The inspiration came from a late-night party, a convergence of Hollywood glamour and nascent civil-rights activism with one of America's greatest jazz orchestras. In the summer of 1941, as Americans warily regarded a world war that seemed to be edging ever closer to their shores, Duke Ellington staged what he would later call "the first 'social significance' show," Jump for Joy. Jump for Joy was an all-black musical revue that Ellington said "would take Uncle Tom out of the theater and say things that would make the audience think." It featured the Ellington orchestra in its so-called "Blanton-Webster" years, playing at the peak of its powers, and up-and-coming African-American performers such as the actress Dorothy Dandridge, the blues singer Big Joe Turner, and the comedian Wonderful Smith. The poet Langston Hughes contributed a sketch entitled "Mad Scene From Woolworth's," and Ellington collaborator Billy Strayhorn took a significant hand in scoring the show.

Created and presented in Los Angeles, Jump for Joy had at its center and periphery a host of legendary Hollywood figures. The musical was financed in part by the actor John Garfield; its director, Nick Castle, went on to become a famous choreographer for 20th Century Fox. Charlie Chaplin stopped by rehearsals to give advice, Orson Welles offered to make the show a Mercury Theater production, and Mickey Rooney eagerly attempted to demonstrate his compositional talents by writing a song called "Cymbal Rockin' Sam" for Ellington's drummer Sonny Greer. Sid Kuller, who authored many of the revue's sketches and song lyrics, was a writer for MGM who had just knocked off The Big Store for the Marx Brothers.

Jump for Joy opened at the Mayan Theater on July 10, 1941 and ran for 122 performances, with the Ellington orchestra playing in the pit every night as African-American performers spoke, sang, danced, and joked in rebellion against traditional representations of blacks in movies and musical theater. In a bold break with convention, Ellington expressly forbade the 60-member cast to "blacken up," or artificially darken their skin hues. "The show was done on a highly intellectual level," he recalled in his 1973 memoir Music Is My Mistress. "No crying, no moaning, but entertaining, and with social demands as a potent spice. The Negroes always left proudly with their chests sticking out."

The show received mostly positive reviews, but the brash racial jubilation of songs such as "I've Got a Passport From Georgia" and "Uncle Tom's Cabin Is a Drive-In Now" provoked death threats, and one cast member was beaten as he left the theater. Although Ellington hoped to take the show to Broadway, its lack of stereotyping and its unabashed celebration of African-American pride made it an unlikely candidate for New York's Great White Way. After closing on September 29, 1941, it was revived for one week in November, and then again in Miami Beach in 1959 for an aborted two-week run. Although the musical has occasionally been recreated both onstage and in concert by others, and the original revue thoroughly documented by Ellington assistant Patricia Willard for a 1988 Smithsonian LP, Jump for Joy remains an important but often-overlooked chapter in the career of Duke Ellington. He later remarked that it paved the way for Black, Brown and Beige, his ambitious 1943 orchestral recreation of African-American history. It also served as an early salvo in the cultural struggle for equality. When a young San Francisco protester confronted Ellington in the early 1960s with the question, "When are you going to do your piece for civil rights?" Ellington replied, "I did my piece more than 20 years ago when I wrote Jump for Joy."

WFIU's Jump for Joy: Duke Ellington's Celebratory Musical features nearly all of the music that Ellington's 1941 Blanton-Webster band recorded for the show, including the classic hits "I Got It Bad (and That Ain't Good)," "Rocks In My Bed," and "Chocolate Shake." Other highlights include a portion of comedian Wonderful Smith's monologue, a radio medley spot, and Ellington himself discussing the musical and its impact, more than 20 years after its debut. Guests include Ellington assistant and Jump for Joy scholar Patricia Willard, Smithsonian Masterworks Orchestra conductor David Baker, Ellington biographer John Edward Hasse, cultural historian Michael McGerr, and poet Kevin Young, who recreates Ellington's 1941 Lincoln Day speech, "We, Too, Sing 'America'."

Duke Ellington once said that Jump for Joy "was the hippest thing we ever did." As Patricia Willard notes, it fulfilled his lifelong criteria for success: "doing the right thing, at the right time, in the right place, with the right people." In an age when the film and theater industries presented African-Americans primarily as servants and porters, as fearful and clowning stereotypes, Duke Ellington dared to produce and grace a musical with the same dignity, wit, beauty, and unabiding hipness that he always brought to his band. Jump for Joy is a cultural milestone and another example of how this great American composer traversed the racial and aesthetic boundaries of his time.

Suggestions for further reading:

Michael Denning, The Cultural Front (pgs. 309-319)

Duke Ellington, Music Is My Mistress

John Edward Hasse, Beyond Category: the Life and Genius of Duke Ellington

Stuart Nicholson, Reminiscing in Tempo (pgs. 231-235)

Klaus Stratemann, Duke Ellington Day By Day and Film By Film

Patricia Willard, "Jump for Joy" (essay for 1988 Smithsonian LP)

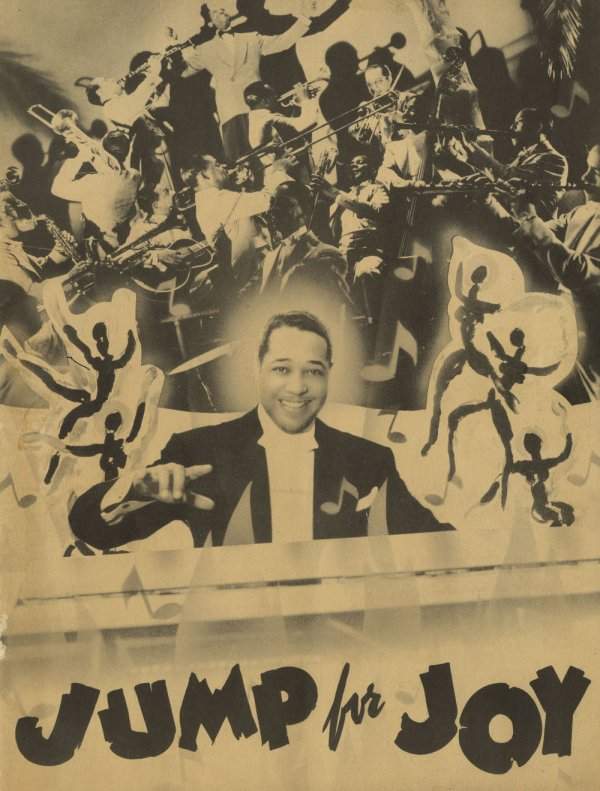

Photo of the Jump for Joy program provided by Patricia Willard. Special thanks to the Archives Center of the National Museum of American History.