In 1957 singer Ella Fitzgerald had one of her most prolific years on record, recording more than a hundred tracks with artists such as Louis Armstrong, Stan Getz, Duke Ellington, and Oscar Peterson, as her career continued to soar in the wake of signing with Norman Granz’s Verve label.

In 1957 Ella Fitzgerald turned 40 years old, and her star was on the rise again. She had first hit the jazz scene as a teenager singing with Chick Webb's popular 1930s big band, going on to solo stardom in the World War II years. She kept up a fair degree of success in the late 1940s and early 50s on the Decca label, but her career took a significant turn when jazz impresario and Fitzgerald manager Norman Granz signed her to his Verve label in the mid-1950s.

Granz wanted to pair Fitzgerald not only with other top-notch artists on Verve, but also with the works of jazz and popular song composers that would become known—in part because of the albums Fitzgerald would record for Granz—as the Great American Songbook. British jazz writer Benny Green would later observe that "her perfect intonation, natural harmony, vast vocal range, and purity of tone helped to make Ella's versions… the definitive versions." In 1956 she made double-albums of both Cole Porter and Rodgers and Hart songs, and then Granz teamed her up with Duke Ellington's orchestra.

Though Granz later complained that Ellington had not brought one new arrangement to the sessions, Ellington band members disputed his account when the Ellington songbook was reissued on CD in the late 1990s. Ellington and his composing/arranging partner Billy Strayhorn worked diligently with Fitzgerald in the studio, and the results, which featured the singer with both the Ellington orchestra and smaller groups led by Ellingtonians or ex-Ellingtonians, were the most swinging and natural-fit Fitzgerald songbook recordings yet:

In addition to working with Ellington, Fitzgerald also forged ahead in the studio with another jazz giant, Louis Armstrong. Norman Granz had brought the two together the year before for their first LP-length studio encounter, the hit album Ella And Louis, and in the summer of 1957, working around Armstrong's demanding schedule, he set up sessions for two more albums—one a double-LP songbook tour simply titled Ella And Louis Again, and the other a full treatment of George and Ira Gershwin's Porgy And Bess. Fitzgerald and Armstrong were perfect foils for each other, brimming with a genuine jazz-vocal rapport, playful and poignant in their renderings of songs we now know as standards:

1957 was also a somewhat tumultuous year for Fitzgerald; she moved from New York City to the West Coast, underwent an operation for an abdominal recess, bought a house, kept up a busy touring schedule, became the first black artist to headline at New York's Copacabana club, filmed a cameo as herself in the W.C. Handy biopic St. Louis Blues, was attacked onstage in Atlantic City by a deranged fan who also had the last name of Fitzgerald, and may or may not have married a Norwegian man named Thor Larsen. Whatever their status, the relationship, like others in Fitzgerald's life, ultimately didn't pan out. "I want to get married again," she told a New York Mirror reporter that June. "I'm still looking. Everybody needs companionship." "That's the missing note in her life," the reporter concluded. "Ella is just lonely."

She certainly didn't lack for professional activity. During the prolific Ella And Louis Again sessions, Fitzgerald and Armstrong each did a handful of tracks without the other. On this tour de force version of the ballad "These Foolish Things," Fitzgerald is accompanied by Oscar Peterson's trio and drummer Louis Bellson, who set the table for the singer with elegant restraint on a song that's aptly suited for the sense of dreamy longing that Fitzgerald conveyed so well:

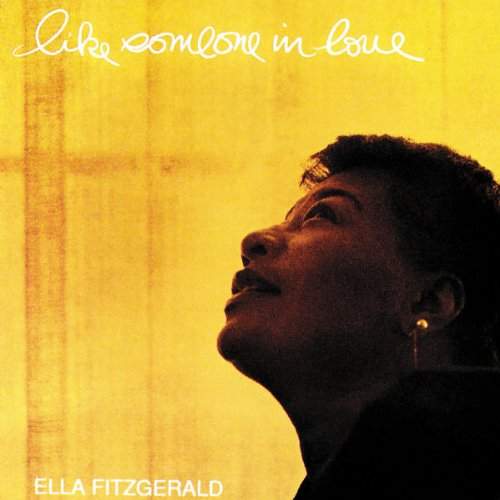

That same autumn Norman Granz managed to put Fitzgerald and popular tenor saxophonist Stan Getz in the studio together as well, working with arranger and conductor Frank DeVol. who'd had huge success with his musical rundown of "Nature Boy" for Nat King Cole, and who'd worked with Doris Day and Tony Bennett. In later years De Vol would also work as a TV actor and write the title themes for the TV shows "My Three Sons" and "The Brady Bunch." The goal was to emulate the Frank Sinatra concept LPs that had been coming out in the mid-1950s—albums that Sinatra made with arranger Nelson Riddle that established an LP-long mood, often either swinging or melancholic. The intended audience for Fitzgerald's LP, according to the liner notes, was "People in love," and the result, called Like Someone In Love, was one of those great 1950s drinking-wine-by-the-fireplace records:

While Fitzgerald was in Los Angeles that October, she also performed at the Shrine Auditorium as part of a Norman Granz Jazz at the Philharmonic concert, accompanied by the usual Granz suspects, such as trumpeter Roy Eldridge, saxophonists Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins, and the Oscar Peterson Trio. Fitzgerald herself was a mainstay of Granz's presentations, and we hear her here on a tune that evokes her 1930s swing-era days in Harlem with Chick Webb's big band:

That autumn's Jazz At The Philharmonic tour would prove to be the last one Norman Granz organized for America for some time. Fitzgerald would maintain her busy schedule, however, recording and performing, with some of her best work still to come in the years that immediately followed 1957. In their book Singing Jazz, Bruce Crowther and Mike Pinford observed that Fitzgerald's recordings of the late 1950s and early 1960s "achieved…a joyful symbiosis of those elements that can be appreciated and enjoyed by the non-jazz audience, and those elements of pop that are acceptable to jazz fans." By the end of her career she had recorded more than 1100 different songs, and in 1993, New York Times writer Stephen Holden summed up her appeal: "Singing in a style that transcended race, ethnicity, class, and age, she was a voice of profound reassurance. At the end of everything, there was always hope." And whatever loneliness Fitzgerald encountered in her personal life, the light of her spirit always shone through her singing. From 1957, here's Ella Fitzgerald and "Lost In A Fog," on Night Lights:

Ella '57 Outtakes

More Of 1957 On Night Lights