In 1959, saxophonist and composer Jimmy Heath returned to the jazz scene. He‘d been away for awhile-five years-and he was a bit anxious about catching up. In hindsight he needn‘t have been; Heath and his brothers, drummer Albert Tootie Heath and bassist Percy Heath, a cornerstone member of the Modern Jazz Quartet, would become one of the most significant jazz families to emerge in the 20th century, and many of Heath‘s compositions have become jazz standards. But in 1959 he was a thirty-two year old recovering addict who had yet to make a recording date under his own name.

"Little Bird" And First Flights

Jimmy Heath was born in Philadelphia on October 25, 1926. An early fan of alto saxophonists Benny Carter and Johnny Hodges, his life as a saxophonist began in 1941 when his father gave him an alto saxophone for Christmas. The first thing the inquisitive-minded Heath did was to take the saxophone completely apart, then reassemble it. He played for a while with Nat Towles‘ territory band in the mid-1940s, then formed an experimental big band that included young, up-and-coming Philadelphians such as Benny Golson and John Coltrane. In those Charlie-Parker-crazed days of the late 1940s, Heath acquired the nickname "Little Bird"-one of the reasons why he ultimately took up tenor saxophone instead, in a bid to develop his own sound and identity. He eventually landed a job with Dizzy Gillespie‘s band, played and recorded with trumpeter Kenny Dorham, and in 1953 made a now-legendary Blue Note Records date with Miles Davis and J.J. Johnson that included one of Heath‘s first notable compositions, "C.T.A."

But the shadow of heroin addiction, the plague of mid-20th-century jazz, had fallen across Heath‘s life, and he later called the mid-to-late 1950s "a void, a real waste, the worst and darkest period of my life." Arrested in 1953 on a narcotics charge, he spent six months in the federal government‘s Lexington, Kentucky drug-rehabilitation penitentiary. Released in mid-1954, by January 1955 he was back, this time serving a sentence of 53 months in a Pennsylvania prison. While in prison he organized a band and managed to smuggle some of his compositions out through his brother Tootie, who gave them to trumpeter Chet Baker to record for his 1956 album Playboys.

"Passionate But Never Of A Purplish Hue"

When he got out in 1959, Heath was determined to stay clean, and to re-establish and develop the career in music that had been halted so abruptly in the early 1950s. He initially had to contend with parole-based travel restrictions that ultimately forced him to give up a high-profile opportunity with Miles Davis‘ band. But Kenny Dorham had hipped Riverside Records producer Orrin Keepnews to Heath‘s imminent release, and in September 1959 Keepnews brought the saxophonist into the studio to make his debut as a leader. The resulting album, The Thumper, confirmed Dorham‘s sage advice and laid the foundation for Keepnews‘ remark, decades later, that Heath "was one of the most skillful and creative composers, arrangers, players, and bandleaders around." Here‘s the leadoff track, written while Heath was serving his time:

DownBeat Magazine reviewer Don DeMichael praised The Thumper as "an LP of substance," citing both Heath‘s writing and what he called Heath‘s "manly" saxophone work, "passionate but never of a purplish hue."

For his next album, Heath and Riverside producer Orrin Keepnews decided to up the musical ante and present Heath‘s music in an expanded, tentette musical setting. Brothers Cannonball and Nat Adderley and trumpeter Clark Terry were so enthusiastic about Heath‘s writing for the date that they all but insisted to Keepnews that they be included on the date. Keepnews copped a trademark line from TV show host Ed Sullivan for the album‘s title, Really Big! It included a ballad tribute to Heath‘s newly-wedded wife Mona, and this composition, named in honor of Heath‘s older brother who played on the date as well, Percy Heath:

Brothers And Colleagues

With two well-received albums as a leader now under his belt, Heath was given a prominent profile in the March 2, 1961 issue of DownBeat. Titled "The Return of Jimmy Heath," the article was candid about the reason for Heath‘s absence from the jazz scene for much of the 1950s, and provided the fullest biographical portrait of the saxophonist to date. Pete Welding wrote that

The events of the last two years--his release from prison, marriage and the birth of his first child, recording work, and a steadily increasing demand for his services, both as a horn man and writer--all have combined to exert a stabilizing influence and to strengthen his resolution to keep straight.

Shortly after the article appeared, Heath returned to the studio to make his next Riverside recording, once again enlisting the talents of both brother Percy and brother Tootie. Befitting the family affair of the date, one tune was based on a melody that Heath‘s mother used to sing to her children:

Heath's Riverside recordings featured him in the company of musicians such as Freddie Hubbard, Wynton Kelly, and other top players of the times. In addition to the six albums that he made as a leader for the label between 1959 and 1964, he also appeared on a number of LPs as a sideman, sometimes contributing arrangements and compositions for musicians such as trumpeters Nat Adderley and Blue Mitchell, pianist Elmo Hope, and vibraphonist Milt Jackson, whose Riverside recordings will be the subject of a future Night Lights program. With his seemingly infinite ability to craft interesting variations in a blues-based hardbop idiom, Heath played a key role in the Riverside sound of the early 1960s, imprinting any date that he was on with his musical identity. Here he is in 1960 with bassist Sam Jones in a performance of Heath‘s composition "All Members":

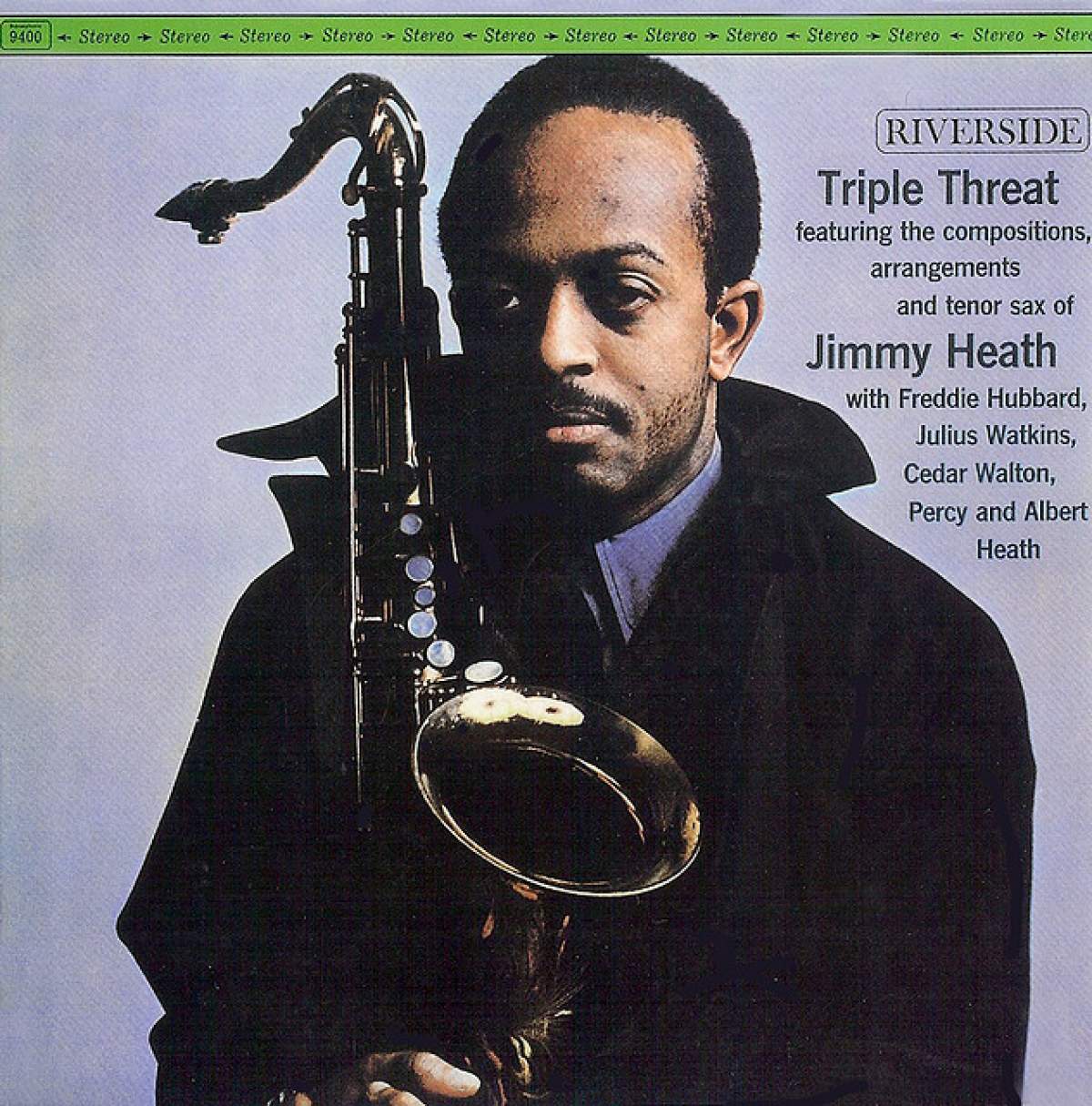

Heath's 1962 album Triple Threat, the title an homage to his strengths as a composer, arranger, and player, added a French horn to a standard quintet lineup, and on the 1963 album Swamp Seed he doubled up the French horns and put a tuba into the mix:

After his 1964 On The Trail album for Riverside, which folded that same year, Jimmy Heath went without a label for some time, but his career continued to develop. In the 1970s he teamed up with Percy and Tootie Heath to form the Heath Brothers, and he eventually became involved in jazz education as well. He continued to write and record into his 80s, and in 2010 he published his autobiography, I Walked With Giants. His compositions gained a hold in the jazz canon as enduring examples of small-group, mid-sized, and big-band hardbop at its finest. Jimmy Heath became one of the longest success stories of modern jazz---and that story‘s most important early chapter came on Riverside Records, when a highly-gifted artist in his mid-30s turned his musical and personal life around and built the foundation of his legacy in jazz. We close the program with music from his final Riverside album, a tune that Miles Davis would record shortly thereafter-"Gingerbread Boy":

Heath Bonus Tracks

Read Jimmy Heath: Endless Search

Listen to Jimmy Heath's "Nice People":