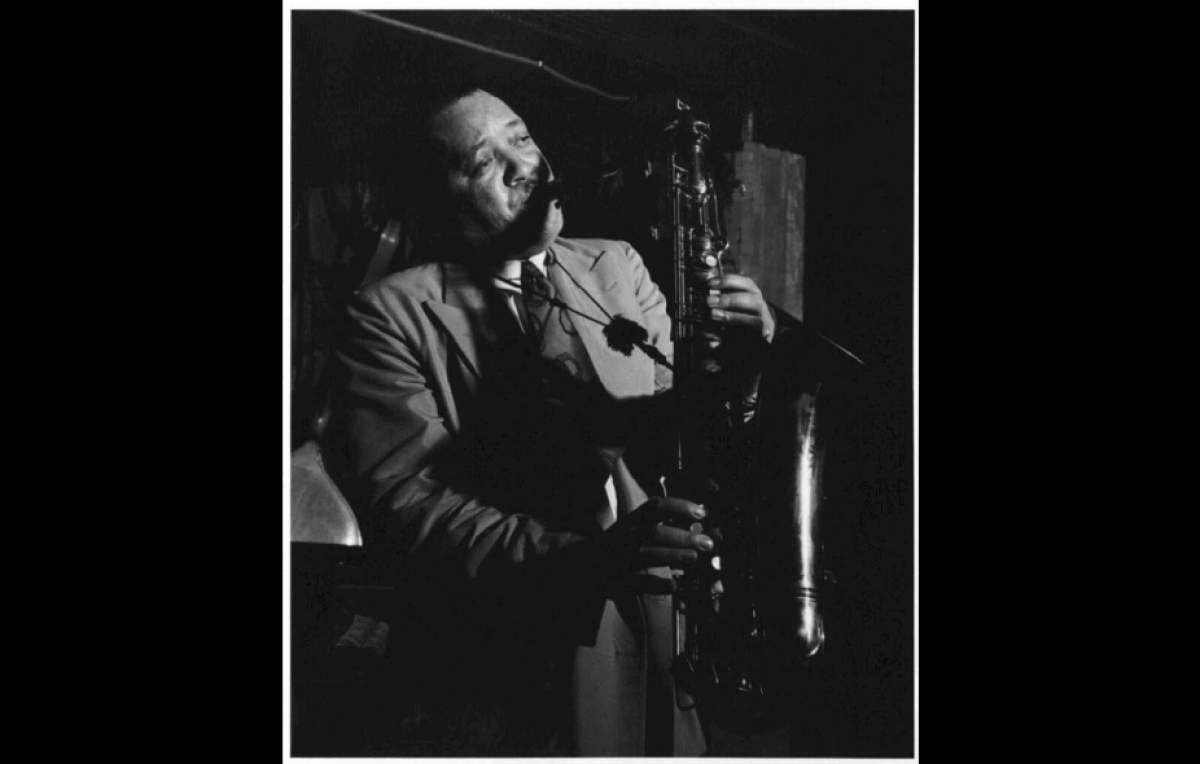

In 1945 Lester Young, one of the most influential saxophonists in jazz history, was released from the Army after a traumatic period of service spent mostly in a military prison. On this edition of Night Lights we'll hear recordings that Young made in the years immediately following the end of the war, as well as commentary from jazz scholar Loren Schoenberg, annotator of two Lester Young box sets for Mosaic Records, who delves into both the music and the myths of this phase of Young's career.

A Ballad Masterpiece

In late 1945, with World War II only recently concluded, saxophonist Lester Young was discharged from the Army, where he'd spent the last few months in the brutal confines of a Georgia military penitentiary after being court-martialed for drug possession. Young was in his mid-thirties, a musician who had risen to prominence with Count Basie's big band in the late 1930s and left many listeners and colleagues spellbound with his seemingly endless rhythmic and melodic invention, his dreamy cool lines and unique sense of swing. But Young had left Basie in 1940, and while he produced several landmark recordings in the early 1940s before returning to Basie in 1944, he seemed a bit adrift in this period. In late 1944 the draft board finally caught up with him, though he seemed the unlikeliest of candidates for military service.

Even before Young was released, jazz promoter Norman Granz had helped him land a recording contract for the Philo label, which would later become Aladdin. At his very first session he made a ballad masterpiece:

Granz also brought Young and pianist Nat King Cole together for a studio reunion. The two had made a memorable trio session with bassist Red Callender for Granz in 1942, and now, in 1946, he put them in a trio setting again, this time with drummer Buddy Rich:

One of the most enduring tunes associated with Lester in this period was titled in tribute to a high-profile jazz DJ who helped popularize the sound of bebop-Symphony Sid Torin:

By the time Young was done with the Army, bebop had taken a firm hold in the jazz world. While jazz writers such as Max Harrison have noted Young's incorporation of the new approach into his sound at times, Loren Schoenberg says he was still basically playing Lester. Here‘s a live performance of Young's "D.B. Blues" in 1949 at the Royal Roost, a bebop hotspot in New York City, with a group including Jesse Drakes on trumpet, Freddy Jefferson on piano, and Roy Haynes on drums:

While most accounts of Young's years following his traumatic experience in the Army paint a picture of decline, in the late 1940s he was still playing strongly and with creative verve much of the time. Loren Schoenberg says that his recording of "Sunday" gives evidence of that:

At his very next session for the Aladdin label, Young made what Schoenberg considers to be the defining recording of his late-1940s, postwar period:

The group that recorded "Easy Does It" included younger players such as pianist Argonne Thornton and drummer Roy Haynes. The small groups that Young led in these years often featured such musicians, and two years later Young made one of his strongest dates from this period with a group that once again included Haynes, as well as pianist Junior Mance:

During these years Young was also performing in Norman Granz's Jazz at the Philharmonic concert tours, alongside established and rising stars such as Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge, and Charlie Parker. Some of the concerts were recorded and released; here's Young in September of 1949, performing his "Lester Leaps In":

Granz would eventually sign Young to Mercury Records, and Young would record for him throughout the 1950s. At the beginning of the decade, he made a record that Loren Schoenberg sees as a prime candidate for top-tier postwar Lester Young: "It‘s a nice tune with an elliptical structure that Pres exploits as only he could. The piano playing is so in sync with the tenor - telepathy must be the right word for their communication."

Lester Young lived for another nine years, recording for Norman Granz's Verve label, touring with Jazz at the Philharmonic, and eventually succumbing to the health problems that had begun to dog him in his forties. He left behind more beautiful recordings-"haunting" is the adjective that Loren Schoenberg uses to describe them-always founded in his emotional honesty and his otherworldly sound, even as his ability to summon it declined. This performance of "Stardust" catches Young at a lovely moment on the cusp of his postwar years and at the beginning of the 1950s:

Special thanks to Loren Schoenberg.

Postwar Prez Extended

Much of the music on this program comes from Mosaic Records‘ new and amazing Lester Young box-set, with remarkably detailed and insightful annotations by program guest Loren Schoenberg. (And stay tuned for more prime Prez later this year in a forthcoming volume of the Savory collection.)

Here‘s recently discovered 1947 interview of Lester Young:

Max Harrison writes about this period of Young‘s career in Essential Jazz Records Volume 2:

"By the time we reach his Aladdin sessions many passages occur that he would not have played, perhaps could not have conceived, in the 1930s, there being for example a much greater degree of rhythmic abstraction. ‘After You've Gone,' with its extreme angularity of phrase and mocking use of clichés such as honks and repeated notes played with alternate fingerings, shows how, when a straightforward swinging performance was expected, he could impose something quite different.

"Young's powers as a ballad player were shown to be extraordinary in the period under consideration here, his interpretations being uncommonly slow, often of surprising poignancy and at the same time of enhanced rhythmic flexibility… as Andre Hodeir has said, he produces music that is ‘like a negative image of the original, a cleaned-up, retouched and disturbing image.' Further instances of Young's melodic creativity and capacity for sustained linear thought are ‘I'm Confessin'‘, ‘She's Funny That Way‘, making a particular use of the tenor saxophone's lower register, and ‘On The Sunny Side of the Street‘, which recaptures the mood of his performance in the 1944 film Jammin' The Blues:

"A comparable type of sustained intensity is found in Young's blues playing, of which ‘Jumpin' With Symphony Sid' and ‘No Eyes Blues' can serve as contrasting examples. Here, as in the ballads, he is shown to have a kind of strength not always evident in his big-band appearances. And nobody worked this idiom with greater originality than he, especially noteworthy being his avoidance of traditional flattened blue notes without any loss of blues feeling.

"Though he still followed Frankie Trumbauer in avoiding vibrato, his tone is larger than in the 1930s, more virile, even combative. The assertion of his beautifully-sculpted stop-time passages on The New Lester Leaps In, the vividness of his best ideas, their sheer communicative force, as on ‘Movin‘ With Lester‘ or ‘Just Coolin‘‘, should be obvious. Young's affinities with bop can be heard most clearly, though, in the music of the sextet which did the June 1949 session and more especially in the many live recordings taken of that band. For instance, their March 1949 Royal Roost version of D.B. Blues is very boppish and is one of a considerable number of performances which demonstrate that Young was at home amid the new music's turbulence. Such occasions were recreated by the churning excitement of the above ‘Jammin' With Lester‘, with its high-stepping McGhee solo; and he was indeed well-suited by the forceful ensemble backing he received on this second Aladdin session."

Lester Young and Charlie Parker performing as part of a Jazz at the Philharmonic concert: