Before Nat King Cole established himself as an iconic vocalist, he was a superlative jazz pianist much admired by his peers who recorded and performed with Lester Young, Les Paul, Charlie Parker, and other notable colleagues, in addition to his own trio work. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear some of those recordings as we explore the artistry and love in Cole‘s relationship with jazz.

Nat King Cole is known and loved today for the numerous classic vocal recordings that he made throughout his career: "Stardust," "Unforgettable," "Nature Boy," "The Christmas Song," and many more. But when Cole started out in the late 1930s, he thought of himself as a jazz pianist, and singing came as an afterthought, though it emerged early in the career of what came to be known as the Nat King Cole Trio--a swinging configuration of piano, guitar and bass and unison vocals that eventually morphed into a unit where Cole took the spotlight as primary singer--the role in which he‘d find his greatest fame. It wasn‘t a singer, though, but a pianist who made a deep impression on the young Nat King Cole, who was born on March 17, 1919 and grew up in Chicago. In 1957 he told DownBeat writer John Tynan that Earl Hines had been a key early role model:

It was his driving force that appealed to me. I first heard Hines in Chicago when I was a kid. He was regarded as the Louis Armstrong of piano players. His was a new, revolutionary kind of playing because he broke away from the eastern style. He broke that barrier, the barrier of what we called ‘stride piano,‘ where the left hand kept up a steady striding pattern. Of course, I was just a kid and coming up, but I latched onto that new Hines style. Guess I still show the influence today.

In addition to Hines, Cole also had clearly listened closely to pianists such as Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum--but within a few years it was Cole himself who was serving as a source of influence to other, younger pianists. Pianist Bill Charlap has described Cole as "essentially a linear player (as opposed to a harmonic one)" but goes on to say that Cole‘s "linear language was a lot more streamlined and closer to the modern era" than his forebears Hines, Wilson and Tatum. "When I hear Nat," Charlap says, I hear foreshadowings especially of Oscar Peterson and the whole Detroit school, especially Tommy Flanagan and Hank Jones." As jazz critic Dan Morgenstern pointed out, you can hear how Cole influenced Peterson even in the short solo from this 1946 recording that Cole made under a pseudonym for the Keynote label:

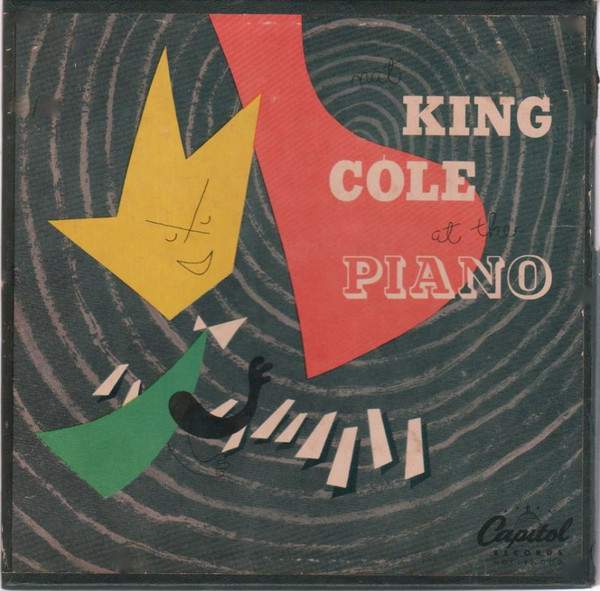

Nat King Cole was billed as "Lord Calvert" for that session, because he was under contract at the time to Capitol Records, where his trio had found its greatest success. They had had their first hit at the beginning of the 1940s for the Decca label with "Sweet Lorraine," but the association with Capitol that began in late 1943 vaulted them repeatedly into the charts over the next few years--and it‘s where we hear Nat King Cole as a jazz pianist in full flower, whether the recordings were instrumental or featured him on vocals as well. Here‘s music from their very first session for the label:

Another piece recorded at this session, "Straighten Up And Fly Right," became a huge hit and helped launch the trio into stardom. Their run of recordings for Capitol in the next several years would make them one of the most popular acts of the decade, and as their hits often featured Cole in a vocal role, the seeds of the trio‘s eventual demise were planted. At the same time, Cole occasionally made live appearances and recording dates that featured him in a jazz setting and that gave listeners the opportunity to hear his dazzling instrumental talent in full flight. Here‘s from the very first Jazz at the Philharmonic concert on July 2, 1944 is a performance of "Tea For Two," featuring Nat King Cole on piano:

But Cole and his cohorts were just getting started that day. Listen to this performance, simply titled "Blues" upon its release, that features Cole and guitarist Les Paul in an extended and increasingly kinetic musical conversation:

Although Cole always kept pace with and often outshone his jazz star colleagues in such settings, his primary vehicle throughout the 1940s continued to be the trio, though guitarist Oscar Moore and bassist Johnny Miller eventually left and were replaced respectively by Irving Ashby and Joe Comfort. On January 17, 1944, the Cole-Moore-Miller trio made what‘s proven to be a historic recording date of instrumentals, including a version of Rachmaninoff‘s "Prelude In C Sharp Minor" that‘s now considered to be a forerunner of the Third Stream movement in jazz, and a rendering of "Body and Soul" that would become a fixture in Cole‘s repertoire. This session alone would be enough to earn Cole a place in the annals of jazz-pian history. Decades later, reviewing a box-set reissue of the Cole trio‘s Capitol recordings, critic Gary Giddins wrote,

