Mal Waldron emerged on the mid-1950s jazz scene as a member of bassist Charles Mingus' group, the house pianist for the Prestige record label's frequent jam-session LPs, and a composer of brooding minor-key hardbop tunes and ballads. On this edition of Night Lights we'll hear music that Waldron wrote in the 1950s and early 60s, performed by John Coltrane, Jackie McLean, Dizzy Gillespie, Eric Dolphy, and Waldron himself.

"A Moody, Fluid Elegance"

Mal Waldron was born in New York City on August 16, 1925 to West Indian immigrant parents. He started as a classical pianist at age ten, took up saxophone at age 16 after hearing tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins, and then went back to piano in his early 20s after hearing alto saxophonist Charlie Parker. He felt that he could not keep up with Parker's advances on the instrument, but that he could keep pace with those of Parker's piano-playing peer in the bebop movement, Bud Powell. After gigging in the early 1950s with saxophonists Ike Quebec and Big Nick Nicholas, and finding himself more often than not in R and B environments that Waldron felt stifled his development, he came under the wing of bassist Charles Mingus and Mingus' Jazz Workshop ensemble.

Waldron later called his several years with Mingus "very fruitful… he showed me a lot about the piano and made me aware of possibilities in the piano, made me aware of sound as opposed to formal chord changes and harmonic structures." Mingus was just one of numerous influences that fostered the creation of Waldron's idiosyncratic sound-world. Jazz critic Francis Davis once described Waldron's music as

Crowded, low-ceilinged, and invariably fixated on a cluster of notes near middle C, Waldron's music as he plays it tends to be about tension and release—but sometimes just tension.

One of Waldron's early compositions was, in fact, called "Tension," originally written as a solo-piano piece during Waldron's Jazz Composers workshop days with Mingus. Several years later he filled it out for an ensemble that included trumpet, flute, and cello:

In the late 1950s and early 1960s Waldron appeared on many Prestige records, both as a leader and as a sideman, effectively serving as the label's house pianist and musical director, and writing a great deal of music for Prestige artists as well. (He once estimated that he had contributed 400 compositions during his association with the label.) In April of 1957 he led a date that included saxophonist John Coltrane, who was on the verge of making a major change in his lifestyle that would pave the way for his accelerated and innovative musical evolution over the next ten years, and who was also about to begin work with one of Waldron's influences, Thelonious Monk. Jazz writer Ashley Kahn wrote decades later that "Waldron had developed a style that layered a moody, fluid elegance and a liberal use of space and somber voicings over angular rhythms reminiscent of Monk—making him a perfect foil for Coltrane."

Jackie McLean, a frequent recording partner of Waldron in these years, also appears on our next selection, which comes from another significant musical relationship that Waldron formed in the late 1950s, with singer Billie Holiday. Waldron was recommended to Holiday by a network of jazz-community friends in 1957 as a replacement for her troubled accompanist, and remained with her until she died in 1959. The two meshed well together musically, and Waldron later said that "Billie helped me with my phrasing. She taught me to pay attention to the words of a ballad even when I was playing the instrumental version." Not long after her death, Waldron recorded a tribute album to Holiday that included a song that they'd written together called "Left Alone":

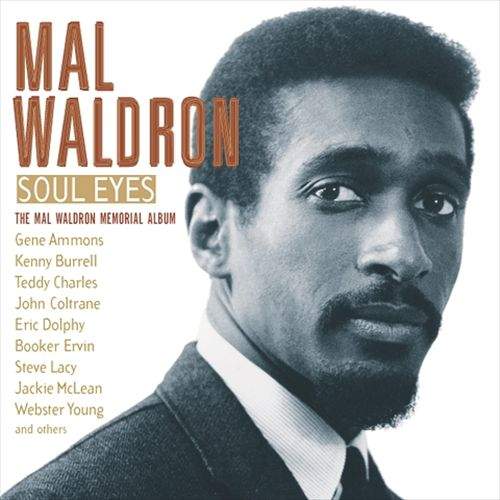

In a 1983 profile of Waldron for Coda magazine, Elaine Cohen wrote that Waldron's music has been described by jazz critics as "a rock, introspective, terse, hypnotic, disciplined, melodic, mesmerizing, economical, inventive, sizzling, subtle, and impossible to pigeonhole." His influences ranged from Duke Ellington, Bud Powell, and Thelonious Monk to Bela Bartok and Erik Satie. Unique and abstract in a way that lends itself especially well to improvising soloists, Waldron's music remains a relatively untapped source of material for jazz musicians today; the composition that has endured more than any other in the modern jazz repertoire is the ballad "Soul Eyes." The best-known recording was made by tenor saxophonist John Coltrane for his 1962 album Coltrane; Coltrane had also performed on Waldron's 1957 debut of the tune for Prestige.

Coltrane's recent musical partner, Eric Dolphy, had also crossed paths with Waldron for a brief but significant period in 1961. The two appeared together on bassist Ron Carter's Prestige album Where? and shortly thereafter for the album that some consider to be Waldron's neglected masterpiece, The Quest. Dolphy's angular, fiery off-center-bop approach proved a good fit for Waldron's music. Several weeks later Waldron and Dolphy would include some of the new music in their sets at New York City's Five Spot, and the ensuing albums from these sets have become landmark live recordings of early-1960s progressive jazz:

In 1963 Waldron undertook the first of what proved to be several projects scoring music for movies. The Cool World, a portrait of a troubled Harlem teenager based on a novel by Warren Miller, was directed by Shirley Clarke, who had recently turned Jack Gelber's jazz-saturated play The Connection into a movie, and who would also win an Academy Award in 1963 for a documentary on the poet Robert Frost. "Waldron's music," jazz critic Francis Davis wrote in the liner notes to a CD reissue of trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie's interpretations of the film score, "fierce even at its most lyrical and somber even at its most swinging-was one of the means by which Clarke imposed an adult's compassionate but emotionally distanced point of view on Warren Miller's adolescent-level narrative." Waldron told Davis that he got the scoring job as a result of his friendship with actor Carl Lee, who played a drug dealer in the film, and that he listened to Miles Davis' Lift To The Scaffold and Duke Jordan's Dangerous Liaisons, scores done by those artists for French films, for inspiration. "The tricky part for me, after accepting the assignment, was timing the music to the scenes." In 1964 Gillespie took his working band of the time, with Kenny Barron on piano and James Moody on saxophone, into the studio to record the movie's music for Philips:

In 1963 Mal Waldron suffered what he described at times as a "nervous breakdown," later elaborating that it had been brought about by a near-fatal overdose of heroin that left him unable to play piano for about a year. "When I came to I couldn't remember anything," he later told writer Alyn Shipton. "I didn't know who I was, my name, or anything. I couldn't remember any music—no chord changes, no tunes, nothing." Waldron taught himself to play again partly by listening to his own records. "Music, for me, was always like breathing," he said to Shipton. "If you don't breathe, you die, so having come back to life, for me it wasn't a choice." Waldron would continue breathing, both literally and metaphorically, for nearly another 40 years, making many more records and writing new music. I'll close with another Mal Waldron composition from his 1961 album The Quest that also offers a rare instance of Eric Dolphy playing clarinet; despite some of the reed problems that Dolphy experiences, it's a lovely performance, and indicative of the haunting beauty at the heart of Waldron's early music. Mal Waldron, Eric Dolphy, and "Warm Canto," on Night Lights:

More Mal

- Mal Waldron's Ecstatic Minimalism (Adam Shatz essay for The Nation)

- Mal Waldron (Wikipedia entry)