Trombonist, composer and arranger J.J. Johnson was one of 20th century jazz’s brightest lights, and his discography provides a diverse overview of the music across some of its most vital decades.

Trombonist J.J. Johnson was a bebop pioneer on his instrument, a leader of many outstanding small-group hardbop dates, and a notable composer as well whose works sometimes ventured into the Third Stream meeting ground of classical and jazz as well as TV and film scores. On this edition of Night Lights we’ll hear him in all of those musical contexts, in the company of fellow jazz greats such as Bud Powell, Clifford Brown, Freddie Hubbard, and others.

Trombonist, composer and arranger J.J. Johnson was one of 20th century jazz’s brightest lights, and his discography provides a diverse overview of the music across some of its most vital decades. Johnson was born in Indianapolis, Indiana on January 22, 1924, and as a child first took up piano before switching to trombone as a teenager. He was still a teenager when he hit the road with Snookum Russell’s band in 1942, with his initial approach on trombone rooted in swing and influenced by musicians such as trumpeter Roy Eldridge and saxophonist Lester Young. Johnson came of musical age with the mid-1940s big bands of Benny Carter and Count Basie, where he also undertook his first arranging and composing efforts, and he appeared at one of promoter Norman Granz’s first Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts.

By 1945 Johnson was under the spell of the emerging bebop movement led by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, and he became the first trombonist to adapt the faster, more complex music to his instrument. Ben Ratliff, writing about Johnson in the New York Times after his death in 2001, said that “In transferring bebop to the trombone, he used a clean, dry tone and short notes. He was often wrongly assumed to be playing the valve trombone, which allows easier articulation than the slide trombone.” Ratliff was alluding to Johnson’s remarkable velocity on an instrument previously considered to be rather unwieldy and better suited for Dixieland and big band settings. Fellow trombonist and Indianapolis native David Baker cited Johnson’s far-reaching influence in 1997, saying that “Technical feats that were inconceivable prior to Johnson are now commonplace, and the attitude that the trombone is capable of anything that saxophones and trumpets can do is now generally taken for granted.”

Here’s an early example of Johnson’s prowess as a bebop trombonist, with bop piano master Bud Powell helping to propel the musical proceedings. J.J. Johnson and “Jay Jay,” on Night Lights:

Trombonist J.J. Johnson in 1946 performing his composition “Jay Jay,” with Cecil Payne on alto sax, Bud Powell on piano, Leonard Gaskin on bass, and Max Roach on drums.

In addition to his numerous bebop dates throughout the late 1940s, Johnson also participated in trumpeter Miles Davis’ landmark Birth of the Cool sessions that expanded jazz’s musical palette beyond its big band and bebop colorings. But in 1952 Johnson took an indefinite hiatus from the jazz world, in part to win a struggle with drugs that he had been waging for several years, like so many other musicians of his generation. For two years he worked as a blueprint inspector for the Sperry Gyroscope Company. He didn’t abandon jazz completely, making one of his finest albums for the Blue Note label in 1953 with rising young trumpet star Clifford Brown. Johnson’s composition “Turnpike” is a standout moment, cited by his biographers Joshua Berrett and Louis G. Bourgois III as “a multifaceted piece with allusions to Paul Hindemith, Count Basie, and others.” J.J. Johnson and “Turnpike,” on Night Lights:

J.J. Johnson in 1953 doing his composition “Turnpike,” with Clifford Brown on trumpet, Jimmy Heath on tenor sax, John Lewis on piano, Percy Heath on bass, and Kenny Clarke on drums. By 1954 Johnson was fully back on the jazz scene, and that same year he teamed up with Danish native and fellow trombonist Kai Winding to form a popular quintet that lasted for two years, even scoring a minor hit with their recording of Cole Porter’s “It’s All Right With Me.” Johnson’s haunting ballad “Lament,” which would become a jazz standard, was among the first pieces they recorded; J.J. Johnson and Kai Winding, on Night Lights:

Trombonists J.J. Johnson and Kai Winding performing Johnson’s composition “Lament,” from their 1954 album Jay And Kai, with Billy Bauer on guitar, Charles Mingus on bass, and Kenny Clarke on drums.

Popular though it was, by 1956 the Johnson-Winding combo had run its course for both artists, though they would reunite for three more albums in the 1960s. Johnson began his own small group that recorded frequently for the Columbia label into the beginning of the 1960s, with the results now considered some of the trombonist’s finest work as a small-group leader. Jazz scholar Loren Schoenberg describes it as “involved in a vital dialogue with jazz’s past, present, and future…here was a composer/arranger/improviser who exemplified Arnold Schoenberg’s dictum that the best written music should sound improvised, and the best improvised music should sound written.” He cites Johnson’s 1960 recording of his composition “Aquarius” as “… really something new for J.J., with rolling triplets played by saxophonist Clifford Jordan and pianist Cedar Walton over the dirge-like trombone/trumpet unison lines… during the final chorus, the various instrumental choirs alternate in prominence with a degree of ensemble perfection—blend, intonation, phrasing, and dynamics—that is a Johnson trademark.” J.J. Johnson and “Aquarius,” on Night Lights:

Trombonist J.J. Johnson performing his composition “Aquarius,” with Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Clifford Jordan on tenor sax, Cedar Walton on piano, Arthur Harper on bass, and Albert Tootie Heath on drums, from Johnson’s 1960 album J.J. Inc.

