In 1949 bandleader Artie Shaw, the so-called "King of the Clarinet" who had rocketed to fame at the end of the 1930s on the strength of hits like "Begin the Beguine," had been off the jazz scene for a couple of years, for any number of reasons—he was more interested in playing classical music, there was a recording ban on by the musicians' union, and the economic climate for big bands was turning frosty. But, as was the case several times throughout his career, Shaw started a new band- partly out of artistic restlessness, and partly out of financial need.

"Everybody liked it but the people"

Shaw tapped young, bop-influenced writers like Tadd Dameron and Gene Roland, and put together an outstanding saxophone section that included Al Cohn and Zoot Sims. They toured throughout the autumn and early winter, and at the end of the year Shaw took them into the studio for several marathon sessions that constitute the whole of their recorded legacy.

Shortly afterwards, Shaw dissolved the orchestra. "I had a really great band in 1949 — one of the finest bands I've ever led," he told Fresh Air's Terry Gross in 1985. "The musicians, man for man, the arrangements, everything. I had the best arrangers in the world writing for me. And everybody liked it but the people, as the gag goes."

Shaw goes longhair

Ironically enough, Shaw had considered abandoning jazz not long before putting the big band together. "There is more to music than ‘Stardust,'" he told Downbeat, and throughout much of 1949 he devoted himself to playing classical music—tagged by media wags in those days as "longhair"—with several city symphonies and doing some recordings for Columbia as well. In April he brought a large classical orchestra into New York's Bop City, drawing a huge but ultimately bored and indifferent audience.

Shaw's forays into classical music would have a profound effect upon his playing on the jazz records he made between 1949 and 1954. "My entire concept of what a clarinet could sound like changed," he later said. "It got pure, and a little more refined. Instead of a vibrato, I tried to get a ripple."

"George Shearing with a clarinet"

From 1950 to 1953 Shaw waxed a series of commercially successful but artistically indifferent records for the Decca label. In the autumn of 1953 he formed a new version of his 1940s small-group the Gramercy Five, partly to perform for money that would help pay off his tax bill, and partly because he wanted to have a go at serious jazz again. The new Gramercy Five, actually a sextet, had a modern, cool-jazz kind of sound; one critic called it "George Shearing with a clarinet." The group's performances in New York City got great reviews from the critics, and in 1954 Shaw took the band into the studio on several occasions. Over the next 50 years he'd often refer to these Gramercy Five recordings as the best he ever did.

Shaw broke up his Gramercy Five ensemble in 1954 and played a few desultory gigs with as part of an all-star jazz tour before putting down his clarinet and retiring from the music scene. He lived another 50 years, but he never recorded or performed in public again. (Shaw did organize a new big band in the 1980s and occasionally conducted it, but he did not play clarinet; that role was assigned to the orchestra's general front man, Dick Johnson.) His 1949-54 recordings stand as the final, brilliant chapter of a musical legacy that Shaw referred to as "a good-sized chunk of durable Americana."

More About Artie

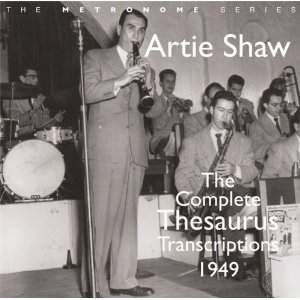

- Hep Records has recently released Complete Thesaurus Transcriptions 1949, which includes nearly all of the recordings that Shaw's 1949-50 big band made.

- Afterglow, the weekly program of jazz, ballads and American popular song that I also host, takes a look at Artie Shaw and the singers

- Listen to Fresh Air's 100 Years of Artie Shaw, which includes excerpts from Teri Gross' 1985 interview with the clarinetist

- Tom Nolan has published a new Shaw biography. I haven't read it yet, but for Shaw fanatics I can heartily recommend Vladimir Simosko's Artie Shaw: a Musical Biography and Discography

- George Kanzler reviews some recent reissues of late-period Shaw

- Earlier Artie: check out Jazzwax blogger Marc Myers' in-depth review of Mosaic Records' 1938-45 Shaw box-set