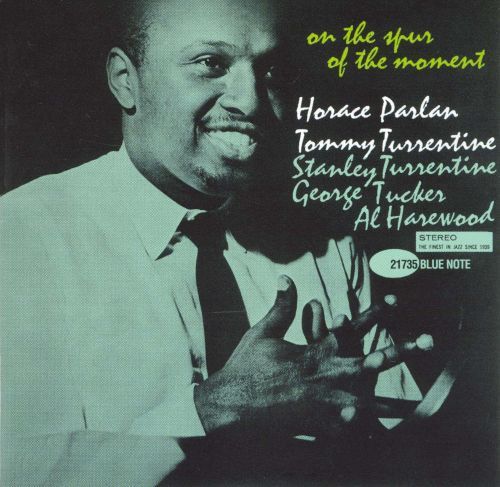

One of five studio albums that pianist Horace Parlan and saxophonist Stanley Turrentine appeared on in 1960-1961.

Pittsburgh has produced many great jazz artists, and at the beginning of the 1960s two of them teamed up to make a notable series of albums for the Blue Note label. Tenor saxophonist Stanley Turrentine and pianist Horace Parlan‘s soulful hardbop sound was often filled out by Stanley‘s brother Tommy on trumpet and underpinned by the in-the-pocket combination of bassist George Tucker and drummer Al Harewood. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear some of their studio recordings, as well as a live date featuring guitarist Grant Green.

The American city of Pittsburgh is best known for its production of steel—but in the 20th century, it also gave birth to some of jazz‘s most outstanding musicians—especially pianists, including Mary Lou Williams, Earl Hines, Erroll Garner, Dodo Marmarosa, Sonny Clark, Ahmad Jamal, and Billy Strayhorn. Any such roll call must also add pianist Horace Parlan, born in Pittsburgh on January 19, 1931. Parlan, the son of a preacher, took up piano at the age of 8. He had been struck by polio just three years earlier, leaving him unable to use the fourth and fifth fingers of his right hand. Much like guitarist Django Reinhardt, whose fingers had been badly damaged by a fire, Parlan was able to overcome his physical challenge to forge what jazz writer Bob Blumenthal has described as "an instantly recognizable voice out of an intensely rhythmic attack, a darkly rich harmonic imagination and a preference for brittle, open melodic phrases." In the early 1950s he began to play professionally, honing his craft under the tutelage of trumpeter, bandleader and fellow Pittsburgh native Tommy Turrentine, whose group also included brother Stanley on saxophone.

Tommy Turrentine was the older brother, born in 1928, while Stanley was born in 1934. Their father was a saxophonist, and all five of his children received musical training; Stanley later recalled that they would listen to big bands on the radio while his father tested them to identify who was playing certain instruments. In addition, "There was always music in the neighborhood," Turrentine told writer Gene Lees—people either playing instruments or records seemingly wherever he went. In addition, Pittsburgh area saxophonist Carl Arter took the fourteen-year-old Stanley under his wing at the urging of Tommy Turrentine, beginning what became a longstanding tutorial relationship that would lead the younger Turrentine in later years to refer fondly to Arter as "my mentor."

Stanley Turrentine paid his first professional dues playing with blues guitarist Lowell Fulson‘s band on a tour of the South during the height of the Jim Crow era—a band that included Ray Charles on piano and vocals-- and went on to become a part of saxophonist Earl Bostic‘s popular group for several years before having to serve two years in the army, where he continued to play in a military band. He developed a unique sound that seemingly touched on everything from swing and bebop to R & B that would ultimately fit right into the emerging hardbop style of the late 1950s.

Horace Parlan left Pittsburgh for New York in 1957 to play with bassist Charles Mingus and by 1960 was working with saxophonist and Blue Note artist Lou Donaldson, while Stanley and Tommy Turrentine did a two-year stint with drummer Max Roach at the end of the 1950s. The Parlan-Turrentine team‘s recorded legacy comes from a brief but productive 15-month stretch across the waning days of the Eisenhower presidency into the beginning of the Kennedy administration. Their first studio encounter occurred in January of 1960, and it‘s a bit of an outlier, as it wasn‘t made for Blue Note, and it was done as a leader date for Tommy Turrentine—the only one in his entire career. From his eponymous album, here‘s Tommy Turrentine and "Time‘s Up":

