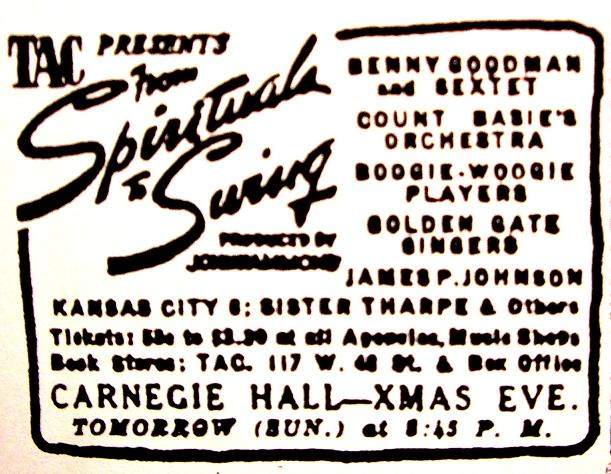

At the end of the 1930s, with America still emerging from the Great Depression and a second world war at hand, jazz impresario John Hammond organized a pair of concerts that showcased what he called "the music that nobody knows"-African-American blues, gospel, and jazz, presented to an integrated audience at one of New York City‘s most prestigious concert halls, featuring artists such as Count Basie, James P. Johnson, and Benny Goodman.

Trouble Finding Sponsors

Hammond was a talent scout and record producer who over the course of his career "discovered"--or at least brought into the limelight--artists ranging from Billie Holiday and Count Basie to Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. In 1938 he hit upon the idea of hosting a program of African-American music in New York City‘s Carnegie Hall, featuring some of the top blues, gospel, and modern jazz performers of the day. He titled the program "From Spirituals to Swing."

A few months earlier, in January, Benny Goodman had given the first-ever jazz concert at Carnegie Hall, with members of Count Basie and Duke Ellington‘s bands performing as well. At From Spirituals to Swing, however, all of the musicians were African-American, and because they would be playing in front of an integrated audience, Hammond had a difficult time finding sponsors for the concert. Even the NAACP turned him down!

"For The Folks And Not The Fat-cats"

Hammond finally turned to the New York-based New Masses, the Communist Party‘s journal of culture. New Masses‘ contributors at the time included authors Upton Sinclair and Richard Wright, as well as literary critic Granville Hicks and Hammond himself. In the concert‘s original program notes New Masses described itself as

for the folks and not the fat-cats; the New Deal and not the Nazis; labor instead of the Liberty League; and jobs instead of jaw music.

In the same program, Hammond and New Masses contributor James Dugan included a prologue called "The Music That Nobody Knows" which began,

The music that will be presented in New Masses‘ From Spirituals to Swing program is rarely heard. To be sure, it is not rare, for America is rich with it, but serious authors have neglected it, and it has had to find its followers among uncritical groups. American Negro music has thrived in an atmosphere of detraction, oppression, distortion, and unreflective enthusiasm.

The writers noted that many of the performers were making their first-ever appearance before a predominantly white audience, made a plea for an attitude of "informality and interest," and concluded, "May we ask that you forget you are in Carnegie Hall?" Night Lights is asking you now to imagine for the next hour that you‘re in Carnegie Hall, and that the Count Basie band has just taken the stage.