From the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s a five-story building in the heart of Manhattan served as a gathering place for jazz musicians and other artists, anchored by an iconic photographer devoted to his work. The photographer was W. Eugene Smith, and on this edition of Night Lights I'll talk with Sam Stephenson, author of both The Jazz Loft Project and the biography Gene Smith's Sink: A Wide-Angle View, about Smith and the musicians such as Thelonious Monk, Sonny Clark, and Hall Overton who passed through the loft scene. We'll also hear some music and sounds from the loft itself.

"That Loft Was Really A Place Where He Felt At Home"

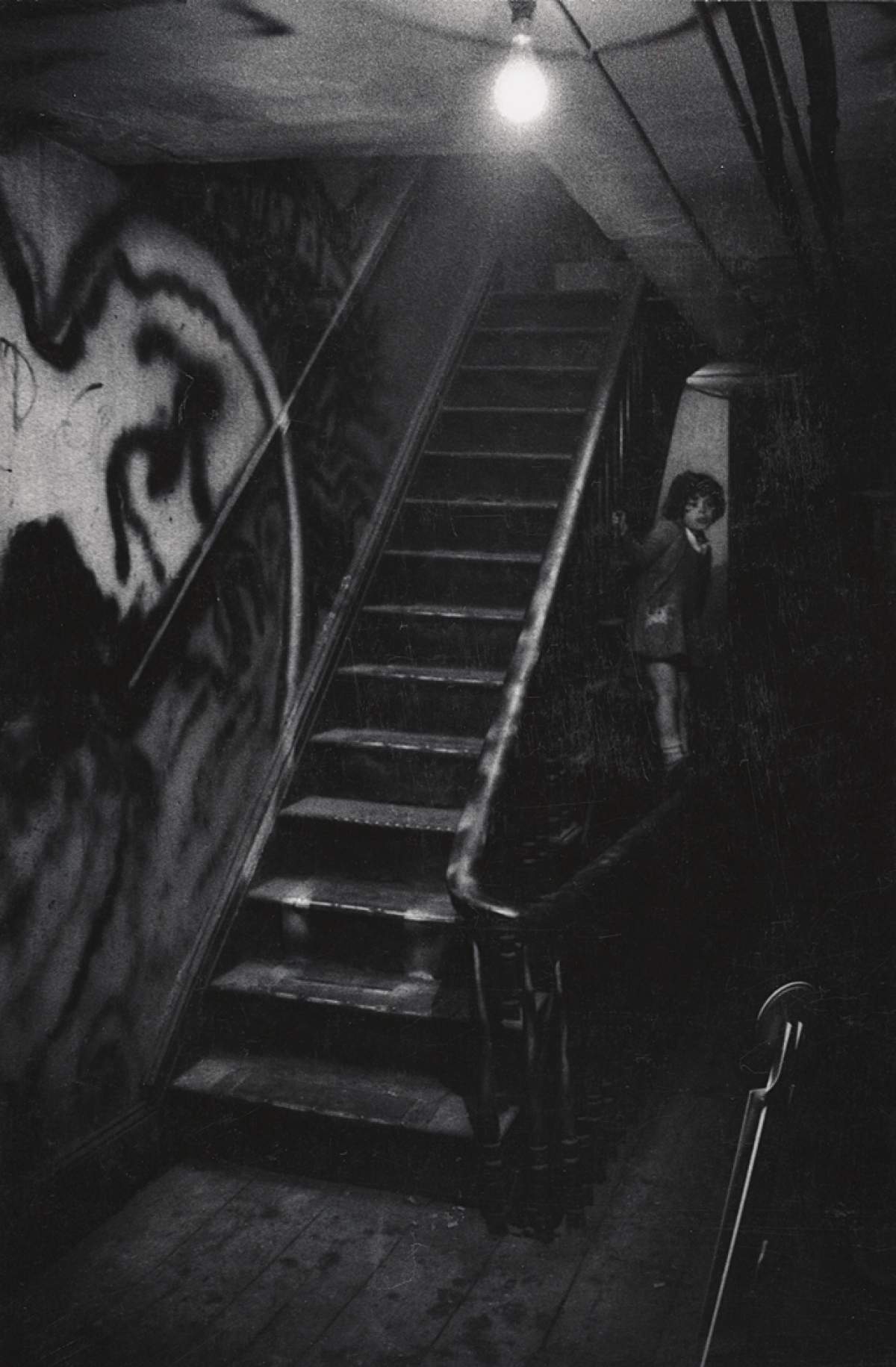

Imagine a place and time when jazz converged with literature, painting, and photography. A gritty, vibrant setting where Norman Mailer might breeze by to talk philosophy while Thelonious Monk prepares for a concert in another room. Maybe Bob Brookmeyer and Zoot Sims are jamming, or Salvador Dali‘s dropped in to help plan a happening. But urban street-life regulars are there as well, along with many other people drifting in and out whom you've never heard of. This is no sanitized and disconnected sanctum of sterility; it's a hive of creation amid rot, a microcosm of the human struggle to not only get by, but to say something about just what it is in which we're trying to get by.

There was such a place in New York City in the late 1950s and early 1960s, in a dilapidated five-story building at 821 W. Sixth Avenue. There painter David X. Young, musician Hall Overton, and photographer W. Eugene Smith all resided there during an artistically vital era of post-World War II America, pursuing their aesthetic vocations. Writer and researcher Sam Stephenson zeroed in on the story of Smith, bringing not only much of his previously-unseen work to light, but also the huge trove of recordings that Smith left behind from his years in the loft. He's put together two books of Smith's photographs of Pittsburgh, as well as a poetically comprehensive anthology of photos, transcripts, commentary, and interviews about the jazz loft, and with the publication of his 2017 biography, Gene Smith's Sink: A Wide-Angle View, he's finally reached the end of his W. Eugene Smith journey.

"When I started in 1997, it was a simple freelance article that I thought would be the end of it," Stephenson says. "The article came out in 1998, it got some attention, I spent some time in his archive, and one thing led to another... If you'd told me in 1997 that I was going to spend 20 years on (Smith), I would've said, 'You're crazy. There's no way!'"

Stephenson was pulled in by Smith's content, the enormous number of photographs he took (particularly of the city of Pittsburgh in the mid-1950s) and the wealth of recordings, amounting to 4500 hours, that Smith made at the loft building in New York City. "It was just like postwar urban field work of a certain kind," says Stephenson. "It was not who he was, really, but what he had done that drew me in and kept me focused for so long."

Smith was a brilliant and driven photographer who had already documented World War II in the Pacific and contributed a number of compelling photo essays to Life Magazine. But Stephenson says the initial motive for Smith's move into the loft in the mid-1950s came from desperation:

He was 38 years old, in the prime of his life, aesthetically and physically and intellectually. There's a lot of sadness to this story, a lot of melancholy… he left his family and moved into this loft. He was not made out to be a family man; he was just so dedicated and obsessed with his work. His work was really the only thing that he did. He needed a place to do it, and he moved into this dilapidated loft. He was trying to finish his Pittsburgh project. There were a bunch of jazz musicians hanging out there already, other artists.... these were people comfortable with oddity, obsession, late hours, everything that Smith did. That loft was really a place where he felt at home.

"A Place Of Craft And Work"

The loft, on West Sixth Avenue between 28th and 29th Street, was located in the heart of Manhattan's wholesale flower district, a key centrality that made it convenient for jazz musicians to stop by. There were also pianos at the loft. Thelonious Monk, Zoot Sims, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Roy Haynes, Bill Evans, Chick Corea, Sonny Clark, Don Cherry, Bob Brookmeyer, Mose Allison, and Lee Konitz were just some of the many jazz musicians who hung out, passed through, and played in the jazz loft. Smith and fellow loft resident and painter David X. Young recorded many of the jam sessions that took place there in the 1950s and 60s. But it wasn't just music that was caught on tape at the jazz loft; W. Eugene Smith recorded anything and everything, including numerous everyday conversations, as well as radio broadcasts of John F. Kennedy giving his first remarks as president-elect, Norman Mailer and other writers discussing civil rights, and Jason Robards reading from F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Crack-Up. "He had wires and microphones all over the place," says Stephenson.

Mailer was among the notable cultural figures who sometimes stopped by the loft, but Stephenson says the loft's function was not primarily as a hangout spot: "It was a place of craft and work." Some of the best evidence of that resides in the tapes of pianist Thelonious Monk and loft resident Hall Overton working over Monk's music with other musicians in advance of a February 1959 concert at New York City's Town Hall, a show that presented some of Monk's compositions in a tentet setting-a significant public moment for Monk.

Monk and Overton's extensive preparations for that concert are just one example of why Sam Stephenson describes the loft as "a place of craft and work." Along those lines, Stephenson says the photos that Smith took of jazz musicians at the loft put them in a different light than much other jazz photography of the time:

One of the problems with jazz photography in general is that it's severely iconographic. I think (Smith's) photographs of the musicians in the loft make them look much more human, much less like superheroes-and he also depicted the environment which is not Julliard, it's not a hallowed hall, it's a very difficult place where really hard work was being done.

"Most Of Them Were Just Stunned To Hear Themselves"

Hundreds of jazz musicians passed through the loft during the years that Smith lived there, some of them names that loom large in jazz history, others obscure or with small but devoted followings. One such artist was hardbop pianist Sonny Clark, who appeared on numerous dates as both sideman and leader for the Blue Note label in the late 1950s and early 1960s, before dying at the age of 31 in 1963 from a drug overdose. Clark had grown up in the Pittsburgh area, which helped spark Stephenson's interest in him, but it was his playing that sealed the deal for Stephenson's love. "The sound of his right hand on piano is one of my favorite sounds in all of jazz," he says. "His touch, when I hear it, I hear a really unique blend of heavy, sorrowful blues along with a buoyant swing":

Though Clark would enjoy one last outstanding spate of recordings with Blue Note beginning in late 1961, he was in bad shape during his time at the loft. "What I learned from the tapes was that he was really squatting in the loft in the summer of 1961," Stephenson says. "Smith would give him bottles to go return for their deposits... he was just so destitute, and a heroin junkie. He would play piano every now and then, and just hang around...there's one night when he almost dies, you can hear him overdosing; Smith was taping all this. It's a complicated story, it probably happened all the time, sadly, but rarely is a story like this documented in the way that Smith did on tape."

Clark was not the only musician among the loft regulars who struggled with a drug problem. Heroin, which had become a scourge on the jazz scene in the late 1940s, still had numerous artists in its grip, and kept some from reaching their full potential as professional artists. Drummer Ronnie Free, one of the loft's longest tenants, worked regularly as a part of the Mose Allison trio and in other musical settings, but his addiction eventually drove him to leave New York City. He is a prominent presence on Smith's loft recordings:

His story gets a lot of attention in my new book because I think it's such an important one. He was a brilliant drummer who'd dropped out of high school in Charleston, South Carolina and moved to New York. He had no trouble getting real high-quality gigs, but he had trouble keeping the jobs because of his drug addiction and his self-esteem. He kind of had stage fright. And in the loft, there was no stage. It was a much more private environment, and he excelled in that environment. He's on more than 200 hours of the loft tapes, sort of like the loft's house drummer. What's a miracle about that is that he was a very sensitive drummer, so he would adapt to the other musicians very easily. Ronnie Free was perfect (for the loft jams)

One of the recordings on which Free can be heard also captures pianist Paul Bley. I asked Stephenson what kinds of reactions he got when he interviewed musicians like Free and Bley decades later and played them recordings on which they appeared:

Most of them were just stunned to hear themselves. One of my favorite stories is about Paul Bley, who was recorded playing with Roland Kirk in the loft, among others. When I went to play these tapes for him, he cranked it as loud as it would go on his stereo. It was a summer day, and his windows were open, and he went outside and walked around the house. He just walked slowly around in the yard while he was listening to this music. I really didn't know what he thought about it. And then after a long time, he came back in and said, 'I'm really glad Eugene did this. This is stuff I really needed to hear, it's not a documented part of my career.

