniversary celebration also turned into a three-day jazz festival, including a number of renowned jazz artists such as Coleman Hawkins:

Though the festival was roundly considered a success, and the Playboy jazz polls continued apace throughout the 1960s, it would be 20 years before Playboy staged another festival. There was also a Playboy record label that issued licensed compilations of jazz, but in the wake of Hefner‘s devotion to the magazine and to the Playboy clubs that began to launch at the beginning of the 1960s, the label tended to receive little attention. Hefner also briefly plunged into the world of television, hosting a program called "Playboy‘s Penthouse" that featured a wide array of musical guests and entertainers, all relaxing on a stage-set presented as Hefner‘s apartment. Here‘s June Christy, briefly chatting with Hugh Hefner before doing one of her signature songs, on Night Lights:

Tony Bennett (a Playboy regular of sorts), Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, and Lambert, Hendricks and Ross were just some of the other jazz artists who appeared on Hefner‘s TV program "Playboy's Penthouse". Nat King Cole and comedian Lenny Bruce showed up as well, together in this 1959 clip:

Hefner's TV show didn't last long, in part because of his willingness to feature African-American artists such as Cole in integrated settings, though he'd revive the program several years later as "Playboy After Dark." But many jazz artists also appeared from the 1960s on in the clubs that Hefner opened around America and ultimately abroad. Here's some music recorded live at the Playboy Club in Chicago by pianist Harold Harris, "Hefner Just Walked In":

In 1962 Hefner decided to begin a high-profile interview feature in the magazine each month, and he started with one of the most significant jazz artists of the time: Miles Davis. "Hef could have chosen any sports star, any movie star, any politician," says Farmer, "and yet his commitment to jazz was such that he chose Miles Davis." (The interviewer was future Roots author Alex Haley

Though Hefner‘s passion for jazz continued unabated, he was open-minded about changing trends in music, and in the late 1960s and early 1970s non-jazz musicians began to appear in both the Playboy music polls and a brief revival of the television program, including artists such as the Grateful Dead and Deep Purple. The music poll ended in the mid-1970s, but several years later Hefner finally revived the Playboy Jazz Festival, bringing legendary jazz promoter George Wein aboard to run it. The festival featured both classic-jazz musicians such as Dexter Gordon and groups that reflected the musical fashions of the moment such as Weather Report, heard here performing their hit "Birdland" with Manhattan Transfer:

Though Playboy‘s jazz poll had faded in the 1970s, the Playboy Jazz Festival, which had been so successful in 1959, returned at the end of the decade and has been around ever since, putting it in the long-running company of other esteemed festivals such as Newport and Monterey. The festival is perhaps the most visible symbol of Hugh Hefner and Playboy Magazine‘s contributions to jazz over the past six decades. Patty Farmer says the two that she sees as most significant are "helping to break the color barrier-the 1959 festival was integrated on both the stage and in the audience, the clubs were integrated...and also just presenting jazz, making it a cool venue to sit and listen to... jazz had been primarily a dance music, but now jazz became something that you could put on a record player, mix a cocktail, and have a nice quiet evening with somebody that you cared about."

We close out this edition of Night Lights with early 1990s performances from the Playboy Jazz Festival by Tito Puente and Mel Torme.

Special thanks to Patty Farmer and Chris Parker.