A few aspects of Cole‘s musicianship are immediately evident: the astonishing independence of voice and piano, for one--he rarely settles for mere pacing chords, preferring octaves and chromatic bass lines and subtly configured harmonies that complement and deepen the vocal interpretation. Then there is his wit and speed, lightning reflexes that hardly ever call attention to his technique but constantly spice his solos, interludes, intros, and codas. Then there is his lucidity and swing: on practically every one of those relatively rare occasions in which he performed with major jazz soloists, he stole the limelight. His solos are melodically sure, often sounding through-composed. His famous quote-heavy version of ‘Body and Soul,‘ of which there are several versions, is a spectacle of compression and relaxation… He had an individual sound on the piano, and a rare ability to shade that sound to the setting.

From that January 1944 date, here‘s a hard-swinging version of music from another Cole, Cole Porter--"What Is This Thing Called Love":

The Nat King Cole Trio performing "Body And Soul" and "What Is This Thing Called Love" before that, both recorded in 1944, with Oscar Moore on guitar and Johnny Miller on bass. Here's Cole on an all-star 1945 jazz date saxophonists Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter, as well as a young Max Roach on drums:

Throughout the early course of his career it was not unusual for Cole to record and perform with jazz artists outside of the trio; he was on the young Dexter Gordon‘s first-ever recording date as a leader, showed up on several magazine all-star jam session dates, and participated in two landmark sessions with saxophonist Lester Young, whose cool, fluid and inventive style was in some ways not that far removed from Cole‘s approach. Around the time of his second recording date with Young, Cole and his trio mates also featured in a broadcast with trailblazing bebop saxophonist Charlie Parker. We‘ll hear Cole now with both of these saxophone titans-and the drummer on both of these tracks, by the way, is the iconic Buddy Rich, who finds a great rhythmic sympathy with Cole in particular on Lester Young‘s "Somebody Loves Me":

Throughout the late 1940s Cole continued to garner recognition as a pianist, winning Esquire‘s poll for that category in 1946 and ‘47, and taking it as well in Metronome‘s poll for three years in a row, from 1947 to 1949. But his prominence as a vocalist continued to grow as well, fueled by hits such as "The Christmas Song," "Nature Boy," and "Mona Lisa." By the beginning of the 1950s, the trio was a fading presence in the Cole discography, rarely recorded in isolation anymore, heard, when it was heard at all, only in the context of a larger-ensemble setting, and in 1951 Cole announced its official disbandment.

Jazz-oriented Cole fans expressed disgruntlement over the changed proportions in his music, and perhaps Cole felt some dissatisfaction as well; in 1952 he began a run of three LPs that eventually form a kind of return-to-jazz trilogy, putting out a trio-oriented album called Penthouse Serenade, which the Capitol label would expand with further, similar recordings two years later. In January 1953, not long after the initial release of Penthouse Serenade, DownBeat ran an article titled "The Real Reason Nat Cole Cut His Piano-Only Album," in which Cole said,

Everybody seems to have forgotten about my piano. Just as they forget that Billy Eckstine was a pretty fair musician and bandleader, people think I‘ve always been a vocalist. The young kids more than anyone else, they‘re even surprised that I play a piano at all… all they‘ve ever heard me do is sing with big bands and strings in the background.

Cole went on to say,"People who know me know I‘ll never leave jazz. My roots are in jazz and that‘s the music I love. But I can please a lot of people with other kinds of music and also throw in some jazz--and they like it because they‘ve accepted me as a popular performer."

Nat King Cole and "I Never Knew," from his album The Piano Style Of Nat King Cole, recorded in 1955 with arranger Nelson Riddle. Cole before that doing "Don‘t Blame Me," recorded around the same time for an expanded version of his album Penthouse Serenade.

Cole retained a wry viewpoint about his singer-eclipsing-the-pianist dilemma; in November 1955 he said, "I‘ve been doing some thinking about this piano thing and you know something? At the start, when I was playing piano a lot, no one thought that I was so much. But now that I sing more, why, everyone says, ‘Gee, that Nat Cole used to play great piano.‘" The following year he completed what ended up being his back-to-the-piano trilogy with the album After Midnight, consisting of a series of quartet sessions complemented by a rotation of guest jazz artists, including saxophonist Willie Smith, violinist Stuff Smith, trumpeter Harry Sweets Edison, and trombonist Juan Tizol. Cole sang on all of the tracks, but the jazz intentions of the album were clear, and it‘s now considered a classic in the Cole discography:

Following After Midnight, Cole would never again revisit the piano aspect of his artistry with such force, though he did play on some of the albums The Nat King Cole Story and Let's Face The Music. He remained a vocal star till his death in 1965 at the age of 45, and that‘s how he was primarily remembered in ensuing decades, until reissues of his early recordings in the late 1980s and early 1990s began to raise his historical profile as an important jazz pianist. In 1952 Cole had said, "My heart is still with jazz;" and so, in considerable part, is his legacy today. I‘ll close with a 1943 recording that brings together Cole‘s remarkable talent as both a singer and a pianist: