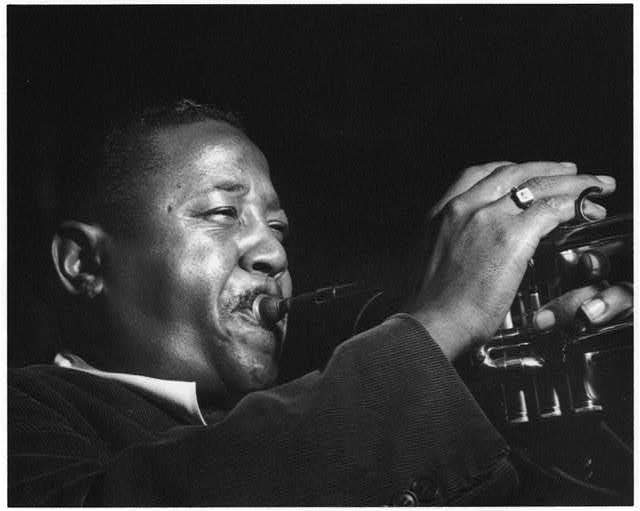

They called him "Little Jazz," but he was born David Roy Eldridge on January 30, 1911 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Roy Eldridge has often been called the link or bridge between Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie. He was indeed a strong influence on Gillespie, who called him "the Messiah of our generation," and he certainly admired Armstrong, who he said taught him how to build a story out of his solos. Biographer John Chilton writes that

The combination of Armstrong's ingenious thematic developments and the fast-flowing lines that Roy had based on the saxophone-playing of Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter, plus the hard-won instrumental virtuosity and a natural sense of harmonic daring, all jelled and formed the basis of the Eldridge trumpet style. Based on these foundations Roy created improvisations that were increasingly full of what were then considered (in jazz) to be advanced harmonies, often using chromatic substitute chords, thus pioneering an approach that others developed into ‘modern' jazz.

But Eldridge was much more than some sort of simplified "link" between two other hugely talented and complex musicians, and he was a musical role model for many who followed, such as trumpeter Joe Wilder. "We should all bow our heads to Roy because he's the one who made us take risks playing the trumpet," Wilder said. "He did things that nobody would ever dare to do."

"Portrait of Little Jazz" features the music Roy Eldridge recorded from the late 1930s to the end of the 1950s—music that gives a sense of the breadth of his accomplishment, and of his joyous artistic fire. The trumpeter had a competitive temperament that was legendary. Trombonist Trummy Young once described him as a "bubbling gladiator," and saxophonist Scott Hamilton, who played with Eldridge in the 1970s, said he viewed other trumpeters as though it was "the Old West, six shooters and all…'Every time I try to relax another one of them comes through the door."

Spark Plug of the Band

Eldridge made his way up in the 1930s jazz world playing with the bands of Elmer Snowden, Teddy Hill, and Fletcher Henderson. He frequently teamed with tenor saxophonist Chu Berry as well. In the 1940s he did high-profile stints with two of the most popular big bands of the era—those of drummer Gene Krupa and clarinetist Artie Shaw. In Krupa's orchestra he and singer Anita O'Day scored a hit with a daring inter-racial duet, "Let Me Off Uptown" that would become a periodic reunion staple for both perfomers…and Shaw called him "the spark plug" of Shaw's 1944-45 band.

With both bands, however, Eldridge experienced the pain of being a black musician in a white orchestra touring the segregated America of the 1940s, and he actually took to carrying a gun for his own protection. "Droves of people would ask for his autograph at the end of the night," Shaw said, "but later, on the bus, he wouldn't be able to get off and buy a hamburger with the guys in the band." Despite these persistent and enraging injustices, Eldridge made some of his most classic sides with Krupa and Shaw, with "Rockin' Chair" and "Little Jazz" representing this period in the program.

Riding High As a Leader

Roy Eldridge also led his own big band and a smaller group in the 1940s, and he recorded as a leader for Decca throughout the middle years of the decade, maintaining a star profile, even as the new music of bebop began to gather force and one of its foremost practitioners, the young trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, continued to develop his own style in a way that went beyond his early imitation of Eldridge-an emergence that would soon have some younger jazz critics and musicians proclaiming Gillespie as the new king of the trumpet.

In 1943 however, Eldridge was riding high with the public, and Downbeat readers voted his group as their favorite small combo. We'll hear two of his Decca sides from that year, including "Stardust" and "The Gasser," which Eldridge biographer John Chilton singles out as "one of Roy's greatest achievements, a performance packed with ingenious ideas and a grand passion."

"The Spirit of Jazz"

In the mid-1940s Eldridge began what would prove to be a significant association with the impresario Norman Granz, creator of the Jazz at the Philharmonic concert tours, which featured many stars of the swing era in extended, crowd-pleasing on-stage jams. Eldridge, who thrived in competitive settings, took naturally to the all-star concerts, which also supplied him with a decent income. He recorded for Granz in the studio as well throughout the 1950s, leaving behind an outstanding body of work that Mosaic Records would release in box-set form five decades later.

Granz was a lifelong advocate for Eldridge, saying, "I know of no other musician whose playing better depicts and typifies the spirit of jazz." And Eldridge, whose experiences at the hands of racism had left him sometimes guarded and edgy in his remarks about some figures in the jazz world, returned Granz's praise: "Norman made sure the cats got a decent living, he was the first to break down all the prejudice, and put the music where it belongs. They should make a statue to that cat." Working primarily with small groups and occasionally with strings, Eldridge flourished on Granz's Verve label.

Eldridge began recording for Verve not long after his return from Europe, where he'd spent some time at the beginning of the 1950s—an expatriate experience that's been attributed both to Eldridge's desire to take a break from the American jazz scene, where the rise of bebop had left him feeling musically alienated, and to his need to get away from the country's ongoing atmosphere of segregation and racism. One of Eldridge's most dynamic and inspirational colleagues had also once taken a very extended European holiday—tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. Eldridge had worked and recorded with Hawkins before, but in the years following his return from Europe, he frequently teamed up with the saxophonist for live performances and occasional studio recordings.

The two loved to talk about clothes, cars, cooking, and sports… a casual conviviality offset by the intense expertise they brought to the music they made together. Eldridge deeply admired Hawkins' playing and years later said, "He was the only one that I didn't know what he was going to play next in his solos." It was Hawkins, along with saxophonist Benny Carter, who had influenced a young Eldridge to play trumpet in a more harmonically complex, saxophone-like way. "Portrait of Little Jazz" includes recordings the trumpeter made with both of them.

From the 1960s On

Roy Eldridge remained active throughout the middle-late decades of the 20th century, playing festivals, recording for Norman Granz's Pablo label, and performing regularly and holding court throughout the 1970s at Jimmy Ryan's Club in New York City. Only a heart attack in 1980 would slow him down, forcing him to give up the trumpet after the doctor warned him that playing in his usual vigorous manner would be hazardous—Eldridge knew he wouldn't be able to restrain himself if he tried playing gently all the time. But he continued performing by singing and occasionally playing drums and piano throughout the 1980s. When his wife Vi died, however, in February of 1989, a few days after their 53rd wedding anniversary, he lost the will to live and passed away just three weeks later. Jazz writer Dan Morgenstern reported that the church was filled with mourners and that Dizzy Gillespie said he almost didn't come because, "I didn't want so many people to see me cry."

Origin of the Nickname

"Little Jazz" was bestowed upon Eldridge in the early 1930s, when a bandmate (Otto Hardwick, of Duke Ellington fame) told the 118-pound trumpeter, then barely out of his teens, "I'm going to call you Little Jazz, because you've always got that horn in your face."

More Roy Eldridge

- Roy Eldridge: Little Jazz Giant (excellent biography by John Chilton)

- Portraits of Harlem (Night Lights show featuring Eldridge's "I Remember Harlem")

- Art Tatum: the Group Masterpieces (Night Lights show that includes Eldridge and Tatum's performance of "Moon Song")

Watch Roy Eldridge and Anita O'Day perform "Let Me Off Uptown" with Gene Krupa's orchestra in 1942: