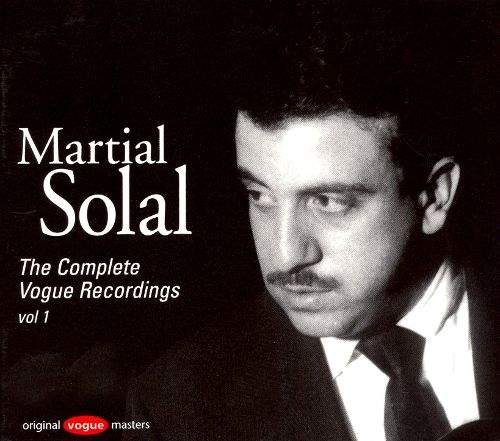

In the 1950s the young French Algerian pianist Martial Solal emerged on the European jazz scene, playing with Sidney Bechet, Lucky Thompson, and Django Reinhardt and establishing himself as one of the continent's brightest jazz stars. On this edition of Night Lights we'll hear recordings that he made with all of those artists, as well as many under his own name in solo, trio, and larger ensemble settings, and some of his film music as well.

Solal came of musical age in the mid-20th century European jazz scene, launching a career that stretched into the 21st century and made him one of the most respected jazz improvisers in the world. Born in Algiers on August 23, 1927, he played music halls across French North Africa as a teenager before moving to Paris at the beginning of the 1950s. "Paris was very bad for me," he told Martin Williams in 1963. "I knew nobody. I had to wait about three months without speaking to anyone. I did not know where the streets were." He also felt that he did not yet have the technique that he needed, as he described to Williams, "to play everything I hear in my mind."

Solal eventually found work with a popular band, practiced voraciously, and absorbed the modern sounds from America that European musicians were embracing. "Bebop is where it started with me and jazz," he told DownBeat writer Ted Panken in 2009:

I listened deeply to Bud Powell, but early I understood that to become unique, you can't listen and copy. I had masters in my mind, but I wanted to know everyone and forget them, so I could turn my back and start to be myself.

The sound Solal forged was both virtuosic and lyrical, and endlessly creative; jazz scholar Loren Schoenberg says he seemed incapable of playing a cliché. Tom Perchard, writing about Solal's 1950s and early 60s recordings, describes them as

stuffed full of fast flights of notes each one struck perfectly dead center, masses of intersecting lines, ceaseless harmonic invention… there is a complex yet utterly transparent logic to his direction and redirection of a phrase… to French listeners and writers of the 50s and 60s… Solal's power was spectacular.

Solal's debut on disc in 1953 proved to be a sort of passing of the torch; he was part of a group backing Django Reinhardt on what turned out to be the 43-year-old gypsy guitarist's final recording, with the track "Deccaphonie" providing a charged outburst of boppish modernism from Reinhardt just a few weeks before his death from a brain hemorrhage:

Solal crossed paths with other high-profile jazz musicians in the 1950s, including expatriate American drummer Kenny Clarke, who would go on to play frequently with Solal, as well as in a trio headed by one of Solal's musical inspirations, pianist Bud Powell. In 1956 Clarke made an album utilizing arrangements of Powell's friend and fellow Solal hero Thelonious Monk's compositions, done by French arranger and musical scholar Andre Hodeir. Solal's contributions to "Bemshaw Swing" stand out as an early highlight in his discography and give us a chance to hear one of Europe's greatest musical minds interacting with one of America's greatest jazz composers:

By that year Solal had made a number of dates under his own name as well, in trio, quartet, and solo settings. In Solal's playing one can hear traces of the pianists he had listened to and admired, such as Erroll Garner, Art Tatum, Fats Waller, and Bud Powell… but somehow Solal filtered these influences into a sound all his own:

In these early years Solal also teamed up with two American saxophonists who were spending time abroad—New Orleans legend Sidney Bechet, and the younger but much-respected Lucky Thompson. His empathetic dialogues with these two masters on American popular-song standards are a revelation of the ability he would demonstrate throughout his career for invigorating jazz repertoire with abundant dashes of harmonic and rhythmic creativity. They also exemplify Martin Williams' comment that "Solal's best playing invites one to deal with basics, and deal with them in a rather awed way."

At the end of the 1950s, Solal ventured into a new realm, writing and recording music for film, most famously for Jean-Luc Godard's 1959 movie A Bout de Souffle (known in English as Breathless), which stands as the ultimate statement of French New Wave cinema. Solal's music was a good match for Godard's style, as DownBeat writer Ted Panken has observed, noting that Godard's "use of the jump-cut is a visual analogy to Solal's penchant for making instant transitions in a piece."

Solal also wrote in mid-sized and large-ensemble settings for his own recordings in the late 1950s, a natural development of his orchestral-like conception for the piano. Here are two Solal compositions from 1958, with Pierre Michelot and Kenny Clarke again in the rhythm section:

Although Solal recorded most frequently in a trio, with forays into big band and mid-sized groups, his solo recordings are perhaps the best way to experience his considerable musical vocabulary and prowess. From his 1963 Capitol LP Viva La France! Viva Le Jazz! Viva Solal!, here's his solo rendition of Thelonious Monk's "Round Midnight":

That same year Solal made his American debut at the Newport Jazz Festival, brought there by festival promoter George Wein at the urging of Duke Ellington and Oscar Peterson, who had heard Solal in Europe. Solal was championed by American jazz critic Martin Williams, who called him "one of the best jazz pianists in the world" in a 1963 article introducing him to American audiences:

He is as natural a musician as was Sidney Bechet… not only can Solal swing, he swings with a vitality that is personal, and a sureness which allows him rhythmic variety and variation of a sort that many American jazzmen of his generation have not attempted. He has fine pianistic technique, but it reveals itself so soundly and so musically that one may be almost unaware of his proficiencies. He puts nearly every idea to a direct musical use, and time and again one notices Solal quietly employing effects which might easily be turned into blatant grandstanding by a less discreet and dedicated player. Above all, Solal answers the basic criterion: he invents interesting, fresh, and personal music.

Martial Solal in America, on Night Lights:

More Martial

- At Home In Paris With Pianist Martial Solal (NPR feature)