The pianist and composer first emerged from mid-20th century Argentina as a jazz artist, working with Dizzy Gillespie and recording under his own name as well.

Lalo Schifrin is best known for his Mission: Impossible theme and numerous other film and TV scores such as Bullitt, Dirty Harry, Cool Hand Luke, and Mannix. But his musical legacy runs far deeper than his considerable accomplishments in the world of scores and soundtracks, drawing deeply on both classical music and jazz-and it was jazz that put Schifrin on the musical map in the first place, as both a pianist and a creator of rich musical realms. Jazz writer Gene Lees praised Schifrin in a 1964 DownBeat article as "a composer, in the fullest European sense of the word: a man who starts with thematic material of his own and develops it into large, complex musical structures." On this edition of Night Lights we‘ll hear some of Schifrin‘s collaborations with Dizzy Gillespie and his own leader dates, as well as a bossa-nova side with trombonist Bob Brookmeyer and an excerpt from the jazz mass that Schifrin composed for Paul Horn.

Lalo Schifrin was born in Buenos Aires, Argentia on June 21, 1932. His father was a music conservatory professor and concertmaster of the Buenos Aires Philharmonic Orchestra; Schifrin‘s first piano instructor was Daniel Barenboim‘s father, who rapped Schifrin‘s fingers with a sharp pencil whenever the child made a mistake, making the lessons "both boring and terrifying," as Schifrin later recalled. He discovered jazz as a teenager and later referred to it as a "religious conversion," listening to hard-to-obtain records of Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Bix Beiderbecke, and other jazz greats. In college he fell under the spell of bebop masters such as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. In 1952 he traveled overseas to study at the Paris Conservatory, then returned to Argentina in 1956 and became the leader of a popular jazz orchestra that played on both television and radio shows. A momentous meeting was about to occur that would eventually take Schifrin out of Argentina again; but first, let‘s hear one of Schifrin‘s early recordings, a dramatic interpretation of Juan Tizol and Duke Ellington‘s "Caravan":

Pianist Lalo Schifrin‘s take on Juan Tizol and Duke Ellington‘s "Caravan," from his 1959 album Piano Espanol. By then Schifrin was in New York City, as a result of an encounter with a musical idol several years earlier. As a teenager Schifrin had joked to his mother whenever he left the house, "If Dizzy Gillespie calls, tell him I‘m not here!" So he was thrilled when Gillespie brought his big band to Buenos Aires in 1956 as part of a U.S. State Department tour. Schifrin attended all of Gillespie‘s concerts and the trumpeter in turn heard Schifrin leading his orchestra. Impressed when he learned that the music being played had all been arranged by Schifrin, Gillespie invited the young pianist to come to the United States.

It took Schifrin a year and a half to meet the requirements to immigrate, but he did eventually make it to New York City. Gillespie already had a pianist, but he asked Schifrin to write something for him. The resulting extended suite, Gillespieana, became one of Gillespie‘s most renowned recordings, and Schifrin took over the piano chair in the trumpeter‘s band at the beginning of the 1960s. Gillespie‘s biographer Alyn Shipton compared Schifrin‘s partnership with Gillespie to that of Miles Davis and arranger Gil Evans, praising Schifrin‘s "original orchestral palette and melodic imagination." We‘ll hear music from two large-ensemble albums that Gillespie recorded with Schifrin, both featuring the composer on piano, beginning with "Panamericana" from Gillespieana:

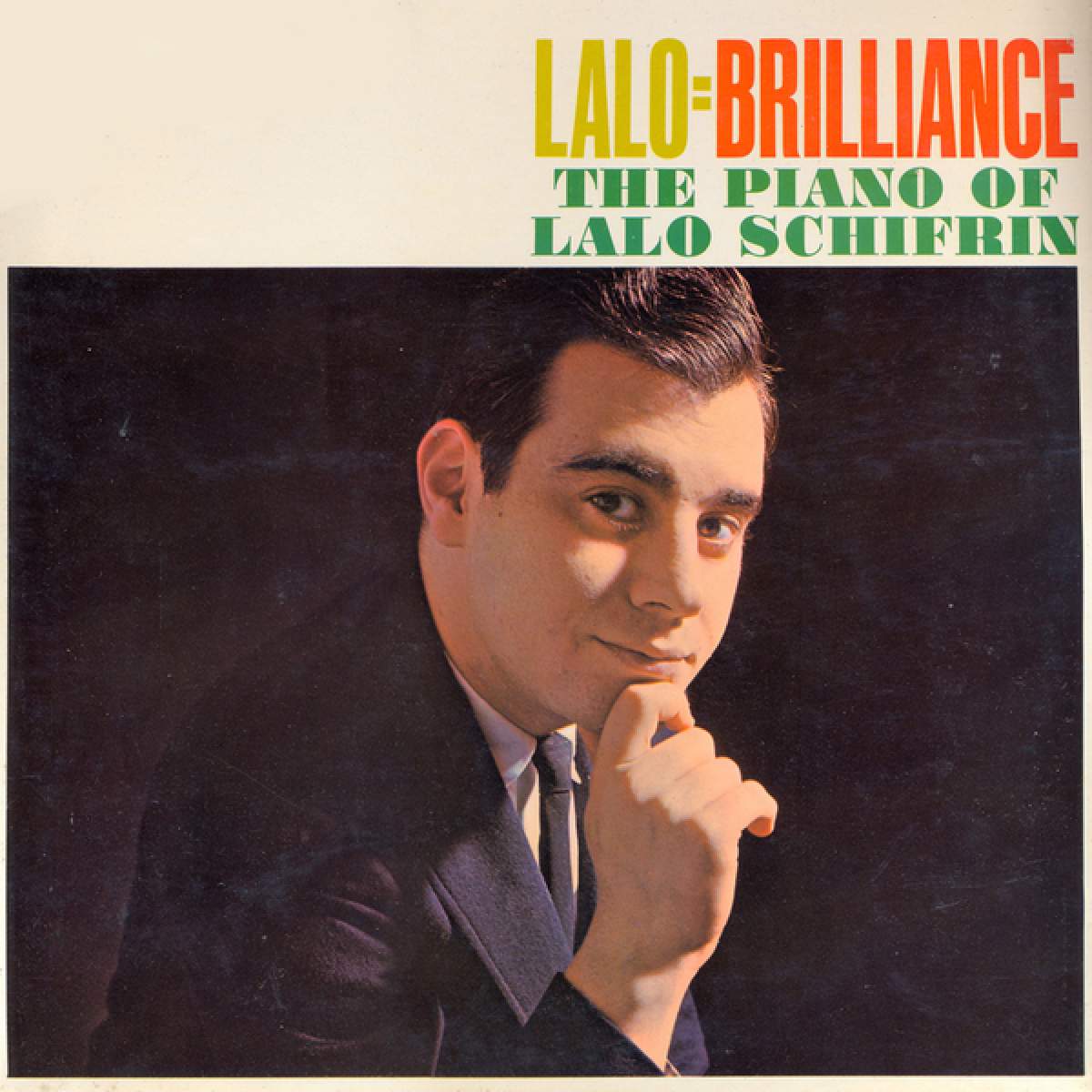

Schifrin‘s work with Gillespie served as a launching pad for further albums under his own name that showcased his broad interpretive and arranging gifts. One album, Piano, Strings, And Bossa Nova, was prepared and recorded in rather unnerving circumstances, Schifrin later recalled, just as the Cuban Missile Crisis was ending. Another, Lalo = Brilliance, drew on musicians Schifrin had worked with in Gillespie‘s band. DownBeat‘s review of Lalo = Briliance called Schifrin "a man of perhaps too many talents," but praised him for his "skill in dealing with uncommon time signatures and his ability to write big for small groups. Here‘s Lalo Schifrin with his arrangement of Dizzy Gillespie‘s "Kush":

In addition to Dizzy Gillespie, in the early 1960s Schifrin also worked and recorded with saxophonists Stan Getz and Johnny Hodges, vibraphonist Cal Tjader, and singers Sarah Vaughan and Pat Thomas. His career was taking off, and he left Gillespie‘s band at the end of 1962, though he would speak warmly of the man he considered to be his jazz mentor for decades to come. In one of his first post-Gillespie projects, Schifrin collaborated with trombonist Bob Brookmeyer, who like many other jazz artists was attempting to ride the bossa-nova wave of the early 1960s. The title track of their album Samba Para Dos, written by Schifrin, was singled out by DownBeat‘s reviewer for Schifrin‘s piano solo, described as "a lashing, urgent, continually arresting improvisation that is spellbinding in its force and power. Angular and brooding, it builds relentlessly and never once lets up."

The following year Schifrin made New Fantasy, an album that he later cited with pride in his memoir Mission Impossible: My Life In Music. Employing an all-star jazz lineup, Schifrin recorded his arrangements of a diverse set of composers ranging from Aaron Copland and George Gershwin to Heitor Villa-Lobos and Richard Rodgers, once again demonstrating the wide array of musical backgrounds that he drew on to compose his own music:

At the end of 1964 Schifrin collaborated with jazz artist Paul Horn on an unusual project, writing and recording a jazz mass. The concept of sacred jazz was taking hold in the increasingly liberalized world of the 1960s, and the Second Vatican Council had recently decided to let masses be sung in a country‘s native language rather than only in Latin. Schifrin, whose mother was Catholic, wrote in his memoir that "the idea of a dialogue between Gregorian chant and a jazz ensemble was very appealing." The recording session started at midnight: "the studio was dimly lit," Schifrin wrote, "and the experience was truly spiritual." Horn and Schifrin did an interview with DownBeat when the album came out in which Schifrin stated, "Jazz is the music of our time. I think it makes sense to introduce the vitality of jazz into this form." From Jazz Suite On The Mass Texts, here‘s "Sanctus":

Jazz Suite On The Mass Texts won two Grammys after it was released in 1965. The following year Lalo Schifrin wrote a theme for a new spy-thriller TV program called Mission: Impossible, and his already-busy career as a film and television composer gained even more momentum; in the next few years he would go on to write music for the movies Bullitt and Dirty Harry, the theme for the TV-crime show Mannix, and many others. But Schifrin kept his hand in the jazz game, recording a series of "Jazz Meets The Symphony" albums in addition to his numerous other classical and film-score recordings. In 1997 he wrote "Rhapsody For Bix", an extended work commissioned by the Bix Beiderbecke Jazz Memorial Society in honor of the legendary musician who was one of the first jazz artists the adolescent Schifrin ever heard on record. In his memoir Schifrin wrote that he wanted to interweave Beiderbecke‘s music, the trumpeter‘s love for classical composers such as DeBussy, his experiences growing up on the Mississippi River and participating in the speakeasy culture of early 1920s Chicago, and Schifrin‘s own themes into one work.

Celebrating Beiderbecke‘s legacy on such a broad musical canvas was a fitting tribute as well to Schifrin‘s own artistic path-one that took him from his rich musical roots in Argentina to New York City, Hollywood, and around the world. I‘ll close with music recorded by Lalo Schifrin the same year that Mission: Impossible made its TV debut. The album‘s concept, combining varieties of European music with jazz, came from producer Creed Taylor; its title, one of the oddest in the entire discography of jazz, was inspired by Schifrin‘s having seen the hit Broadway musical Marat/Sade. From the 1966 album The Dissection and Reconstruction of Music From The Past as Performed by the Inmates of Lalo Schifrin‘s Demented Ensemble as a Tribute to the Memory of the Marquis de Sade, here's Lalo Schifrin and "Old Laces":

Outtakes

Read an article about Schifrin's Gillespieana suite.