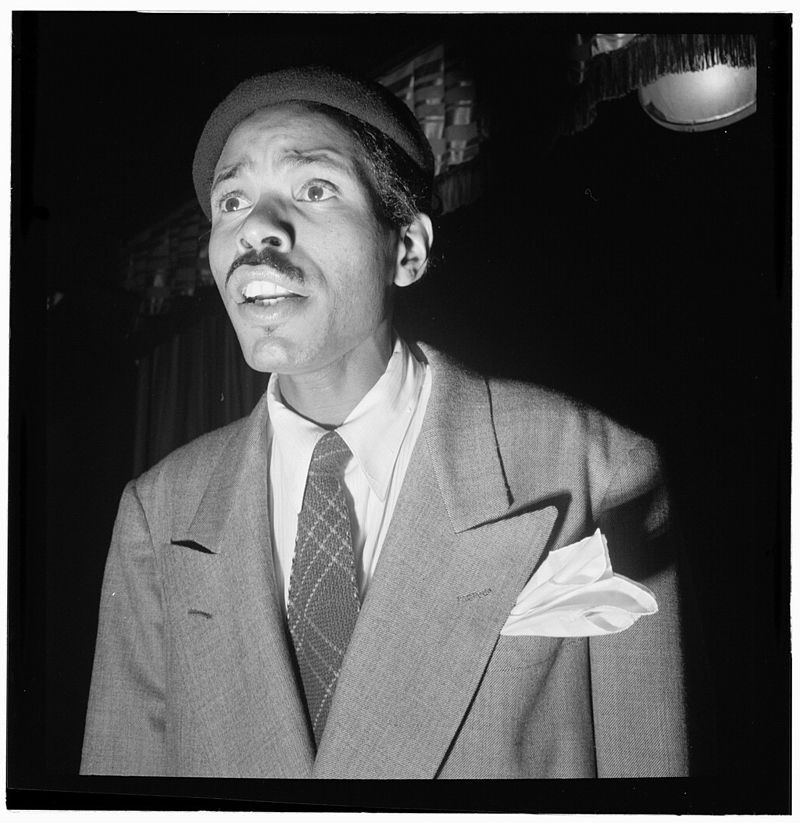

Welcome to Night Lights… I’m David Brent Johnson. Babs Gonzales was the toastmaster of the bebop scene, a vocalese hipster who made the scene and lived to sing and write about it. His bop-fueled streetwise parables grew out of an innovative lifestyle and a deep-seated love of jazz.

In the next hour we’ll hear his and Tadd Dameron’s original version of a song that became a hit for Dizzy Gillespie, a recording that served as a studio debut for the young saxophonist Sonny Rollins, live performances from Small’s Paradise in Harlem, and more. It’s “How Professor Bop Paid His Dues: Babs Gonzales”… coming up on this edition of Night Lights.

Music/newshole:

Babs Gonzales, “Get Out Of That Bed” (2:18)

Babs Gonzales, “Manhattan Fable” (2:38)

Babs Gonzales with “Manhattan Fable” and before that, “Get Out Of That Bed”.

Segment 3: music bed—BG, “Real Crazy”

“The people who make jazz, be they mean, moody, or magnanimous, are often as flamboyant and outlandish as the music itself.” That’s how Valerie Wilmer opened her 1977 profile of the singer, hustler, and master of bebop ceremonies Babs Gonzales. “On the other hand,” Wilmer continued, “there are the jazz people whose influence at best can be described as minor, yet who are well known to musicians and listeners alike… you’d have to be hard-pressed to ignore the wealth of legend that surrounds the singer and humorist, Babs Gonzales, who is said to have once caused a minor furor on the Champs Elysees by appearing in an orange, brown, and purple check coat of excessive length, a black shirt and chrome yellow bow-tie, with a grey and red-check beret topping the whole confection like the cherry on a trifle.”

Trust Babs Gonzales to always leave them looking, listening, laughing, and remembering.

Troubadour of hipster parables, streetwise entertainer, hustler on the make, author, and all-around jazz personality, he was born as Lee Brown on October 27, 1919 in Newark, New Jersey. Early in life he found lucrative pastimes on the street and in the world of the big bands, working as a band boy for Jimmy Lunceford, and later as a singer for Lionel Hampton and Charlie Barnet. He moved to Los Angeles in the early 1940s and undertook the first of a number of racially subversive acts, wearing a turban and calling himself “Ram Singh” in order to make himself more employable, later changing his last name to Gonzales in order to pass as a Latino American. He landed a gig as chauffeur for the movie star Errol Flynn. These were the World War II years, and eventually Gonzales went home to Newark to report for military duty; in his memoir I PAID MY DUES: GOOD TIMES… NO BREAD, he details the cross-dressing antics he engaged in in order to be classified as unfit for service. He also fell in with the newly-emerged bebop scene, and collaborated with one of its brightest young talents, arranger, composer, and pianist Tadd Dameron, in a group known as Three Bips and a Bop. From their first 1947 recording session for Blue Note Records, here’s Gonzales’ composition “Oop-Pop-A-Da,” on Night Lights:

Babs Gonzales/Three Bips And A Bop, “Ooo-Pop-A-Da” (2:50)

Babs Gonzales/Three Bips And A Bop, “Weird Lullaby” (2:57) (total time: 5:47)

Three Bips and a Bop in 1947 performing Babs Gonzales’s songs “Weird Lullaby” and before that “Oop-Pop-A-Da ,” with Gonzales on vocals, Tadd Dameron on piano, Rudy Williams on alto sax, Pee Wee Tinney on guitar, Art Phipps on bass, and Charles Simon on drums. “Oop-Pop-A-Da” got only limited regional exposure, until trumpeter and bandleader Dizzy Gillespie recorded his own hit version for the Victor label later that year. Babs had to push Dizzy and Victor to get proper accreditation and royalties, but his career was off and running, with bebop and Babs’ own brand of bop vocalese in vogue. Though Tadd Dameron departed to pursue different musical projects, Gonzales stayed on track with recordings like this one, made for the Apollo label in 1947—“Everything Is Cool,” on Night Lights:

Babs Gonzales, “Everything Is Cool” (2:50)

Babs Gonzales performing “Everything Is Cool,” recorded for the Apollo label in 1947.

From the start, Gonzales was often able to corral exceptional jazz talent for his forays into the studio. “He always comes around hustling with his tunes,” pianist Wynton Kelly once noted. “Seems like he heard about the recording session even before we did!” In 1949 he provided an 18-year-old Harlem saxophonist named Sonny Rollins with his first professional recording opportunity, and trombonist J.J. Johnson was along for the ride as well. “Professor Bop” described a character that came off as a cross between Dizzy Gillespie and Babs himself, steeped in Gonzales’ bop-scat vocabulary. Babs Gonzales and “Professor Bop,” on Night Lights:

Babs Gonzales, “Professor Bop” (2:25)

Babs Gonzales, “St.Louis Blues” (2:36) (total time: 5:01)

Babs Gonzales’ version of W.C. Handy’s classic “St. Louis Blues,” with a lineup that included young and up-and-coming jazz musicians such as trombonist J.J. Johnson, tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins, pianist Wynton Kelly, and drummer Roy Haynes, recorded in 1949. Gonzales before that with his own tune “Professor Bop,” also recorded in 1949, and again with J.J. Johnson and Sonny Rollins present—it was the very first recording session for Rollins, only 18 years old at the time.

