In the late 1960s, young musicians such as The Free Spirits, the Fourth Way, and other now-forgotten fusioneers made the first attempts to blend jazz with rock.

In 1970 trumpeter Miles Davis released Bitches Brew, a landmark album that melded jazz, rock, and other elements into a sound that came to be known as "fusion." But even before Bitches Brew, fusion was beginning to churn, with young jazz musicians such as Gary Burton, Larry Coryell, and Steve Marcus incorporating the influence of rock music into the recordings they were making. We'll hear those artists and others in the next hour as we explore the fusion pioneers of the late 1960s on "First Fusion: Jazz-Rock Before Bitches Brew."

"Jazz As We Know It Is Dead!"

In June of 1967, the same month that the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, DownBeat Magazine published "A Message To Our Readers." "Rock and roll has come of age," the flagship journal of the jazz world proclaimed. "Without reducing its coverage of jazz, DownBeat will expand its editorial perspective to include musically valid aspects of the rock scene." Rock was on the rise, and jazz was on the run. That same year two legendary New York City jazz clubs, the Five Spot and Eddie Condon's, both closed, and a DownBeat cover headline stated, "Jazz As We Know It Is Dead!". Long considered to be the hip music of the counterculture, jazz now seemed either bop-stagnant or avant-garde-abrasive to young listeners who flocked to rock instead. In his book Jazz Rock, Stuart Nicholson chronicles the economic migrations and upheavals caused by jazz's declining popularity, and the growing calls of some jazz writers and mainstream media music critics for jazz to somehow find a way to align itself with rock music.

Some young jazz musicians were feeling much the same way. Older, established jazz artists generally loathed the Beatles and the rock groups that proved successful in their wake, because those groups' popularity helped crush the market for jazz, and because rock was an alien and seemingly crude music to many jazz musicians. But jazz groups with younger players led by saxophonists Charles Lloyd and John Handy were finding favor with youthful audiences, in part because of their colorful attire and vibrant music that alluded to the emerging psychedelic sound of rock.

"If John Coltrane Met George Harrison"

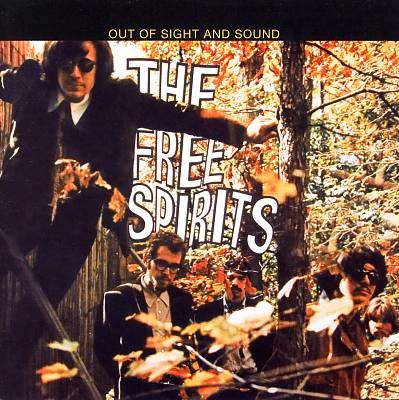

One of the first jazz-rock groups to emerge in the mid-1960s was the Free Spirits, which grew out of a music collective that jammed at a New York City club called L'Intrigue. Young musicians such as guitarist Larry Coryell, saxophonist Jim Pepper, trumpeter Randy Brecker, and drummer Bob Moses all partook of a kinetic and experimental culture that had room for both Wes Montgomery and the Rolling Stones; looking back decades later, Coryell, who had come to New York City from Seattle in 1965 at the age of 22, said the Free Spirits' sound was a result of "trying to imagine what it would be like if John Coltrane met George Harrison."

The Free Spirits opened for Jimi Hendrix, the Doors and the Velvet Underground, and recorded their debut album in late 1966 for ABC, with a repertoire written primarily by Coryell and fellow guitarist Chip Baker. Despite laudatory liner notes from jazz critic Nat Hentoff and an ABC ad touting the Free Spirits as "the ‘now' group with the ‘now' sound," Out Of Sight And Out Of Sound failed to make any kind of impact with either jazz or rock audiences, and the band themselves were dissatisfied with the record, feeling that it did not capture the expansive energy found in their live sets.

Listen to the Free Spirits performing a live, extended version of "I'm Gonna Be Free" in February 1967:

Not long after the release of Out Of Sight And Out Of Sound, Larry Coryell and Bob Moses left the Free Spirits to join Gary Burton's new quartet. Burton, who'd just quit Stan Getz's group, was a young but already experienced 24-year-old jazz artist who had forged an innovative, four mallet technique for playing vibes and was looking to create a new sound that would somehow incorporate the music that he loved in addition to jazz; on his previous two LPs he'd included songs by the Beatles and Bob Dylan. "I'm young, and I like being young," he said in the liner notes to the quartet's 1967 album Duster:

I feel like having long hair, I enjoy rock music, and feel it has an extremely important role in the future of music. It's alive and timely. But I'm not trying to ‘prove' anything with my music or the group. I am only concerned that we play what we are.

Though the Burton Quartet's recordings don't sound provocative today, some more traditionally-inclined jazz audiences didn't know what to make of Coryell's occasionally distorted guitar or the group's often freeform approach, propelled by Burton's dynamic vibes playing and the near-telepathic rapport of his bandmates.