That same month Stanley waxed his own debut session for the same label, but it wouldn‘t come out until 1963. A few months later he made a date for Blue Note that was released soon after, enlisting, as had his brother, his Pittsburgh friend Horace Parlan on piano. Parlan brought along bassist George Tucker and drummer Al Harewood; the three of them had formed a dynamic rhythm section for saxophonist Lou Donaldson, and their in-the-pocket sound would anchor all of the Stanley Turrentine-Horace Parlan dates to follow. Turrentine was coming off sideman work with Jimmy Smith on what would prove to be two of the organist‘s most popular Blue Note albums, Back At The Chicken Shack and Midnight Special. Looking back on Turrentine‘s Blue Note debut nearly 50 years later, Bob Blumenthal wrote that

"Few of his contemporaries were as adept at blending a taste for offbeat material with a knack for enlivening melodies and sustaining grooves that satisfied a mass audience."

Here‘s Stanley Turrentine doing a composition of his that he had also recorded with Jimmy Smith—"Minor Chant":

A month later this group was back in the studio for Blue Note with Tommy Turrentine added on trumpet for a Horace Parlan session. The subsequent album, Speakin' My Piece, included a Parlan composition that became a jazz standard and a signature theme for a number of radio shows, including Boston jazz DJ Steve Schwartz‘s long-running WGBH program, as well as being used in the hit French comedy Three Men And A Cradle. "Wadin‘" draws on Duke Ellington‘s "It Don‘t Mean A Thing If It Ain‘t Got That Swing" for inspiration and also evokes the church atmosphere of Parlan‘s childhood, transformed into a bluesy secular vibe circa 1960. Here‘s Horace Parlan and "Wadin‘":

Parlan and Turrentine appeared together on only five studio sessions and one live recording date in a 15-month stretch from January 1960 to March 1961, but the resulting albums provide some of the best examples of the Blue Note label sound at the zenith of its popularity. They were modernistic and accessible, soul-jazz hardbop records that didn‘t succumb to cliché. Blue Note was a busy label in these years, and a number of the sessions it recorded went unreleased for many years—sometimes because Blue Note producer Alfred Lion felt they fell short of his and the artists‘ creative standards, sometimes because of marketplace strategies and a wealth of product. At the end of 1960 Stanley and Thomas Turrentine did a session for Blue Note with the Parlan/George Tucker/Al Harewood rhythm section that Lion rejected as artistically unsuccessful; a few weeks later they returned to the studio and attempted much of the same material again, this time with better results. Still, the January session only emerged on record in 1978 as half of a double album called Jubilee Shout!, and then reappeared in 1987 as a standalone CD called Comin' Your Way. That it could sit in the vaults for so long is testimony to how high Alfred Lion was setting the bar for Blue Note in the early 1960s. It also featured another composition from Tommy Turrentine, whose strength as a composer has often been overlooked. Here‘s Stanley Turrentine doing his brother‘s "Thomasville":

Not long after the session, this musically simpatico group played a gig at Minton‘s, the legendary club on West 118th Street in Harlem that had helped give birth to bebop in the 1940s, and which was now called the Play House, where Tucker was frequently serving as leader of the house band. A key guest joined them—guitarist Grant Green, who was just beginning to make a name for himself, and whose rhythmic, bluesy lope fit right into the Parlan/Turrentine sound. Blue Note Records was there to record the gig, and producer Alfred Lion recalled that it was a packed room on a Thursday night, with "everyone in the best of spirits." As liner note writer Leonard Feather observed, the following track demonstrates what he calls Stanley Turrentine‘s "blend of qualities—the Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane-like sense of time and articulation with a tonal warmth often reminiscent of Lucky Thompson." From Up At Minton's, here‘s Stanley Turrentine and "Yesterdays":

Stanley Turrentine continued to record for Blue Note for much of the 1960s, but he forged his primary musical—and personal—partnership with organist Shirley Scott, while Horace Parlan made several albums with multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan Roland Kirk in the mid-1960s and eventually moved to Denmark, where he formed another vital musical collaboration with saxophonist Archie Shepp in a series of recordings done for the Steeplechase label. Turrentine and Parlan entered the studio together for the last time on March 18, 1961, to make Parlan‘s Blue Note album On The Spur Of The Moment. In only 15 months these two musicians from Pittsburgh created a musical legacy that serves as an enduring testament to the most soulful corners of the Blue Note sound‘s foundation. From that final session, here‘s Horace Parlan and "Pyramid":

Special thanks to Chuck Nessa.