Though Johnson is frequently hailed in jazz histories for his innovative prowess as a trombonist, he also made a name for himself as a composer of extended pieces that fit into the emerging so-called Third Stream movement that championed a mixing of jazz and classical music. Like many other jazz musicians of his generation, Johnson was a classical fan, counting Paul Hindemith and Stravinsky among his influences. His ten-minute “Poem For Brass”, recorded by Third Stream godfather Gunther Schuller in 1956, paved the way for more such work, including commissions from the Monterey Jazz Festival and from Dizzy Gillespie, who asked Johnson to compose an entire suite in the manner of “Poem For Brass.” The resulting 1961 album Perceptions became a high mark in Johnson’s compositional history, and we’ll hear Gillespie performing its opening movement; we’ll also hear Johnson doing his own version of one of his Monterey commissions, “El Camino Real” in a 1964 big-band setting. First, here’s Dizzy Gillespie performing J.J. Johnson’s “The Sword of Orion,” on Night Lights:

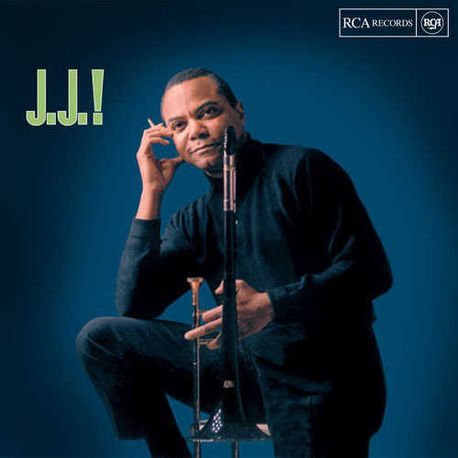

J.J. Johnson performing his composition “El Camino Real,” from his 1965 big-band album J.J.! Dizzy Gillespie before that performing “The Sword of Orion” from Johnson’s extended work Perceptions, recorded in 1961.

Johnson’s musical career took a notable turn in the late 1960s after he signed with a firm that produced TV commercials, eventually moving to Los Angeles in 1970 to work in the film and TV score business. His love of jazz persisted, pronounced emphatically in a DownBeat interview he gave that same year in which he spoke of his plans to continue as a jazz performere. Among the films and TV shows that Johnson helped to score were Shaft, Cleopatra Jones, Starsky and Hutch, The Mod Squad, The Six Million Dollar Man, and the 1972 Harlem-set blaxploitation film Across 110th Street. From that movie, here’s singer Bobby Womack and Johnson’s title song, on Night Lights:

Bobby Womack performing his and J.J. Johnson’s title song from the 1972 film Across 110th Street. Johnson continued to work in the film and TV industry for the next few years, though he did venture out on the road in the late 1970s and made jazz albums in the early 1980s. In the late 1980s he moved back to his hometown of Indianapolis and put together a new combo that recorded two live albums at New York City’s hallowed Village Vanguard. From one of those albums, here’s J.J. Johnson and “Why Indianapolis, Why Not Indianapolis” on Night Lights:

Trombonist J.J. Johnson performing his composition “Why Indianapolis, Why Not Indianapolis” with Ralph Moore on tenor sax, Stanley Cowell on piano, Rufus Reid on bass, and Victor Lewis on drums, from Johnson’s album Quintergy, recorded live at New York City’s Village Vanguard in 1988.

Johnson remained immersed in jazz activities for the rest of his life after his return to Indianapolis. He remarried in 1992 after his longtime wife Vivian passed away in 1991, dedicating an album in her name the following year. After becoming ill with prostate cancer, he retired from performing in 1997 and eventually chose to take his life in February 2001 at the age of 77. His late-period burst of work that preceded his illness such as the small-group outing Heroes and his collaboration with composer and arranger Robert Farnon on Tangence gave his illustrious career a broad and suitable finale, and I’ll close with music from one of his last projects. The 1996 album The Brass Orchestra found Johnson revisiting some of his earlier work in a Third Stream vein, including music from Perceptions, as well as new pieces and arrangements such as this one, orchestrated by fellow Hoosier and trombonist Slide Hampton--J.J. Johnson and “Enigma” on Night Lights: