At the dawn of the 1960s pianist Freddie Redd made several albums for the Blue Note label filled with taut, punchy hardbop compositions, including the score for an avant-garde play about drug addicts called The Connection, in which Redd also acted. In the next hour we'll hear Redd performing his music with artists such as Jackie McLean, Tina Brooks, and Paul Chambers, as well as some of the recordings that preceded his Blue Note period.

"This Is Something That I Have To Do"

Freddie Redd was born in New York City on May 29, 1928. His father, who played piano, died when Freddie was only two, and though Redd's sister and his mother's subsequent longtime partner both played piano too, Redd himself didn't really take up the instrument until he was 18, serving in the military and stationed in Korea. While there in 1946 he ran into an acquaintance from Harlem, a supply sergeant who played a record for him that changed Redd's life. Years later he recalled:

It just blew my mind! It was Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie playing ‘Shaw Nuff.' Now I'd learned a little boogie-woogie to fool around with, but when I heard that, I thought: ‘This is something that I have to do.' It just spoke to me so strongly. From that moment on I started haunting the piano in the day room. I was there most of the time and met a few other enthusiasts of bebop… that's where I decided I would become a musician, a jazz musician at that.

Redd spent the next three years honing his jazz chops as he played at military bases and camps throughout Korea. He went back to the U.S. and left the military in 1949, about a year before war in Korea broke out; he said that many men in his outfit had re-enlisted and that it "got really wiped out" in the war.

In New York City, Redd soaked up the bebop scene on 52nd Street, listening intently to musicians such as Charlie Parker and Bud Powell. He played gigs in Syracuse and eventually landed a job with trumpeter Cootie Williams' band, touring with them for two years, and by the mid-1950s was working frequently as a leader and sideman on the New York City scene. "I was always learning; my ears were wide open," he said in 1988. Powell and Thelonious Monk were the biggest influences on his piano playing, which jazz writer Bob Blumenthal would describe decades later as "a barrelhouse take on Monk and Powell, and rollicking in the manner of Horace Silver, yet quite unique."

Making Connections

Redd spent the mid-1950s working with Art Blakey, performing in Sweden, appearing on studio dates with Art Farmer and Gene Ammons, and doing a tour of California with Charles Mingus. He ended up staying on the West Coast and in late 1957 recorded an album with an epic title track composed by him, "San Francisco Suite", a 13-and-a-half-minute-long musical depiction of the city that will be featured on a future Night Lights program.

After returning to New York City, Redd settled in Greenwich Village, but a bust for possession of marijuana stripped him of his cabaret card, required at the time for performers in the city. Still, Redd thrived in the Village's vibrant late-1950s scene, living in a large loft and mingling with writers, artists, photographers, dancers, and other people engaged in creative pursuits. One of them Gary Goodrow, was both a saxophonist and an actor, and it was Goodrow who hipped Redd to a new play by Jack Gelber going into production called The Connection. Goodrow was in the play and told Redd that it needed some jazz.

The Connection was a daring play for its time. Staged by the avant-garde troupe the Living Theater, it centered around a group of addicts sitting in a loft waiting to score heroin, with Redd's quartet, which included his friend Jackie McLean on saxophone, taking part in the action and playing music as well. Actors addressed or wandered into the audience, actors portraying the play's author and director appeared and argued with each other, and the subject matter attracted the attention of New York City law enforcement authorities. Establishment critics derided the play, but others gave it glowing notices, and writer Norman Mailer called it "dangerous, true, artful, and alive." Redd performed in the play for a year and a half, and during its run Blue Note producers Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff approached Redd about recording the music that he'd written.

Redd On Blue Note

Redd was excited, in particular because he'd had a chance to test his material nightly for a long time, and the studio results were a critical success. "Beauty, excitement, quality—you must get The Connection," DownBeat enthused in its review of Redd's score. "Freddie Redd has proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that jazz can be organized and orderly, and yet retain all the spontaneity and creativity of the informal jazz session." Redd made two different recordings of his music for The Connection-one on Blue Note with the same group that appeared in the play and subsequent movie, and one with a completely different lineup that included trumpeter Howard McGhee and saxophonist Tina Brooks, for the Felsted label:

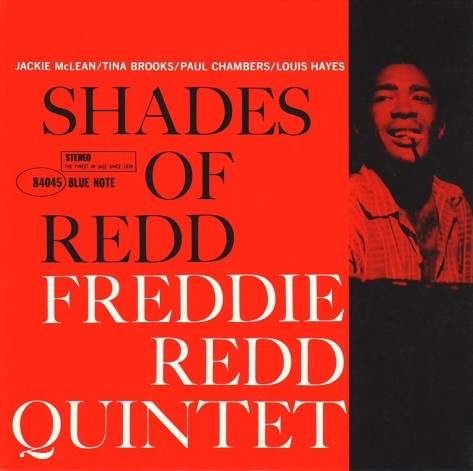

The critical success of the play The Connection and its accompanying Blue Note album led to further dates on the label for Redd. For his next album, Shades Of Redd, he brought back Jackie McLean and added tenor saxophonist Tina Brooks, who had served as McLean's understudy in The Connection, appeared on Howard McGhee's version of the play's music with Redd, and who made his own impressive run of albums for Blue Note during the same period that Redd was recording for the label. Redd wanted to blend the sound of tenor and alto saxophones without an accompanying trumpet, an unusual configuration for the time:

I loved the sound that they got. I gave them written charts, but we rehearsed every day at my house, bar-by-bar, phrase-by-phrase. I wanted to run all the nuances and make sure they understood exactly what I was trying to do.

Joe Termini, the owner of the Five Spot and Jazz Gallery clubs in New York City, had dubbed Redd "the Thespian" for his ongoing work in The Connection, and Redd appropriated the nickname for the opening track of his new Blue Note album:

Five months later Redd returned to Rudy van Gelder's New Jersey studio to make his third Blue Note album. Once again Jackie McLean, Tina Brooks, and Paul Chambers were on hand, and Redd brought expatriate trumpeter Benny Bailey on board as well. But Bailey had just come off a tour with Quincy Jones, and the band didn't have much time to rehearse. In 1988 Redd said,

I remember there was a lot of tension in the studio. We were taking a lot of time rehearsing. Right in the middle of it Alfred Lion got very angry. I can understand, looking back, but it seemed to end any rapport between us. We ended up arguing and Alfred said he was never going to release it. And he never did. It was my last recording for Blue Note.

The session would, however, eventually come out, first as part of a 1988 Mosaic box-set of Redd's Blue Note recordings, and then in 2002 as an individual CD. Heard today, it stands up as another high-level example of Freddie Redd's abilities as a composer, and of Blue Note's hardbop house sound, even on a day when the producer and the date's leader were at odds:

That session was the end of Freddie Redd's run on Blue Note, and for the next 50 years his career on record would be sporadic. After recording three LPs of his own music in the space of 12 months, between 1961 and 2007 Redd would make a total of only eight albums. He spent much of the 1960s and early 1970s in Denmark and France, returning to the United States in 1974. Mosaic Records' release of his collected Blue Note recordings in 1988 helped put his name briefly back into circulation, and in February 2007 he recreated the music of The Connection onstage at New York City's Merkin Hall with a band that included drummer Louis Hayes, who had worked with Redd on the Shades Of Redd lp.

Despite the economic challenges, scuffling, and general lack of recognition that marked Redd's life in music, he never expressed any regret for the path he'd chosen, ever since that day in 1946 when he heard Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie for the first time. In 1988 he reflected,

My motivation for getting into music in the first place wasn't to make a hell of a lot of money. I got into it and realized, ‘I got to eat, I got to pay rent, now what do I do? And how do I do that with grace, without having to kiss somebody's feet?' All I try to do is to maintain my own level and keep a high standard going with the music. Because that's all I've got. The business part I cope with because I've saved what I wanted to save. I've saved myself, I feel. I love music. Whatever comes is there because I feel that way about it. I never know what's going to come out; I just know that I WANT it to be there. And that feeling sustains me all the time.

Night Lights Extras And Outtakes

- The Connection: The Living Theater And Hardbop Jazz (Night Lights program)

Special thanks to Joe Milazzo.