Some artists whom Stephenson played the tapes for decades later were not enthralled:

Others-Chick Corea, Jim Hall, Jeremy Steig... were mortified to hear that they had been recorded. Steve Reich, the great minimalist composer, was a student of Hall Overton's, and he was in the loft once a week for two years. One time he brought over a student string quartet from Julliard, and (Smith) recorded one of Steve's early quartets. I played that for him, and he was mortified! (laughs) He's a guy who I admire, almost a hero figure, but not somebody you want mad at you, and he said to me, 'I forbid you to ever play this in public.'

For all of the recordings like these that he made and all of the photographs that he took, W. Eugene Smith never put together a body of work about his time in the jazz loft, which he eventually left in the 1970s. He went on to produce other memorable pieces, however, especially his documentation of what mercury pollution had done to a fishing village in Japan. But his artistic and professional struggles increased, along with his ambitions, a deadly combination when it came to completing projects founded in such comprehensive documentation:

He became more damaged, he was more desperate, he was more addicted to alcohol and amphetamines, he was more paranoid... there were so many things going on that kept him from being able to make those decisions.

The irony is not lost on Stephenson that in approaching the mountain of material Smith left behind, he himself ultimately opted in his biography of Smith to use a very different method to complete his work:

Somewhere along the line I realized that you can get a clearer picture of something or a person if you look off to the side of it. If you look at stars or planets in the sky at night, a lot of times you can see them clearer if you look off to the side. I began to realize that all these interviews I'd done (with others) about him, all the research I'd done that seemed like a side door to Smith, or a tangent, or a digression, it was all a reflection of him in a way. It started to feel like a constellation that I was building around him.

"Do Something That Nobody Else Is Going To Do"

If one quote could come close to summing up W. Eugene Smith's life, it might be a line from Lord Byron that Smith can be heard quoting on one of the loft tapes: "There's music in all things, if men had ears." Smith died in 1978 at the age of 59. His belongings, totaling thousands of photographs, recordings, and other material, sat in an archive in Arizona for 20 years, until Sam Stephenson began digging into them. With bountiful assistance from the Reva and David Logan Foundation, Stephenson was able to devote himself and enlist others to reconstruct a seemingly lost world of mid-20th century American art, in a way that gives us as close to a visceral sense as we're ever going to get of what the process of creation was really like for one individual and the people around him. That was only possible, of course, because Smith left so much raw material to explore, in addition to the photographs that he so painstakingly worked on.

That work led Sam Stephenson to the stories of many other people that he documents in his biography of Smith, to a deeper and broader understanding of human experience brought about by putting together the mosaic of a life, a life that like any other is not just one individual, but the sum of that individual's interactions with so many other individuals. There's melancholy to be sure that the world as we know it is passing away at every single moment—sometimes in large ways, as in the loss of a loved one, more often in the most glacial and undetectable of manners. But we can make small monuments of our time here, whether it's a garden or a work of art or the love of other beings, and through making life more meaningful to ourselves, make it more meaningful to others as well. "Do something that nobody else is going to do," Stephenson says. "That's what Smith did."

Jazz Loft Annex

- Gene Smith's Sink: A Wide-Angle View (Sam Stephenson's new biography)

- The Jazz Loft Project (Stephenson's previous book about Smith and the loft)

- The Jazz Loft Project (website)

- Thelonious Monk, The Thelonious Monk Orchestra At Town Hall

- Clark's Last Leap: Sonny Clark, 1961-62 (previous Night Lights show)

Special thanks to Sam Stephenson and Casey Zakin. Photographs courtesy of the W. Eugene Smith Archives.