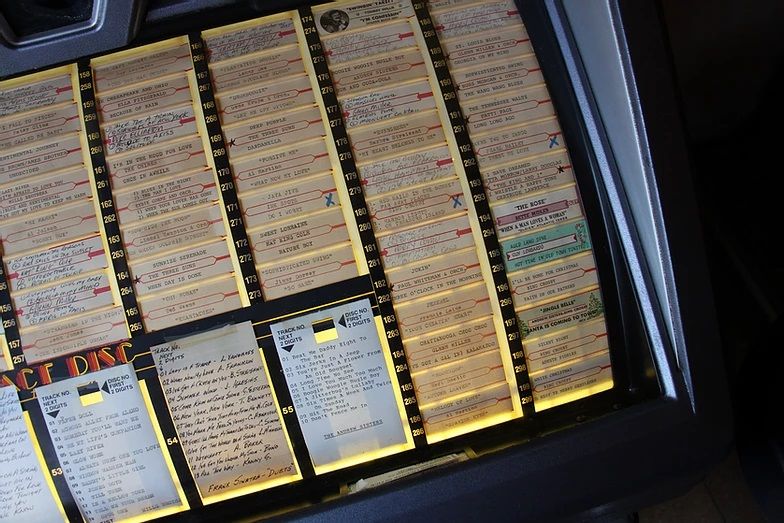

Once upon a time you could find many neighborhood bars with jukeboxes that featured numerous jazz recordings. (You still can at the Red Key Tavern in Indianapolis, where this jukebox resides.)

Long before Spotify and Pandora and other streaming services, before you could seemingly access almost all of the music in the world through a few keystrokes on a computer or cellphone, there were jukeboxes—the earliest method of delivering multiple musical options to a listener, who for a nickel, or later a dime, and eventually a quarter, could pop a coin into a slot and hear the record of his or her choice.

Though we think of jukeboxes as a mid-20th century phenomenon, coin-operated automatic sound-playing devices actually date all the way back to the end of the 1890s. But it’s true that jukeboxes didn’t really break out in a big way until the early 1930s, spurred on by the end of Prohibition, as legal bars and taverns burst into existence across America. Record sales, mired in a terrible slump since the onset of the Depression, began to gain again, aided in large part by the large-scale stock purchases of jukebox owners and operators. Some record companies even began subsidiary labels and encouraged their artists to make records aimed specifically for the growing jukebox market. One such artist, big-band leader Duke Ellington, utilized a number of highly-talented musicians from his orchestra to make small-group dates under their own names that catered to the emerging jukebox trade. In 1938 his alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges waxed a song that invoked Hodges’ nickname “Jeep” and became such a hit that it was associated with Hodges for the rest of his career.

Alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges performing “Jeep’s Blues,” a jukebox hit recorded in 1938 with a small group of musicians from the Duke Ellington orchestra, including Ellington himself on piano. Hodges would reprise “Jeep’s Blues” at Ellington’s legendary 1956 Newport concert in an attempt to calm an overly jubilant crowd after Paul Gonsalve’s epic 27-chorus saxophone solo on “Diminuendo and Crescendo In Blue.”

As was and would be the case in radio, sometimes the intended A side of a single found less favor on the jukeboxes than its flipside. One such notable instance occurred with Billie Holiday’s 1939 single “Strange Fruit,” a song that became an anti-lynching anthem, and which her record company had no interest in recording, giving her a pass to make it instead with the much smaller Commodore label. But though “Strange Fruit” was an immediate sensation and soon passed into popular culture legend, it was “Strange Fruit’s” companion song “Fine And Mellow,” written by Holiday, that became a hit in jukebox venues. In this next set we’ll also hear another iconic recording from 1939 that found favor on jukeboxes—saxophonist Coleman Hawkins’ “Body and Soul.” First, the flipside of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” that became a hit instead, though it has retained none of the historical significance of its shellac sibling:

By 1939, the year that those two records came out, there were an estimated several hundred thousand jukeboxes in place across America, in bars and taverns, diners and soda shops, and numerous other establishments. According to jazz scholar Eddy Determeyer, the boxes utiized 30 million records that year, and their success caused a national coin shortage.

As these music machines continued their dominant march into popular culture, there were even songs that referenced jukeboxes—one a hit for a bandleader whose records had enjoyed many spins across America in recent years when it was released in 1942. And it also invoked the day of the week that business surveys found to be most profitable for jukebox use.

Glenn Miller in 1942 with “Jukebox Saturday Night,” the last hit to chart for his civilian orchestra, with Miller off to the military to form what would become known as the Army Air Force band. Miller, like Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, and many other big band leaders benefitted from and offered public testimony to the impact of jukebox play on their careers.

The World War II years brought a temporary halt to new jukebox production, owing to wartime needs, though jukeboxes remained highly popular, and even found a new home in youth centers that were opened to counter the growing problem of juvenile delinquency. Jukeboxes also played a part in sparking the American Federation of Musicians' 1942-1944 recording ban. Union leader James C. Petrillo and others were concerned that jukeboxes (which also required no royalty payments), as well as radio and phonographs, were usurping live performance employment opportunities for musicians.

By the time the war ended in 1945, the big-band sound that had occupied prime place with youthful jukebox consumers began a slow fade in popularity, giving way to the rise of jump blues, R & B, and pop ballads. Bebop enjoyed a surge of attention as well. Many of the popular jukebox records of the late 1940s and early 50s, even if not defined as “jazz” per se, certainly had a jazzy sound. We’ll hear two such hit records in our next set, starting off with Johnny Otis’ “Harlem Nocturne":

Tenor saxophonist Gene Ammons performing “My Foolish Heart,” a recording made for the Chess label that singer Billie Holiday cited as one of her favorite records, and one that became a jukebox favorite, particularly on the South Side of Chess’ hometown Chicago. Johnny Otis and “Harlem Nocturne” before that, another jukebox favorite that also became frequent musical accompaniment for strippers, along with saxophonist Jimmy Forrest’s jukebox hit “Night Train.”

45 rpm records that were smaller and less breakable began to replace 78s as the 1950s began. Newly-manufactured jukeboxes around the same time also upped the number of records they could contain from two dozen to one hundred, giving users far more musical options. The term “jukebox,” by the way, stems from so-called “juke joints,” music venues that catered to African-Americans, especially in the south, and where one could find jukeboxes as well. The word “juke” may have been derived from a West African term that meant rowdy or disorderly. Industry reps in the late 1930s and early 40s had hated the term, preferring to call the machines “automatic phonographs,” but popular usage eventually made avoiding the jukebox moniker impossible.

Whatever one called them, they continued to be highly influential throughout the 1950s. Tommy LiPuma, an aspiring musician in those days who went on to become a renowned record producer and head of Verve Records, late in his life recalled a seminal jukebox experience:

In the 1950s the jukebox was the deal. As a saxophone player I was gigging, although still at school. I’d sit in with black musicians; the jukeboxes in ‘the hood’ were outrageous. One day I’m sitting there making myself scarce, because I was under-age, and suddenly out of the jukebox comes this record. It was ‘Just Friends’ by Charlie Parker, that first time I heard it I couldn’t believe it.

Here's what Tommy LiPuma heard:

With the advent of the 45 in the 1950s and its continuing success into the 1960s, singles made for jukebox and radio play began to be mixed with those outlets in mind. As jazz musician Jim Sangrey has noted, the mastering tended to be “loud and hot,” so that the music jumped out at you in a viscerally exciting way at the bar or in your car.

The iconic Blue Note jazz label certainly found value in aiming their product at this kind of market. Mosaic Records founder and former Blue Note employee Michael Cuscuna told me that “In the fifties, jukeboxes that carried jazz were very popular in urban areas. The fact that (Blue Note producer) Alfred Lion did sessions that were just for 45 releases underlines their profitability. Jukebox services paid for the single that they got from companies so there was money to be made. And the fact is that cuts from albums edited down or broken into parts one and two helped expose a lot of jazz and contributed to album sales. I often ran into jukeboxes as late as the early 1980s that still had John Coltrane’s Blue Train in them! This went on for quite a while. When I joined Atlantic in 1972, they we still issuing jazz singles. It was there that I learned that you could still sell 5000 jazz singles to jukebox operators and turn a profit out the door.”

We’ll hear a couple of Blue Note jukebox records now, starting off with Horace Silver, Bill Henderson, and “Senor Blues”:

Two edited 45s from the Blue Note label that were made with jukeboxes in mind—guitarist Kenny Burrell’s “Chittlins Con Carne” and before that, pianist Horace Silver joined by vocalist Bill Henderson on “Senor Blues.”

Prestige Records was another label that generated many jukebox-friendly singles, especially in the soul-jazz category that was popular in many African-American neighborhood venues that had jukeboxes. A 45 edit of organist Brother Jack McDuff’s smoking live performance of “Rock Candy” gives us a good taste of what could often be heard blaring from those bars and taverns. Prestige also scored big in the mid-1960s with organist Richard Groove Holmes’ 45-edit take of Erroll Garner’s “Misty”… we’ll hear it as well in this next set of Prestige soul-jazz jukebox hits:

Jazz writers and producers such as David Rosenthal and Bob Porter have attested to the widespread presence and popularity of jazz on jukeboxes in black neighborhoods throughout the 1950s and 60s, mixed in with R & B and blues and soul, and many records blurring the lines of these genres. But jazz records even showed up on jukeboxes in Communist bloc countries in Europe such as East Germany and Hungary, though Bulgaria did NOT join the party, blasting jazz as “corruptive and corrosive, a decadent Western influence that has no place in pure Communist life.” Presumably the Bulgarian apparatchiks would have found counted bossa-nova and R-&-B-influenced jazz particularly offensive. We’ll hear two popular 45 jukebox edits in this next set that reflect those musical trends of the early 1960s, starting off with Stan Getz, Astrud and Joao Gilberto, and “Quiet Nights Of Quiet Stars":

Organist Jimmy McGriff and “I’ve Got A Woman Pt. 1,” preceded by Stan Getz and Astrud and Joao Gilberto’s 45 edit version of “Quiet Nights Of Quiet Stars—two records you could have likely found on many jukeboxes in the early 1960s.

As the 1960s progressed, jukeboxes remained popular, but they began to face new challenges—perhaps foremost among them the sudden popularity of long-playing albums with younger listeners and buyers. Jukeboxes could not accommodate the LP. Jazz artists too began to expand their musical conceptions and experiments in ways that weren’t as 45-friendly. Still, in the late 1960s and early 70s you could walk into some bars and hear a classic jukebox edit with a soulful groove like this one—saxophonist Eddie Harris and “Listen Here":

By the mid-1970s, jukeboxes were considered by many in the trade to be in decline. Fast-food restaurants that were multiplying across the landscape were less inclined to have jukeboxes, and the long-running problem of bars and taverns catering to customers who preferred to watch sporting events on television continued. By 1974 Wurlitzer, once the biggest jukebox manufacturer of them all, had ceased production. Starting in 1978, jukeboxes were also no longer exempt from music royalty payments, as they had been since 1909. In the early 1990s a number of establishments converted from 45-playing jukeboxes to CD-playing ones, which finally made the album format accessible to jukebox listeners. Ultimately, though, jukeboxes became seen more as nostalgia items, charming pop-culture remnants of the mid-20th-century. Still, they set an early model for the now widespread concept of being able to sample and choose from a wide range of recordings, and they helped to promote the success of many jazz artists from the big-band era to the 1970s. I’ll close with a 45 edit of a popular 1973 recording by pianist Herbie Hancock, distilled from the 15-minute-long version that appeared on his breakthrough album Head Hunters:

MORE JUKEBOX JAZZ

Jazz For Mad Men: Hits From The 1960s (previous Night Lights program)