In the early 1950s Gonzales spent the first of several sojourns in Europe and ended up connecting with James Moody, serving as the saxophonist’s musical director and occasional vocalist for a two-year spell. In 1953 Moody’s orchestra recorded a number penned by Gonzales in tribute to the leader, and featuring Babs on vocals as well… here’s “The James Moody Story,” on Night Lights:

Babs Gonzales w/James Moody, “The James Moody Story” (2:22)

Babs Gonzales with saxophonist James Moody and his orchestra performing “The James Moody Story,” recorded in 1953. I’ll have more of the performances of Babs Gonzales in just a few moments. You can listen to many previous Night Lights programs on our website at wfiu.org/nightlights. Production support for Night Lights comes from Columbus Visitor's Center, celebrating EVERYWHERE ART AND UNEXPECTED ARCHITECTURE in Columbus, Indiana. Modern architecture and design to explore forty-five minutes south of Indianapolis. More at Columbus dot I-N dot U-S. I’m David Brent Johnson, and you’re listening to “How Professor Bop Paid His Dues: Babs Gonzales,” on Night Lights.

Bennie Green, “Soul Stirrin’” or Babs Gonzales, “Le Continental”? “Movin’ and Groovin”? (1:00)

I’m featuring the music of Babs Gonzales on this edition of Night Lights. Gonzales was a ubiquitous figure on the mid-20th century jazz scene in New York City and beyond, hustling, writing, recording, performing, making money, spending money, losing money, and putting all of it into his unique art. “To spend a half hour in conversation with Gonzales is to live temporarily in another world,” Valerie Wilmer wrote of him. “The world of the night people, the gamblers, the showmen, the sportsmen, the whores and the pimps, the world that is alternately flamboyant and seedy.” He was a walking dictionary of hip slang and a keen observer of human nature, and his 1967 autobiography I PAID MY DUES: GOOD TIMES… NO BREAD can easily take its place beside other jazz subculture memoirs such as Charles Mingus’ BENEATH THE UNDERDOG and Mezz Mezzrow’s REALLY THE BLUES. His influence was limited, though to hear Oscar Brown Jr.’s early 1960s song “40 Acres and a Mule,” for instance, is to feel certain that he was hip to the sides that Gonzales had been laying down over the years. Gonzales led a highly individual and free-spirited life in an age where African-Americans chafed and died under the weight of segregation and violent racism, which undoubtedly contributed to the harder edges of his commentary. Somehow he always managed to make his subject matter entertaining.

Here’s Babs’ Yuletide offering about the most wonderful time of the year in his part of town: “The Bebop Santa Claus,” on Night Lights:

Babs Gonzales, “The Be-Bop Santa Claus” (3:20)

Babs Gonzales with a bop twist to his season’s greetings, “The Bebop Santa Claus,” recorded in 1955. Gonzales’ path continued to intersect with established and up-and-coming jazz artists throughout the 1950s. He was an early champion of Jimmy Smith and wrote the liner notes for one of the organist’s first Blue Note LPs. He recorded with Smith as well, dispensing yet another lesson from the school of Babs—“You Need Connections,” on Night Lights:

Jimmy Smith/Babs Gonzales, “You Need Connections” (3:00)

Babs Gonzales performing his song “You Need Connections,” backed by Jimmy Smith on organ, Thornel Schwartz on guitar, and Donald Bailey on drums, recorded for Blue Note Records in 1956. Two years later Gonzales made his first full-fledged LP, called VOILA, that found him in fine jazz company with Melba Liston overseeing arrangements and saxophonists Johnny Griffin and Charlie Rouse, pianist Horace Parlan, drummer Roy Haynes, and flutist Les Spann. Here’s Gonzales’ ode to the jazz life, “Movin’ And Groovin’,” on Night Lights:

BG, “Movin’ And Groovin’” (3:18)

Babs Gonzales singing his song “Movin’ And Groovin’” from his first album VOILA, recorded in 1958. Though Gonzales could certainly hold his own among top-notch jazz musicians, jazz critic Nat Hentoff cast him in another lineage for his liner notes to Gonzales’ 1959 followup, TALES OF MANHATTAN. “To my mind,” Hentoff wrote, “Babs is most creative and most valuable as a commentator on contemporary urban snares and delusions… he is somewhat in the same vein as Langston Hughes’ Simple or Bootsie in Ollie Harrington’s cartoons in the Pittsburgh Courier. Babs spends a lot of his time observing the hall of funhouse mirrors that passes for many people’s lives in the big cities… he touches something in the lives of nearly all of us.” Babs Gonzales painting a portrait of New York City pivoting from the late night to the early morning hours with “Broadway 4 A.M.,” on Night Lights:

Babs Gonzales, “Broadway 4 A.M.” (2:48)

Babs Gonzales, “A Dollar Is Your Only Friend” (2:56) (total time: 5:44)

Babs Gonzales with “A Dollar Is Your Only Friend” and “Broadway 4 A.M.” before that, from the 1959 album TALES OF MANHATTAN, with arrangements by Melba Liston, and musicians that included guitarist Kenny Burrell and drummer Roy Haynes. For all of his hipster proselytizing, Gonzales could preach to social issues of the day as well. His memoir I PAID MY DUES: GOOD TIMES.. NO BREAD is rife with accounts of the racism that he and other African-Americans routinely faced in mid-20th-century America. Although Gonzales relates these reoccurring and maddening incidents with resilient verve and frequent outcomes in which he outfoxes or maneuvers his way around the racial barriers, the bitter disparity of such conditions in a country that promoted itself around the world as a beacon of freedom was portrayed vividly in a song that Gonzales wrote as the civil-rights movement was in the ascent in the early 1960s. Here’s a live performance at Harlem’s Small’s Paradise in 1962 of “We Ain’t Got Integration,” on Night Lights:

Babs Gonzales, “Integration” (3:10)

Babs Gonzales performing his song “We Ain’t Got Integration” at Small’s Paradise in Harlem in 1962, with Johnny Griffin on tenor sax, Clark Terry on trumpet, Horace Parlan on piano, Buddy Catlett on bass, and Ben Riley on drums. Even though Gonzales came to be seen as a man left behind by the times—Valerie Wilmer’s sympathetic portrait in her 1977 book JAZZ PEOPLE portrays him as a wily survivor from the bebop age—he was also ahead of his times in some respects. He put out his own records and published his own books, adept at self-promotion long before the emergence of social media. His story-telling and observations were bebop’s prototype for rap. He fulfilled his creed of “expubidence,” his term for originality and soul, and rode the ups and downs of a hustler’s life with pizzazz, making records along the way that constitute a subgenre of mid-20th century bop. Near the end of his 1967 memoir I PAID MY DUES: GOOD TIMES… NO BREAD” he proclaimed himself to be “rich in the art of living.” Gonzales would continue practicing that art for another 13 years, passing away in 1980 at the age of 60, leaving behind an only-sporadically celebrated legacy as one of the most colorful characters of the 20th-century jazz scene. Decades later, when editor Geoffrey O’Brien included an excerpt of Gonzales’ writing in the Library of America COOL SCHOOL anthology, he called Babs” “one of the outsider voices ignored or suppressed by the mainstream [that] would merge and recombine in unpredictable ways, and change American culture forever." I’ll close with Babs Gonzales live at Small’s Paradise in Harlem doing “Them Jive New Yorkers” and his own lyrics-added version of Thelonious Monk’s “Round Midnight” on Night Lights:

“Them Jive New Yorkers” (live version) (3:48)

“Round About Midnight” (6:22) (total time: 10:10)

I closed with Babs Gonzales performing “Round Midnight” and “Them Jive New Yorkers” from the 1962 recording SUNDAY AFTERNOON WITH BABS GONZALES AT SMALL’S PARADISE, with Johnny Griffin on tenor sax, Clark Terry on trumpet, Horace Parlan on piano, Buddy Catlett on bass, and Ben Riley on drums. Thanks for tuning into this edition of Night Lights. You can hear many previous Night Lights programs on our website at wfiu.org/nightlights. Production support for Night Lights comes from Columbus Visitor's Center, celebrating EVERYWHERE ART AND UNEXPECTED ARCHITECTURE in Columbus, Indiana. Modern architecture and design to explore forty-five minutes south of Indianapolis. More at Columbus dot I-N dot U-S. Night Lights is a production of WFIU and part of the educational mission of Indiana University. I’m David Brent Johnson, wishing you good listening for the week ahead.