Burton's quartet would continue to the end of the decade, with some personnel changes that included Jerry Hahn replacing Coryell on guitar. Hahn had been a member of saxophonist John Handy's unusually configured quintet that had developed a strong following with young rock audiences on the West Coast. In 1968 two key members of that quintet, pianist Michael Nock and violinist Michael White, left Handy to start the Fourth Way, named after George Gurdjieff's philosophy for awakening consciousness. Jazz fusion historian Kevin Fellezs describes Fourth Way's sound as a "protoworld fusion blend of jazz, Asian and African traditions, rock and funk, and acoustinc and electronic instrumentation that suggested the far-reaching possibilities of fusion":

The heady days of the late 1960s proved to be fertile ground for "fusioneers" who were attempting to merge their love of modern-day rock with jazz. Saxophonist Jim Sangrey has noted that

"the 'psychedelic era' was the beginning of the incorporation of real improvisation into post-Swing popular music. So opportunities for "common ground" (or possible pursuit of possibly discoverable areas of common ground) suddenly existed where none had really been before.

Groups like Cream and the Grateful Dead often incorporated long, improvisatory jams into their song structures. There was another convergence of jazz and rock as well in the sound of groups such as Blood, Sweat and Tears and Chicago, which came to be known as "big-band rock," often blending brass riffs with rock rhythms:

The first edition of Blood, Sweat and Tears included pianist Al Kooper and trumpeter Randy Brecker, who would go on to fame with brother Michael in the 1970s; and the group's second album would spawn a huge hit, "Spinning Wheel," that featured a solo by trumpeter Lew Soloff. (Columbia's ad for the second album was headlined, "Pretend It's Jazz.") These groups in turn had been influenced by the sound of trumpeter Don Ellis' big band, which used a variety of odd time signatures and blended a variety of musical influences into a brew of proto-fusion jazz:

State Of Emergency

Another fusioneer, saxophonist Steve Marcus, had a big-band heritage, having played with both Woody Herman and Stan Kenton, and he was also a part of the New York City scene that had spawned the Free Spirits. In the late 1960s he put together an ensemble that in retrospect is a sort of supergroup of early jazz-rock, Count's Rock Band, including former Free Spirits Larry Coryell on guitar, Chris Hills on bass, and Bob Moses on drums, as well as John Handy and Fourth Way pianist Mike Nock on keyboards; Gary Burton even shows up on tambourine as well. The group's sound has been described as the meeting of free jazz and acid rock. Mike Nock said, "Our idea was to play contemporary jazz over rock grooves," and on songs like the Byrds' "Eight Miles High" and the Beatles' "Tomorrow Never Knows" the group succeeded in creating a dramatic early form of fusion:

There are other musicians from the mid-to-late 1960s who delved into the realm of jazz-rock, such as vibraphonists Dave Pike and Mike Mainieri, pianist Warren Bernhardt, and flutist Jeremy Steig. But the musician who made the biggest noise, so to speak, before the fusion salvo of Miles Davis' Bitches Brew in 1970, was Davis' young drummer, Tony Williams. Davis had already begun to make the musical moves that would ultimately lead to Bitches Brew, but in the meantime Williams had formed what some call the first "power trio," Lifetime, with jazz organist Larry Young and British guitarist John McLaughlin. "My idea was to create my own audience where I didn't have to compete with any musician's concept, not let rock, not let jazz or any other form dictate my musical development," Williams said.

All three members of the group had jammed with Jimi Hendrix, and their loud, guitar-and-organ-drenched sound, powered by Williams' intense drumming that continues to draw heavily on his own jazz rhythms as well as rock rhythms, reflected the cultural, political, and musical intensity of the times. Williams said that he called their debut album Emergency! because "it was an emergency for me to leave Miles and put that band together." In 1969 jazz itself seemed to be in a state of emergency; some of the featured acts at the Newport Jazz Festival included Jethro Tull, Sly and the Family Stone, and Led Zeppelin. Miles Davis was turning his ear more and more to these sounds, and in the next few years he, Weather Report, Return To Forever, and the Mahavishnu Orchestra led by Lifetime's guitarist John McLaughlin would take jazz, artistically and commercially, through perhaps its last great sea change. The age of fusion was about to dawn.

Further First Fusion

- Listen to a previous Night Lights program about the mid-1960s group of Charles Lloyd

- Read a Night Lights interview with saxophonist John Handy about the mid-1960s music scene

- Check out the Night Lights show Jazz Cameos, which features jazz musicians sitting in on rock records

- Read Stuart Nicholson's Jazz-Rock: A History

Listen to Mike Mainieri's 1968 album Journey Thru An Electric Tube:

- Peruse Jazz.com's pre-history of jazz-rock