Singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell was at the peak of her commercial success in the mid-1970s when she began to take her music in a jazz-oriented direction, recording and performing with artists such as bassist Jaco Pastorius, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, and pianist Herbie Hancock. On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear some of those recordings and performances, as well as Mitchell‘s take on a vocalese classic and a later-period with-strings interpretation of one of her biggest hits.

In 1974 Joni Mitchell was 30 years old and riding high on the charts with Court and Spark, the Canadian-born singer-songwriter‘s sixth and most commercially successful album. From the late 1960s on she‘d built a following with folk-pop songs such as "Woodstock," "Both Sides Now," "Chelsea Morning," and "You Turn Me On I‘m A Radio," driven by her inventive, melodically-propulsive and uniquely-tuned guitar sound and her poetic tales of complicated love. But Mitchell was on the verge of taking her music in a jazz-influenced direction over the next five years that would disappoint or mystify much of her audience and divide critics, though the albums that resulted are now seen as some of her finest artistic statements.

Mitchell had grown up loving jazz albums and artists such as Miles Davis‘ Sketches Of Spain and the vocalese group Lambert, Hendricks, and Ross, and when she went out on the road in 1974, she hired Tom Scott‘s L.A. Express jazz band, members of which had played on Court And Spark, to back her. Mitchell had chosen to end her blockbuster album with a song that was a jazz vocalese staple of the 1950s, and that seemed out of place to some-but in retrospect, it was pointing the way forward. We‘ll also hear the title track, a lament about upward mobility, from Mitchell‘s 1975 followup, The Hissing Of Summer Lawns, an album that met with a mixed reception and more shades of the jazz influences to come. First, here‘s Joni Mitchell performing Annie Ross and Wardell Gray‘s satirical hipster ode to psychoanalysis "Twisted":

In 1976 a key figure emerged in Joni Mitchell‘s jazz period. Jaco Pastorious was a young, charismatic and transcendentally-inventive bassist whose debut LP a year before had grabbed the ears of many jazz listeners with his fretless and highly-melodic, singing and expansive bass style. His harmonics and soaring, arcing, elongated tones and lines were a good fit for the pacing of Mitchell‘s songs, where a rush of words could suddenly arrive at a suggestion of newly-opened space, or spiral down to earth from the compression of her narrative. Pastorious‘ strong presence would inhabit all of Mitchell‘s subsequent late-1970s albums, and he would bring other members of Weather Report, the immensely-popular jazz-fusion group that he had just joined, into Mitchell‘s orbit as well.

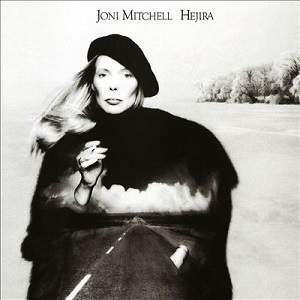

We first hear Pastorius with Mitchell on her 1976 album Hejira, which signaled the songwriter‘s growing embrace of jazz, some of it written while she was touring with Bob Dylan and Joan Baez‘s Rolling Thunder Revue. The title track also featured clarinetist Abe Most, who had played with the big bands of Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman; you‘ll hear him enter at a very appropriate moment in the song:

Hejira went gold but failed to generate any radio hits. This did not deter Mitchell from pushing her music even farther into new territory; her 1977 followup, Don Juan's Reckless Daughter, was a double LP with several experimental tracks including "Paprika Plains," a sixteen-minute-long orchestral recording with a piano part improvised by Mitchell. Jaco Pastorius was back and brought Wayne Shorter from Weather Report with him, as well as several of the group‘s former or current percussionists. One reviewer called the resulting album "ambitious as hell, a double-record of staggering depth, complexity and musical scope from one of the most talented artists working in pop music… there is so much on this record it‘s going to take months, perhaps even years, to absorb it all." From Don Juan's Reckless Daughter, here‘s Joni Mitchell and "Jericho":

Mitchell took her interest in jazz to new heights in 1979 with the album Mingus. The year before Charles Mingus, in declining health as he battled ALS, had reached out to Mitchell after hearing the 16-minute-long track "Paprika Plains" on Don Juan's Reckless Daughter. Mingus‘ original concept for their collaboration centered around setting T.S. Eliot‘s Four Quartets to music, but Mitchell found it a less-than-inspiring idea to execute. Instead Mingus, now confined to a wheelchair, gave Mitchell some melodies he‘d written by humming them into a tape recorder. He also asked her to set his ode to Lester Young, "Goodbye Porkpie Hat," to words as well. Mitchell brought Jaco Pastorius, Wayne Shorter and Don Alias back for the studio sessions, as well as Weather Report drummer Peter Erskine and pianist Herbie Hancock.

Charles Mingus died in January of 1979 at the age of 56, while work on the album was underway; some of the melodies, such as "God Must Be A Boogie Man," were written by Mitchell after his passing. The Mingus album, released six months later, was preceded by a DownBeat cover story on Mitchell in which she talked about her early love of jazz and how the collaboration with Mingus had come about. She also went out on the road for the first time in three years with a band that included Pastorius, saxophonist Michael Brecker, guitarist Pat Metheny, and keyboardist Lyle Mays. We‘ll hear that band live doing Mitchell‘s lyrics-added version of Mingus‘ "Goodbye Porkpie Hat;" from the album Mingus, here‘s "The Dry Cleaner From Des Moines":

Mingus did not fare well either commercially or with rock critics, although it garnered some sympathetic and favorable reviews from jazz writers, and proved to be the last album made for Asylum Records by Mitchell , who followed Asylum‘s founder, David Geffen, to his new eponymous label. Three years passed between Mingus and Mitchell‘s next album Wild Things Run Fast, which was seen by some as a return to Mitchell‘s more traditional 70s songwriting, leavened with 80s synthesizers. The jazz influence still lingered, though, as did some of the players from Mitchell‘s recent records and tour, including Wayne Shorter. We‘ll hear him on one of the songs from Mitchell‘s Geffen debut, and as a participant in a 1987 TV broadcast that brought a number of other jazz luminaries together with Mitchell, including vocalist Bobby McFerrin, pianist Herbie Hancock, saxophonist David Sanborn, bassist (and Mitchell partner) Larry Klein, and drummer Vinnie Colaiuta. First, here‘s Joni Mitchell and "Moon At The Window" on Night Lights:

In the past several decades Joni Mitchell‘s songs have become a part of the modern jazz canon, performed by numerous artists including Tierney Sutton, Brad Mehldau, and Cassandra Wilson, a longtime admirer of Mitchell‘s who taught herself to sing and play guitar using Mitchell songs. When she was interviewed along with Mitchell for a 1996 Downbeat cover story she said, "I didn‘t think about jazz when I started listening to Joni. I think everything we‘ve produced in America is jazz…because we‘ve learned how to improvise." Perhaps most prominently, frequent Mitchell collaborator Herbie Hancock released a tribute in 2007 called River: The Joni Letters. But I‘ll go back to the source to close out this edition of Night Lights, with music from a 2000 Joni Mitchell album that put her vocals in a with-strings context. Most of the material was drawn from the standards repertoire of singers such as Billie Holiday, but the title track was all Joni:

Outtakes

From Ed Ward's 1979 review of Mingus:

She's not so much trying to become a jazz singer as trying to adapt her narrative/confessional style to the conventions of improvised jazz-vocal lyrics, where the placement of vowels and syllables and the creation of irregular internal rhyme-schemes are as important as, or more important than, the lyrical content itself. In other words, her model here is more Eddie Jefferson than Billie Holiday. Her framework is some tunes which were worked up by some more traditionally oriented jazz musicians (Eddie Gomez, Phil Woods, Gerry Mulligan, Dannie Richmond) under Mingus's direction, then handed over to a stone fusion band (Stanley Clarke, John McLaughlin, Jan Hammer) whose efforts were discarded, and finally interpreted by musicians who straddle the fence (Jaco Pastorius, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock). The real acid test is where she takes a Mingus chestnut, "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat," and adds her lyrics. The band passes with straight A's, she sings nicely, and the lyric, a brave try, nearly succeeds even though it's just a bit over literal.

From a 1983 interview with Vic Garbarini for Musician Magazine:

VG: After eight years of experimentation with jazz and polyrhythmic music, you've come back to rock 'n' roll What caused you to take the leap in the first place, and why come back now?

JM: Well, after Court And Spark I got fed up with four beats to the bar, and by the time I hit the Mingus project I was having the rhythm section play totally up in the air. Nobody was anchoring the music. I wanted everything floating around.

VG: Just a need to break up patterns and let go?

JM: Yeah, I was trying to become the Jackson Pollock of music (laughs). I just wanted all the notes, everybody's part, to tangle. I wanted all the desks pushed out of rows, I wanted the military abolished, anything linear had to go. Then at a certain point I began to crave that order again. So doing this album was a natural reentry into it.

VG: How would you say your approach to rock has changed as a result of your jazz and experimental work?

JM: For one thing my phrasing against the beat changed radically. A rock singer usually sings tight up with the rhythm section. The rhythm section on the new album is still expressive even while they're anchoring, so if they come in on the downbeat I don't have to sing (heavily on the beat) "DOWN TO DAH RIV-AH BAY-BY." I can come in on the end if I want to, or cluster up anywhere--jazz phrasing--and still keep the rock groove going.

Also check out this previous Night Lights program about Mitchell collaborator Jaco Pastorius.