In the late 1940s jazz impresario Norman Granz decided to produce a forerunner of the modern box-set that documented the current jazz scene, a folio of six 78 records illustrated with photographs of the artists and accompanied by liner notes for each of the musical selections. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear music from one of the very first jazz anthologies, performed by Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Lester Young, Ralph Burns, Coleman Hawkins, and others.

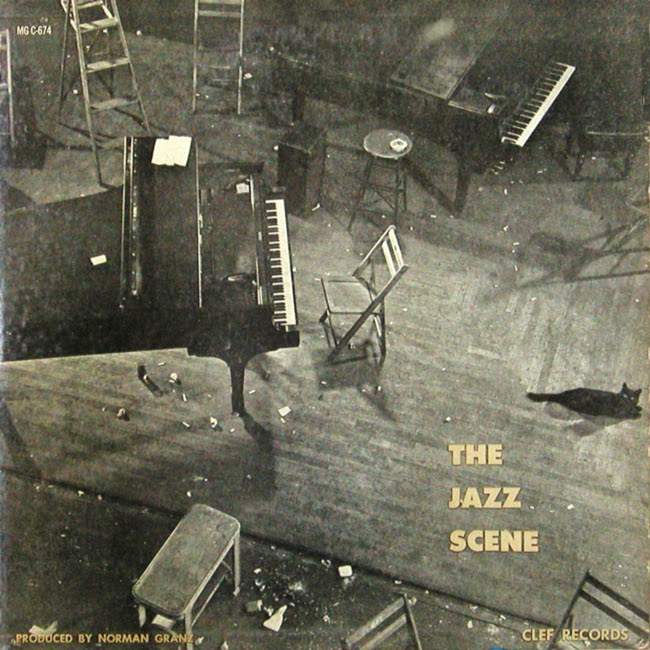

Granz, who had begun to present his Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts just a few years before, and who started the label that came to be known as Verve, wrote in his introductory note that "This is our attempt to present today‘s jazz scene in terms of the visual, the written word, and the auditory," and described how he‘d given the set‘s musicians complete artistic freedom to record their tracks as they saw fit. The photographs were taken by Gjon Mili, who had directed the legendary short jazz film "Jammin‘ the Blues," and the cover was illustrated by David Stone Martin, whose elaborate line technique sketches would adorn many a Granz-produced LP in the years to come.

The collection came out as a limited-edition set of 5,000 copies, in a 12-inch format usually reserved for European classical music, and it was priced at a cool $25-more money, by either the standards of 1949 or today, then it costs to find a used set of the expanded two-CD 1994 reissue online. Downbeat writer Michael Levin praised it when it was released as "the most remarkable record album ever issued," and it certainly seems like a model for some present-day record company marketing approaches, such as Mosaic Records‘ historical jazz sets. Initially Granz hoped to release more volumes of The Jazz Scene, but they failed to materialize.

As jazz writer Brian Priestly points out in his essay for the 1994 reissue, major labels had put out such sets for individual artists before, including Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong in the early 1940s, but Granz‘s anthology was a no-holds-barred effort to illuminate the exciting world of modern jazz in the late 1940s, when bebop, small-group-swing, and big-band music were all flourishing. To do so he commissioned recordings from musicians both young and established, although contractual restrictions prevented him from securing the work of some of his favorite artists, such as Ella Fitzgerald and Art Tatum.

We‘ll start off with two Duke Ellington compositions that resulted from Granz‘s initially approaching Harry Carney, Duke‘s baritone saxophonist. Carney was so enthusiastic that he pulled Ellington into the project; although Duke does not appear on the dates, he was in the studio directing Carney and an Ellingtonian rhythm section that included Billy Strayhorn on piano. These tracks stand out in particular for Duke‘s use of a string quintet, and they are rarely-heard works from the Ellington oeuvre:

Music now from THE two great tenor saxophonists of the era that Granz‘s Jazz Scene was attempting to capture-Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins, who were as influential and respected as Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane would be 10 to 15 years later. Young‘s contribution to the date was the earliest-recorded side for Granz's anthology, an uptempo trio affair with Buddy Rich on drums and Nat King Cole (who, for contractual reasons, was identified only as "Aye Guy" in the original liner notes) on piano, while Hawkins‘ "Picasso" was a solo tour de force. Each would work frequently for Granz in the years to come, both as Jazz at the Philharmonic tour members and as recording artists. Young recorded his contribution in one take; Hawkins sweated over his for a cumulative total of eight hours. Granz praised Hawkins especially in his liner notes, and his remarks throughout the booklet show that some of his ambition for the set was to elevate the stature of jazz in general:

One of the most exciting writing talents on the late 1940s jazz scene was pianist Ralph Burns, who wrote for Woody Herman‘s big band; he‘s perhaps best known for authoring "Summer Sequence" which led to the Stan Getz vehicle "Early Autumn." He was one of the first people Granz approached for the project, and his contribution featured several Herman band members, including trombonist Bill Harris and the lost-legend trumpeter Sonny Berman. As Brian Priestley observes in his essay for the 1994 reissue of The Jazz Scene, "The delicate tone colors, and the discreet way the opening waltz theme moves into 4/4, are indicative of the mastery that Burns brought to subsequent projects":

Another young arranger, George Handy, contributed a piece to The Jazz Scene. Handy was much admired by Burns, according to Jazz Scene reissue essayist Brian Priestley, and The Encyclopedia Of Jazz referred to him as "The most-talked-about new arranger of the day." He was known chiefly for the challenging scores he‘d penned for Boyd Raeburn, who led one of the most progressive big bands of the late 1940s. Handy battled health problems, including drug addiction, and was never able to realize the potential that he demonstrated early on. His response to Granz‘s request for some biographical notes was terse and rather testy, including remarks such as "Studied for awhile with Aaron Copland, which did neither of us any good," and concluded with "The only thing worthwhile in my life is my wife Flo and my boy. The rest stinks, including the music biz and all connected." So it‘s probably safe to say that Handy was feeling a bit disillusioned around this time. His contribution to The Jazz Scene, "The Bloos," drew on many members of the Raeburn orchestra and is a satire on the blues.

New Discoveries, An Expanded Version

When Verve‘s staff set about reissuing this Norman Granz project in the early 1990s, they turned up some previously unknown material-two Billy Strayhorn solo piano tracks that were evidently recorded for The Jazz Scene as well. Jazz writer Brian Priestley speculates that they were probably dropped because Granz ended up including both of the Harry Carney/Duke Ellington sides that had been recorded. In 1994, when The Jazz Scene was reissued as a two-CD set, Verve was able to include a great deal of extra material, including alternate takes, contemporaneous sessions by some of the artists involved, and new discoveries such as the Strayhorn selections. We‘ll also hear from alto saxophonist Willie Smith, who‘d been a key member of Jimmy Lunceford‘s big band, and who‘d go on to work with Duke Ellington himself after Johnny Hodge‘s departure from the Ellington orchestra, doing a classic Ellington composition.

The Jazz Scene, as an attempt to reflect the contemporary jazz world of the late 1940s, also included two of the leading lights of bebop--alto saxophonist Charlie Parker and pianist Bud Powell--and featured a contribution from bandleader Machito, whose orchestra was helping to forge and popularize Latin jazz, another development in 1940s music. This edition of Night Lights concludes with recordings from all three artists: a cameo appearance by Parker for arranger Neil Hefti, who would go on to become strongly associated with the post-1950 sound of Count Basie; a trio performance of the bop anthem "Cherokee" by Powell; and Machito‘s "Tanga," which, like Dizzy Gillespie‘s "Manteca," was a Spanish slang term for marijuana: