Roy Haynes has been called the father and keeper of modern jazz drumming, one of the most consistently inventive and enduring percussionists the music has ever known, and whose discography could function as an encyclopedia of 20th-century jazz that extends into the present day. On this edition of Night Lights we'll hear recordings that Haynes made between the ages of 25 and 45 with Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Stan Getz, John Coltrane, Chick Corea, and others, as well as some of his own small-group leader dates.

While Haynes' career on record reads like a roll call of jazz history, his discography also yields a number of notable dates under his own name. Whatever the date, his playing bears the unique stamp of what a DownBeat article described as

an eloquent, original thinker… the nontraditional hi hat phrases, the surprising bass drum accents, the across-the-bar cutting/spraying snare-drum commentary, the ride cymbal that alternately recalls the wind, a rainstorm, or scalding punctuation marks. The result is an omnidirectional approach to rhythm that sounds fresh on recordings dating from the 1940s through the present day.

Roy Haynes was born in Boston, Massachusetts on March 13, 1925, and played his first professional gig there in 1944. His high school career was cut short in part by his distracting tendency to entertain his classmates with thumb-drumming performances on his desk. After spending two years with former Louis Armstrong music director Luis Russell's band, he caught the ear of legendary saxophonist Lester Young and became a part of his group. It was the beginning of a long series of associations with landmark figures in jazz, which would include Charlie Parker and Miles Davis:

Haynes' style continued to evolve-writer Burt Korall describes the "broken rhythms, provocative syncopation, and improvisatory, Haynes-tailored techniques that no one has ever been able to duplicate." Though he operated most frequently in instrumental settings, he did sometimes back vocalists, and he did a long stint throughout the 1950s with singer Sarah Vaughan. He also appears on one of the hit vocal-jazz albums of the early 1960s, Etta Jones' Don't Go To Strangers:

Partly because he had such steady work with Vaughan throughout the mid-1950s, Haynes did not step out on his own as a leader till near the end of the decade. That long spell of backing a vocalist left some jazz fans worried that he might "have gone stale," as jazz critic Ira Gitler put it in the liner notes to Haynes' first studio efforts under his own name. That album, We Three, came in a trio setting, with the young, virtuosic Phineas Newborn Jr. on piano and Paul Chambers on bass, and offered proof that any concerns about Haynes having gone stale were unfounded:

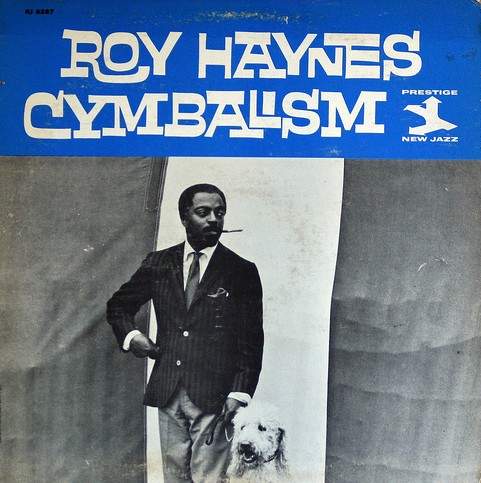

Haynes was nicknamed "Snap, Crackle" by bassist Al McKibbon to describe the drummer's evocative, multi-accented sound. Haynes also fashioned a reputation for sartorial excellence, winning an award along with Miles Davis from Esquire Magazine for his well-turned-out appearance. Haynes was also noted as a steady family man, and he wondered aloud to jazz writer Leroi Jones if this accounted for his relative lack of name recognition in the jazz world—in the early 1960s he was sometimes being voted for in jazz polls as a "New Star". Around this same time

He made an LP for the Impulse label, Out Of The Afternoon, that some consider to be his masterpiece as a leader, featuring a supporting cast of pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Henry Grimes, and the adventurous multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan Roland Kirk, making his sole appearance on an Impulse date:

During this same period Haynes was sometimes playing and recording with tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, during the era of Coltrane's so-called "Classic Quartet"-a time when one key member of that quartet, drummer Elvin Jones, was sometimes sidelined or unavailable. "Roy Haynes is one of the best drummers I ever worked with," Coltrane said in 1966:

I always tried to get him when Elvin Jones wasn't able to make it. There's a difference between them. Elvin's feeling was a driving force. Roy's was more of a spreading, a permeating.

Haynes returned the compliment, speaking frequently of the inspiration and intensity he derived from the saxophonist. Coltrane was just one of several leaders Haynes worked with throughout the 1960s; he was also an integral part of the young Chick Corea's late-1960s trio, and he also played again with Stan Getz, on the saxophonist's landmark 1961 orchestral album Focus:.

Roy Haynes' career would continue to add chapters into the 21st century, including a group appropriately called Fountain of Youth. Drumming seems to have always been a part of his life-force; as he told DownBeat in 2011,

This was a God-given thing to me. I had the feeling for it from day one, even before I had any drums. I didn't even have drumsticks. I'd be drumming on the wall, on the mirror, anything that felt good or sounded slick. My mother's dining room dishes.

Though the classic recordings we've been listening to are now a part of jazz history, the legacy of Roy Haynes is about doing your best to make history every time you sit down to play, now, in this particular moment. We close out with something from his 1971 Hip Ensemble album:

Many of the recordings heard on this program are available on the three-CD set A Life In Time: The Roy Haynes Story