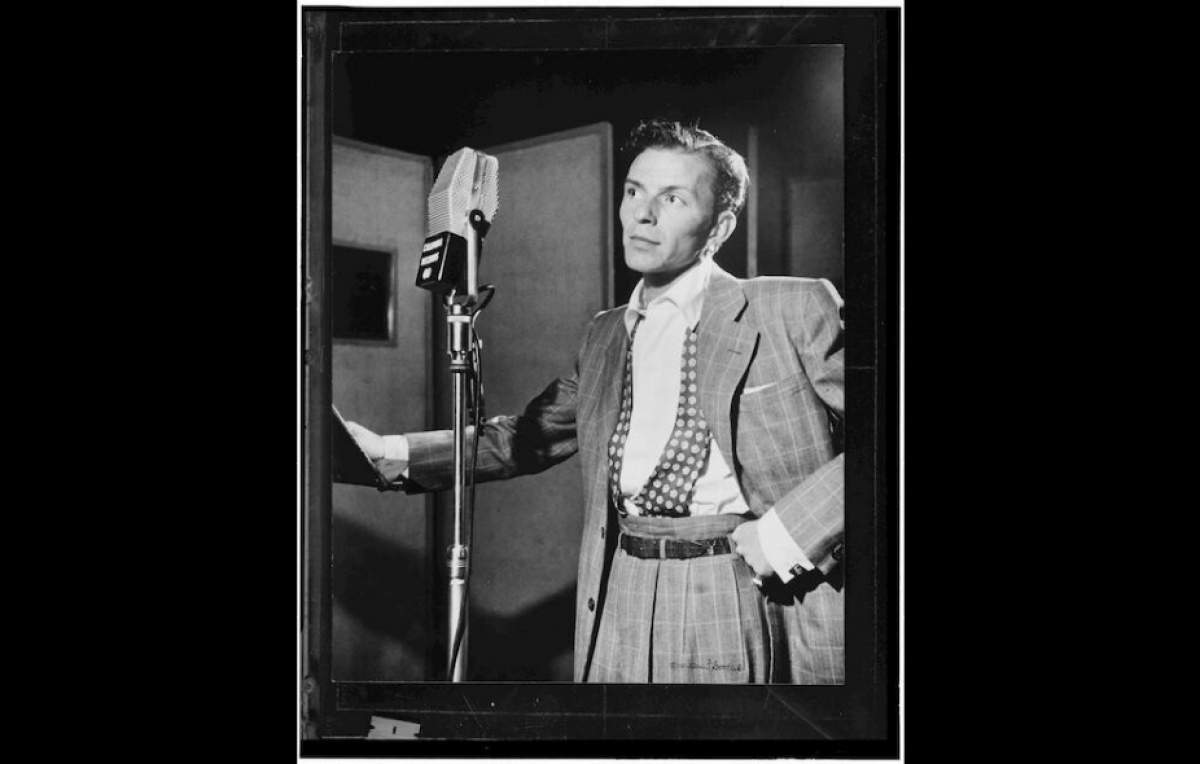

Frank Sinatra cut a wide and complicated figure across 20th-century American popular culture, swaggering and vulnerable, on top of the world and down on his luck, a teenybopper idol and a movie star adored by millions who often sang of loneliness, a child from an up-by-their-bootstraps immigrant family who seemed to fulfill the American dream and knew its dark side all too well. You can say unequivocally that he was a great singer, but even then some have argued for decades over whether or not to define him as a "jazz singer." On this edition of Night Lights we'll hear Sinatra in a number of jazz contexts with Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, Coleman Hawkins, Louis Armstrong, Red Norvo, Count Basie, Antonio Carlos Jobim, and Ella Fitzgerald.

A Child Of The Jazz Age

In 1956 the great tenor saxophonist Lester Young told jazz writer Nat Hentoff, "If I could put together exactly the kind of band I wanted, Frank Sinatra would be the singer." That remark alone should be enough to give Sinatra jazz credibility, though any even brief trip through his massive discography will instantly give further evidence through his inimitable phrasing, his legendary long lines that left other vocalists breathless with wonder, the intensity of feeling in his delivery of lyrics, and an innate sense of swing. It's no wonder that he also counted Miles Davis and Billie Holiday among his admirers.

Sinatra grew up as an only child in an Italian-American family during the era of Prohibition, big band music, and the explosion of radio, movies, and phonograph records. He was a child of the Jazz Age who first made his mark singing with the orchestra of trumpeter Harry James, then rocketing to stardom as the front man for Tommy Dorsey's outfit, before becoming one of the first vocalists to launch a solo career. He would rise, fall, and then rise again, a centrifugal force in mid-20th century American show business. Why was he so significant?

Maybe it's because nobody could inhabit a song like Sinatra. Talk show host Bill Boggs, who as a teenager saw Sinatra in 1960, said the singer made the songs he sang seem like "a preview of adult life." Writer and Sinatra friend Pete Hamill said that the singer "created an urban American voice" whose artistic subject was "loneliness." We'll to hear that voice in some of its most jazz-saturated settings on this edition of Night Lights, making the case that Sinatra was indeed a jazz singer. We'll start off with two recently-released 1946 broadcasts from the "Songs By Sinatra" radio show that feature the singer with two fellow stars of the jazz world-pianist Nat King Cole's trio, and clarinetist Benny Goodman's sextet:

The above was not Sinatra's only encounter with Nat King Cole. In December of 1946 the singer and pianist found themselves in the company of saxophonists Coleman Hawkins and Johnny Hodges, as well as two fellow alumni from the Tommy Dorsey band, trumpeter Charlie Shavers and drummer Buddy Rich, and other top-notch jazz musicians for an all-star recording date sponsored by Metronome Magazine. Sinatra sounds right at home in this company on a lightly swinging rendition of "Sweet Lorraine." We'll also hear another radio recording, made in the mid-1950s for Sinatra's program To Be Perfectly Frank, which consistently featured him in a small-group jazz setting, with a Latin-jazz, flute-and-bongo-fueled rendition of a song Sinatra did numerous times throughout his career-Cole Porter's "Night And Day":

Sinatra crossed musical paths on a number of occasions with other jazz giants of the mid-20th-century, including Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald. Sinatra and Armstrong teamed up with Bing Crosby for the 1956 film High Society, and Armstrong, Sinatra, and Fitzgerald were all involved with the soundtrack for an animated film adaptation that never came to pass, based on the musical Finian's Rainbow, shelved after the film's director, John Hubley, and songwriter Yip Harburg refused to testify before the House on Un-American Activities Committee. We'll hear a duet from the abandoned soundtrack performed by Sinatra and Fitzgerald, preceded by this, a 1945 Jubilee broadcast that paired Sinatra and Armstrong for "Blue Skies":

Arrangers And Bandleaders

In the early 1950s Sinatra began to emerge from the slump he'd hit at the end of the 1940s, winning an Academy Award for his role in From Here To Eternity and signing with Capitol Records, where he would make many of the albums that listeners and critics today generally consider to be his masterpieces. An instrumental force behind those records was provided by arranger Nelson Riddle, who came on board not long after Sinatra began recording for Capitol. Riddle, as Sinatra biographer James Kaplan has noted, "brought along not only his deep grounding in the complex orchestral textures of the French impressionist composers, but also his big-band chops."

A highly empathetic arranger when it came to working with vocalists, Riddle was able to conjure tonally rich, dynamic charts for both Sinatra's ballads and his swingers. We'll hear a low-key rendition of Cole Porter's "What Is This Thing Called Love," from In The Wee Small Hours, the album that might well embody Riddle's quote that "Ava Gardner taught him how to sing a torch song… Ava taught him the hard way." First, this, considered to be one of Sinatra's greatest recordings, also of a Cole Porter song. Riddle was a fan of the classical composer Maurice Ravel and said that his arrangement of Cole Porter's "I've Got You Under My Skin" was inspired by Ravel's "Bolero." Listen to the dramatic way he and Sinatra build and release musical tension in this epic performance:

Though Riddle was Sinatra's most prominent and significant collaborator during his amazing run of albums from the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s, Sinatra also enlisted other arrangers and bandleaders who helped spark some of his most notable jazz moments. In this next set we'll hear the singer live in Australia with a small group helmed by vibraphonist Red Norvo, who had his own roots in the swing era, as well as a studio recording with arranger Billy May that became a classic example of big-band Sinatra on a manic upswing, powered by the glide and brassy punch of May's chart for"Come Fly With Me":

In the early 1960s Sinatra left Capitol Records and began his own label, Reprise, signing friends such as Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr. to it. Sinatra signed some jazz veterans as well, including Count Basie, whom Sinatra had long admired and wanted to work with. The two teamed up for two albums on Reprise, the first arranged by Basie chartsmith Neal Hefti, the second by a young Quincy Jones. Nearly thirty years on from their respective debuts in late-1930s New York City, Basie and Sinatra produced musical gold. Here they are doing "Pennies From Heaven":

We close out this edition of Night Lights with two late-1960s recordings that brought Sinatra together with Antonio Carlos Jobim, a recently-risen star whose compositions were expanding the geographical boundaries of the Great American Songbook, as well as another veteran big-band leader with whom Sinatra had long wanted to work: Duke Ellington. By this time Sinatra, like so many other singers and musicians whose roots were in the swing and bop eras, was finding it more and more difficult to adapt to changing trends in popular music, even though he still had two big hits to come in "My Way" and "New York, New York." His bossa-nova jazz collaborations with Jobim provided one graceful instance of a newer style that fit Sinatra well, while his studio encounter with Ellington's band, orchestrated by Billy May, put him back into the big-band context in which his career had begun:

Sinatra By The Book

- Will Friedwald, Sinatra! The Song Is You: A Singer's Art

- Pete Hamill, Why Sinatra Matters

- James Kaplan, Frank: The Voice

- James Kaplan, Sinatra: The Chairman

- James Kaplan, "Frank Sinatra's 'I've Got You Under My Skin': The Full Story (excerpt from SINATRA: THE CHAIRMAN)