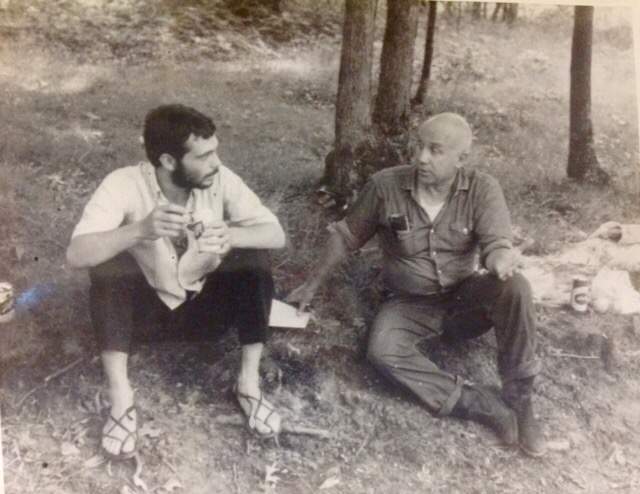

Jazz musician Dick Sisto and Thomas Merton in the late 1960s. (Photo courtesy of Dick Sisto)

The monk Thomas Merton became internationally renowned in the mid-20th-century for his writings about spirituality, but his love of jazz remains little known even today. On this edition of Night Lights we'll talk with jazz musician Dick Sisto, who was a friend of Merton's in the 1960s, and we'll also hear excerpts from experimental jazz meditations and reflections that Merton recorded in his hermitage in 1967, as well as some of the jazz that Merton enjoyed and referred to in his writings.

A Writer Turned Monk Turned Writer

When Pope Francis became the first Pope to address the United States Congress in 2015, he cited four individuals as what he called "representatives of the American people": president Abraham Lincoln, civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., social activist Dorothy Day, and a writer and monk named Thomas Merton. Merton, who led an artistic and bohemian lifestyle in his youth, joined a Trappist monastery in 1941 at the age of 26, and seven years later published a spiritual autobiography called The Seven Storey Mountain that became one of the most influential and best-selling religious books of the post-World War II era. In the 20 years that followed Merton wrote prolifically, struggled with personal and philosophical questions, taught younger monks planning to become priests, and spent the last three years of his life living in a hermitage before leaving for an extended tour of Asia, where he died at the age of 53 in December 1968. He remains one of the most influential spiritual writers of the past 100 years-and he was also a passionate jazz fan.

Merton was born in France in 1915, to parents who were artists, and who moved to New York City soon after his birth. Merton's mother died of cancer when he was only six, and his father passed away shortly before Merton's 16th birthday. He spent most of his adolescence in England, but after a short and unsuccessful stint at Clare College in Cambridge, he went back to America and enrolled at Columbia College, where his cultural passions took strongest hold in the Depression-era crucible of New York City, a place where jazz was thriving. In his writings he singles out some specific recordings to which he gravitated during this period, including Louis Armstrong's "Basin Street Blues" and Duke Ellington's "Echoes of the Jungle":

Merton was also a fan of the cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, who had died in 1931 at the age of 28 from alcoholism and pneumonia. His piano-piece "In A Mist" was one of Merton's favorites:

Merton would later look back on these years of his youth as a time when he himself was in a bit of a mist. He thrived on literature and art, enjoyed alcohol and the company of women, and pursued his ambition of becoming a writer. He formed lifelong friendships with Columbia professor Mark van Doren and poet Robert Lax. But he'd been experiencing spiritual stirrings off and on as well, and after converting to Catholicism, he eventually entered the Gethsemani monastery in rural Kentucky and became a Trappist monk—about as far away from the jazz-driven world of New York City as one could imagine. He also thought that he was leaving behind his ambition to become a writer. But Merton's abbott encouraged him to write, and when his memoir of his path to becoming a monk, The Seven Storey Mountain, was published in 1948, it became an unexpected bestseller. In the years following the brutal period of World War II it seemed to speak to many people who felt a spiritual longing, and the book even inspired a number of them to move into monasteries themselves.

For the next 20 years Merton would experience a series of ups and downs as he continued a prolific pace of writing while maintaining his various duties as a monk. Removed from the world he had once inhabited, he usually felt a great sense of peace, and after his occasional forays back into it, he would express regret; a journal passage from 1960 castigates himself for sitting around listening to jazz at a friend's house. As the 1960s progressed, however, Merton began turning back towards the world in a variety of ways, and making new friends. One such friend was jazz vibraphonist Dick Sisto.

Sisto was 25 when he met Merton on the Louisville jazz scene in the late 1960s. Merton sometimes had to travel to Louisville, about an hour's drive from the monastery, for doctor visits and other errands, and he often took advantage of these opportunities to meet with friends and go hear jazz, especially at Eddie's on 118 S. Washington Street-the address used for the Louisville Jazz Council (forerunner to today's Louisville Jazz Society) that Merton had formed in 1965 with, among others, future NEA Jazz Master Jamey Aebersold. Sisto was already aware of Merton's presence in the area, and became friends with the monk and writer through their mutual interest in Zen and jazz, eventually visiting him at the monastery and at his hermitage. He found in Merton an artistic kindred spirit and a source of inspiration.

Merton seemed to sense in jazz the same thing he sought in his relationship with a spiritual power: the ability to lose oneself, and through so doing, find oneself as well. In his memoir Song For Nobody Merton's friend Ron Seitz described their visit to Eddie's in early 1968, on a night when saxophonist Eddie Harris's quartet was performing. Merton was particularly impressed by the bassist, Melvin Jackson. Seitz wrote that Merton "became the music. He became the calloused thumbs of the bass player…urging the bassman on to new highs with 'Give it! Here! Take it!'" Here's a studio recording of the group from around that time, performing "Listen Here":

In his journal Merton wrote of speaking with the group's bassist, Melvin Jackson, calling him "a really dedicated artist" and describing how the music they played had "power and unity and drive… It was very fine, very real." Dick Sisto says Merton comprehended jazz in the most basic and profound way: "Merton writes about it beautifully in The Other Side Of The Mountain... he got it."

Live performances were not the only way Merton was encountering jazz. In the late 1960s he was living in a hermitage on the Gethsemani property, the fulfillment of a decades-long desire for solitude. Still, he had frequent visitors, and he also had a phonograph player, which he used to listen to jazz, as well as the records of Bob Dylan and other contemporary folk and rock artists. He also had a tape recorder, and in 1967 he made an extraordinary recording of himself doing what he called a "jazz meditation" while he listened to Jimmy Smith's "Hoochie Coochie Man" and "Got My Mojo Workin'" while interjecting commentary that invoked the black-power spirit of the times and reading passages from Jeremiah 31 in the Bible.

Merton made his jazz-meditation recordings at the hermitage in 1967, a time when civil rights was at the forefront of American culture, and the avant-garde had assumed critical prominence in the jazz world. Merton was open to these sounds; in a letter to a friend's son he mentioned his admiration for contemporary saxophonists Ornette Coleman and Jackie McLean, although he added that "I am still more inclined to the old jazz of my own day-not because it is better but because I hear it better." Merton's friend Ron Seitz recounts visiting Merton at the hermitage and being driven to unpleasant distraction as Merton played John Coltrane's experimental Om on his record player-the one material indulgence that Merton allowed himself in the hermitage:

In 1968 Merton purchased Bob Dylan's latest LP, John Wesley Harding, and John Coltrane's expanded-ensemble free-jazz album Ascension on the same day. In his journal Merton describes listening to Ascension as "shattering… a fantastic, prophetic piece of music."

Merton had ushered in 1968 with what he called "a New Year's Eve" party for himself at the hermitage, once again using a tape recorder to document his thoughts while listening to jazz. He played records by Mary Lou Williams and Wes Montgomery, commenting on his love of Kansas City style jazz and expressing his hopes for the year to come. What 1968 would bring would be a string of losses: Montgomery himself, dead at the age of 45 from a heart attack, and Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, two of America's most significant cultural and political leaders, shot down by assassins. It became what Merton termed "a beast of a year." That summer, as he prepared to embark on what was planned to be a six-month journey to Asia, he gave his record collection, described as "mostly jazz," to his friend Ron Seitz. Merton left Gethsemani in September, traveling first to the West Coast, and then to Asia, where he spent time with the Dalai Lama and other spiritual personalities who shed new light on Merton's ceaseless search for greater understanding of what it is to be human and to be spiritual, and how to live one's life accordingly.

On December 10, 1968, after giving a lecture in Bangkok, Merton died in a freak accident in his hotel room, electrocuted by a defective fan after getting out of the shower. It was 27 years to the day after he had entered the monastery at Gethsemani. His friends were shocked by the profound loss, and many of them, Dick Sisto among them, have spent the subsequent decades celebrating and extending his legacy, embodied most directly in the great wealth of writings that he left behind. Like one of his favorite jazz artists, John Coltrane, Merton was always searching; when he first came to Gethsemani, he thought that he was abandoning writing to fully embrace God. Instead, he found, within that embrace, the heart of his vocation.

God Is In The House, On Night Lights

Also check out Tim English's Popology: The Music Of The Era In The Lives Of Four Icons Of The 1960s, which plumbs writings by and about Merton to detail the music that he enjoyed and in which he found inspiration. My appreciation to Dick Sisto for hipping me to this book.

Robert Inchausti on Merton:

Thomas Merton was the quintessential American outsider who defined himself in opposition to the world in both word and deed, and then discovered a way back into dialogue with it and compassion for it.

Special thanks to Chris Parker, Dick Sisto, Casey Zakin, and the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center.