The spirit of jazz sometimes moves in ways that might not be as mysterious as they first seem. In the 1960s a number of jazz artists wrote and performed music for religious settings, sometimes with controversial results. Jazz was still seen as music at its most worldly, but for composers such as Duke Ellington and Mary Lou Williams, it was a natural way of expressing their spiritual beliefs-and, for them and for others, a new creative path to explore in jazz. Historian Michael McGerr and Indiana University African-American Choral Ensemble director Keith McCutchen join Night Lights this Easter week for a look at the origins, meaning, and music of the 1960s sacred-jazz movement.

Grief Leads To The First Jazz Liturgy

The intertwining of jazz and religion had begun to surface in the 1950s, in places as different as New Orleans jazzman George Lewis‘ album Jazz At Vespers and Gerry Mulligan‘s portrayal of a hip, saxophone-playing priest in the movie The Subterraneans. An Anglican priest, Geoffrey Beaumont, had composed a piece, "20th-Century Folk Mass," that was sometimes referred to as a jazz mass, though it contained almost no jazz elements. Ellington himself in 1958 had revisited his Black, Brown and Beige concert work with gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, whose vocals on "Come Sunday" and "The 23rd Psalm" gave the movement a strong devotional element.

But it was a grieving young jazz musician named Ed Summerlin who wrote one of the first significant extended sacred-jazz works, after learning in 1959 that his infant daughter was dying of a congenital heart defect. At the suggestion of his pastor, the 31-year-old clarinetist and jazz educator at North Texas State College composed a jazz setting for Methodist founder John Wesley‘s liturgy. After several performances, the jazz liturgy was recorded, and Downbeat gave it a 4 and a half star review. Two months later, in March of 1960, the work was featured on NBC‘s Saturday-night program World Wide 60.

Surprisingly, perhaps, most reaction from clergy was very positive; some viewers, however, denounced the music as "communistic," and one declared, "If you are going to have a jazz band in heaven, I‘ll go to hell!" Summerlin told Downbeat that jazz musicians were divided, too, about the aesthetic appropriateness of his work. On theological grounds, he said,

If the church is going to meet the needs of young people, it must recognize the fact that "The Old Rugged Cross" is not a very real part of our contemporary society.

Summerlin would go on to write many more sacred-jazz pieces and serve as the music director for the CBS religious show Look Up and Live, which often featured segments combining jazz music and spiritual messages.

Serving God Through Jazz

The 1960s were an opportune time for this kind of music; the Catholic Church was considering a modernizing reformation of the liturgy, and the Second Vatican Council would further enhance an air of openness to new ways of thinking and worshiping. One of the most prominent pioneers of sacred jazz was Mary Lou Williams, an artist whose career encompassed many different developments of jazz. Williams had dropped out of the jazz scene in the 1950s after converting to Catholicism; she spent her time running thrift shops and helping musicians who were struggling with drug addiction. Religious friends talked her into playing jazz again; one said to her,

God wants you to return to the piano; you can serve Him best there, for that is what you know best.

When Williams began to compose again, she directed much of her effort to writing music that served a religious purpose. "St. Martin de Porres" was a hymnal tribute to a 17th century Dominican lay worker who in 1962 became the first black person to be canonized by the Catholic Church, and who is the patron of interracial justice and of social workers-an obvious figure of inspiration to Williams, who would title her first sacred-jazz album Black Christ of the Andes, illustrating the way in which sacred jazz converged at times with the civil-rights movement of the 1960s. The album is both a spiritual offering and a tour de force of jazz history to that point.

1965: Convergence

Jazz and religion continued to converge as the 1960s progressed, perhaps most visibly in John Coltrane‘s landmark 1965 album A Love Supreme, which Coltrane called his "humble offering to God." That same year Argentine-born composer Lalo Schifrin and West Coast jazz artist Paul Horn collaborated on a jazz mass album that won two Grammy awards.

Jazz enjoyed another religious crossover of sorts in 1965 with the December Charlie Brown Christmas television program, which was scored by pianist Vince Guaraldi. It was actually Guaraldi‘s second spiritually-inspired jazz outing; officials in the northern California Episcopalian Church had also approached him about writing a modern jazz setting for the choral eucharist. Guaraldi obliged, and the live May 21, 1965 service at San Francisco‘s Grace Cathedral, with his trio accompanying a 68-member choir, was recorded. Some attendees were uneasy about it and complained to the Rev. Charles Gompertz that it sounded like supper music, to which he replied, "Of course. What does Communion represent but the Last Supper?"

"Every Man Prays In His Own Language"

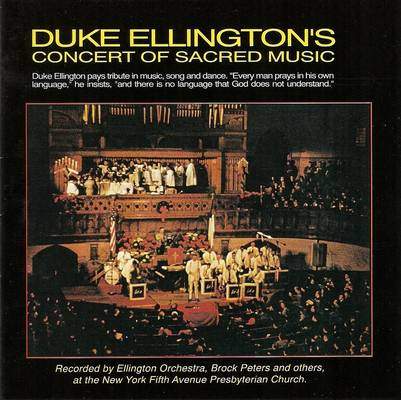

Just a few months after Guaraldi's performance, Duke Ellington premiered his first sacred concert at the same cathedral. Religious officials had been lobbying Ellington for years to do such a concert, and he finally overcame his ambivalence and agreed to it. Ellington later said that he prayed about his inner conflict; he was the most private of public figures and felt strongly that such a concert would have to be a complete act of worship, without any of the gamesmanship of show business.

