As the 1990s brought the 20th century to a close, women musicians continued to increase their visibility in the jazz world and to erode the notion of gender distinction imposed by many male jazz critics and performers for much of the music‘s history, though the pace of change could seem inexorable at times. "There are a lot more women playing and coming into their own," drummer Terri Lyne Carrington told author Leslie Gourse in 1994. "It‘s no longer a matter of women being fashionable or a fad. It‘s really serious. When a woman says she plays, you have to listen and find out now." In the previous decade important histories of women in jazz like Linda Dahl‘s Stormy Weather and Sally Placksin‘s American Women In Jazz had been published, and Kansas City had hosted a women‘s jazz festival from 1978 to 1985.

Record companies, too, had begun to take notice of the growing number of women on the jazz scene. The storied Blue Note label, like many other jazz record labels of the mid-20th-century, had recorded very few women jazz artists in its heyday, but the company‘s late-20th-century reincarnation was a different story, carrying musicians such as singers Dianne Reeves and Cassandra Wilson, and pianists Geri Allen and Renee Rosnes on its roster. Rosnes was a Canadian who moved to New York City in the 1980s and became a pianist of choice for jazz veterans such as J.J. Johnson, Joe Henderson, and James Moody. Wilson had emerged from the experimental 1980s M-Base collective scene, and her first two albums for Blue Note helped reset the concept of modern jazz-and-popular-song repertoire, drawing on songs by artists such as Neil Young, U2, and Hank Williams. Still, she opened her 1995 album New Moon Daughter with a bold choice associated strongly with jazz icon Billie Holiday: "Strange Fruit," a haunting 1939 song written as a musical protest against lynching.

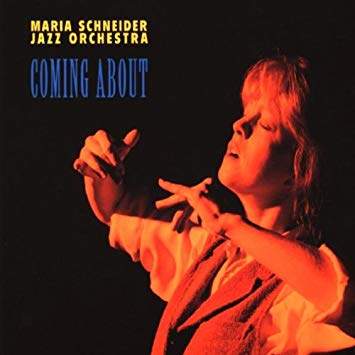

Diana Krall, like Renee Rosnes a Canadian, emerged as both a pianist and a singer in the 1990s and went on to become one of the most popular jazz-and-popular-song artists on the modern music scene, winning five Grammys in the process. Although she originally wanted to be an astronaut and excelled at science, she played jazz from her adolescence on and attended Boston‘s renowned Berklee School in the early 1980s. Like one of her influences, Nat King Cole, Krall‘s skill as a piano player has tended to be overshadowed by her success as a vocalist, and she has spoken of contending with a prejudice that claims that success stems in part from Krall‘s being marketed as a conventionally attractive woman. Another multiple-Grammy-winner, bandleader and composer Maria Schneider, was a protégé of the legendary arranger Gil Evans and began an ambitious run of recordings that continues into the present. She has become a strong advocate for musicians receiving proper compensation in the why-pay-for-it musical media landscape of the 21st century, and has also been a pioneer of what‘s come to be known as crowd-funding through her releases on the Artistshare label beginning in 2004.

In addition to these women jazz artists who rose to prominence in the 1990s, some artists returned to prominence. Singer and pianist Shirley Horn, championed by, among others, Miles Davis, had retreated from a promising jazz career in the 1960s, focusing on her family life in her hometown of Washington, D.C., although she continued to play gigs around the city. In the late 1970s and 80s she resumed active recording, and in 1987 signed with the Verve label, where she gained increasing critical and commercial attention for her elegantly spare and soulful, often-trio-based approach. As the 1980s wound down Verve also signed Abbey Lincoln, the singer who had morphed from a nightclub chanteuse into a political activist in the 1960s, and who‘d recorded infrequently ever since. Lincoln made eight albums for Verve in the 1990s that re-established her as a force to be reckoned with in the jazz world, and her independent views established her as a role model for younger women jazz artists.

Like Horn and Lincoln, singer Betty Carter had first emerged into the jazz spotlight decades earlier, joining Lionel Hampton‘s big band when she was still a teeanger, and like them she had been less visible in recent years, though she had made a number of recordings that she had released on her own Bet-Car label, making her an early adopter of the "do-it-yourself" model. Known as a fiercely independent artist and person, in 1987 Carter, like Horn and Lincoln, signed with Verve and began a late-period professional renaissance, winning a Grammy in 1988 for her album Look What I Got. Like Lincoln, Carter wrote some of her own repertoire, and we close this 1990s jazz-women edition of Night Lights with her performance of "Love Notes," a song that she composed with Mark Zubek, featuring fellow Detroit native Geri Allen on piano.