The first sacred concert drew heavily on previously-composed materials, but it started with a new and vital piece, "In the Beginning God," with lyrics written by Ellington himself, as would be the case for all of his sacred concerts. Ellington‘s mantra for his sacred-concert music was, "Every man prays in his own language, and there is no language that God does not understand." Jazz was Ellington‘s foremost language, and in retrospect it‘s only natural that he would employ it in the service of his religious beliefs.

Ellington‘s first sacred concert got generally positive notices, and articles about sacred jazz began to appear in non-jazz, mainstream media magazines; some performances were broadcast on TV as well. In a lavish April 1966 feature devoted to the emerging jazz-goes-to-church movement, Ebony Magazine praised what it called Ellington‘s

historic moment. A type of music once disdained as being fit only for bars and bordellos was being performed in a sacred concert by a man who had helped earn for it the greatest respect.

Ellington would soon begin work on a second sacred concert, and his orchestra would play dozens of sacred concerts over the next several years.

The Role Of Priests, And Growing Controversy

Priests themselves played a part in the jazz-goes-to-church movement. Father Tom Vaughn, an Episcopalian priest, recorded an album with bassist Art Davis and John Coltrane‘s drummer Elvin Jones at the hip Village Gate club in New York City, and he also appeared on "The Tonight Show." The most prominent figure was Father Norman O‘Connor, often referred to as the "jazz priest". O‘Connor served on the Newport Jazz Festival board, hosted jazz radio and TV shows in Boston and New York throughout the 1950s and 60s, wrote a weekly jazz column for the Boston Globe, MC‘d concerts and sat on panel discussions. In his liner notes for Joe Masters‘ 1967 Jazz Mass album, O‘Connor took a shot at both 60s atheists and church establishmentarians, writing that

God isn‘t dead as you well know. The dead are those who want to keep us feeling guilty about guitars in church and pop songs at Mass and trumpets at Vespers. They are dead. They died in 1285.

That same year that the Vatican officially banned the use of jazz masses, calling them "distortions of the liturgy" and "music of a totally profane and worldly character." A backlash had begun to brew, and Downbeat ran an article headlined, "Jazz and Religion—End of a Love Affair?" In December of 1966 Duke Ellington prepared to perform a sacred concert in his hometown of Washington, D.C., only to find intense opposition to it from the city‘s Baptist Ministers Conference, which represented 150 area churches. Reverend John D. Bussey declared that Ellington lived in ways opposite from what the church stood for, denounced his performing in nightclubs, and called his music "worldly." Ellington responded that

I‘m just a messenger boy trying to help carry the message. If I was a dishwasher… in a night club, does that mean I couldn‘t join the church? No, man, I‘m just another employee….Doesn‘t God accept sinners anymore?

Attendance at the Constitution Hall concert wasn‘t quite 2/3 of capacity, with some tickets having to be given away, and proceeds intended to help the poor diminished.

While jazz masses and sacred jazz provoked dismay on the part of some church goers and church officials, they also inspired criticism from some jazz musicians who disliked organized religion in general, and satire from other quarters. One rather offbeat entry from the annals of 1960s sacred jazz is radio personality Al Jazzbo Collins' satirical sendup on jazz masses for his 1967 album A Lovely Bunch of Al Jazzbo Collins and the Bandidos.

Strengthening Bonds

As the 1960s wound down Mary Lou Williams was continuing to write and record sacred jazz, completing two jazz masses, and she had little patience for those who found such music offensive. "The ability to play good jazz is a gift from God," she told Ebony Magazine in 1966. "This music is based on the spirituals—it‘s our only original American art form—and should be played everywhere, including church. Those who say it shouldn‘t be played in church do not understand they are blocking the manifestations of God‘s will."

Like Williams, Duke Ellington continued to write and perform sacred jazz in the late 1960s. In 1968 he recorded his Second Sacred Concert after premiering it at New York City‘s St. John the Divine Church, before an audience of nearly 7000 people. At the concert Ellington teared up as he read the creed of four freedoms that his recently-deceased composing partner Billy Strayhorn had lived by:

Freedom from hate unconditionally; freedom from self-pity; freedom from fear of possibly doing something that might benefit someone else more than it would him; and freedom from the kind of pride that could make a man feel that he was better than his brother.

For Ellington, profound acts of musical worship were meant to strengthen the bonds that one felt with humanity as well as with God. His sacred concerts are an inspiring set of works written in the loss-stricken twilight of a great composer‘s life.

Sacred Jazz Postludes

- Music for Peace: the Sacred Jazz of Mary Lou Williams (Night Lights program)

- Jazz, Spiritually Speaking (Night Lights program)

- Jazz Goes to Church (1966 Ebony article)

- Read a 1959 article about the relationship between modern jazz and African-American church music (pg. 28 of Jazz Review

- View a sacred-jazz discography (Jazzministry.org)

- Douglas Payne on Hear O Israel, the 1968 album featuring Herbie Hancock (Sound Insights)

- Time Magazine in 1965 on the liturgical-jazz movement (Cool Creeds)

- Watch Duke Ellington and his orchestra performing the First Sacred Concert at San Francisco's Grace Cathedral in September 1965:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5j_oK2ocK0w

Also check out Harvey Cohen's recent book Duke Ellington's America, which devotes a considerably-detailed chapter to Ellington's sacred-jazz period.

Watch the Dave Brubeck Quartet perform "Forty Days," from Brubeck's Light In The Wilderness oratorio:

Special thanks to Phil Ford, Keith McCutchen, Michael McGerr, and George Schuller.