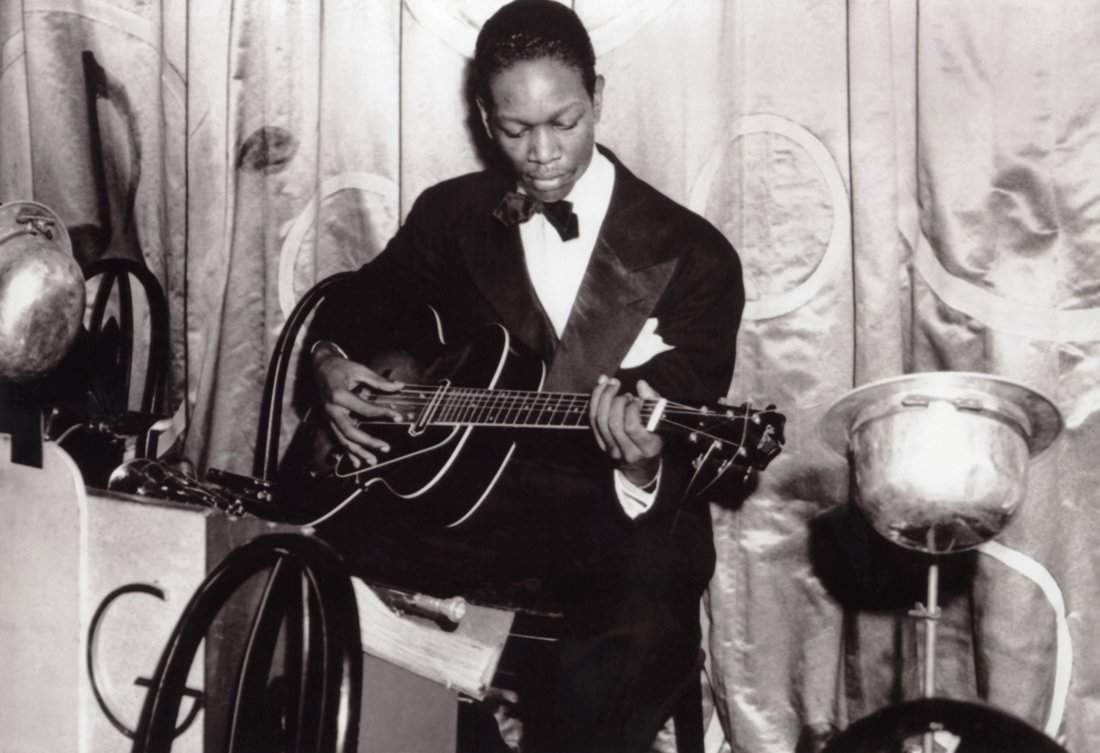

In 1939 a young musician named Charlie Christian seemingly came from out of nowhere to become a pioneer of the electric guitar in jazz and help pave the way for the rise of bebop, though he himself would not live to see it. On this edition of Night Lights we'll hear his swinging, scintillating solos with Benny Goodman, Thelonious Monk, Lester Young, and other significant artists of his time.

In 1939, the age when swing was king, the guitar was not the thing. The acoustic instrument was in danger of becoming lost in the world of large-ensemble jazz. The advent of Charlie Christian and his electric guitar changed all that, creating a path to follow for Wes Montgomery, Grant Green, Tal Farlow, George Benson, Barney Kessel, and many others. While Christian was not the first guitar soloist in jazz, with just a handful of musicians preceding him-Eddie Lang, Lonnie Johnson, and Django Reinhardt-and not the first to play electric guitar, either-in less than two years this thin, quiet, bespectacled young man made a series of recordings that put him in the echelon of jazz greats such as Lester Young and Charlie Parker, influencing guitarists to this day, and not just in jazz, either; in 1990 Christian was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, an acknowledgement of his far-reaching impact.

"Long, Flowing Bursts Of Lyrical Melody"

Charlie Christian was born in Bonham, Texas on July 29, 1916 and grew up in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. He and his brothers were taught to play music by their father, who became blind and relied on his sons to guide him to places where he could play for money on the street. Ralph Ellison, whose novel Invisible Man is considered to be a landmark of 20th century literature, knew Christian growing up and wrote an eloquent remembrance in 1958, evoking the guitarist's origins:

He flowered from a background with roots not only in a tradition of music, but in a deep division in the Negro community as well. He spent much of his life in a slum in which all the forms of disintegration attending the urbanization of rural Negroes ran riot. Although he himself was from a respectable family, the wooden tenement in which he grew up was full of poverty, crime, and sickness. It was also alive and exciting, and I enjoyed visiting there, for the people both lived and sang the blues. Nonetheless, it was doubtlessly here that he developed the tuberculosis from which he died.

Christian's father died when Charlie was 12, and he spent much of the 1930s playing with territory bands. He began to play an electrified guitar in the late 1930s, and his amplified approach won him a passionate following among area musicians. "The typical Christian solo," jazz critic Martin Williams wrote, "is organized in contrasts of brief, tight, riff figures and long, flowing bursts of lyrical melody; and in his best improvisations these elements not only contrast effectively but also, paradoxically, lead to another."

Christian's big break came when jazz impresario John Hammond, hipped to the guitarist's talent by pianist Mary Lou Williams, persuaded Benny Goodman, the so-called "King of Swing," to give Christian a chance at playing with his small group and big band. Christian was reluctant to leave Oklahoma City, and Goodman was reportedly lukewarm about bringing Christian aboard until a Hammond-arranged appearance on the bandstand led to a legendary, possibly apocryphal 45-minute rendition of "Rose Room." There's no doubt that Goodman was impressed, and soon Christian was both performing and recording with Goodman, often in the context of the small group, and often on tunes that incorporated riffs that Christian had brought with him from Oklahoma City. We'll hear one such tune now, the first studio recording that Charlie Christian made with Benny Goodman:

Christian's swinging, innovative and amplified sound immediately galvanized both listeners and other musicians, and in January 1940, after being on the national scene for just several months, he won DownBeat Magazine's reader poll for best guitarist. He participated in the second "From Spirituals To Swing" concert at Carnegie Hall, and was a frequent presence at jam sessions. The bulk of his recorded legacy comes from his small-group appearances with Benny Goodman, a dynamic where his lopes and bursts of melody had the best opportunity to shine. Christian's playing, writes jazz scholar Loren Schoenberg, "was all about the line and about how rhythm could extend the line and give it all sorts of new and unexpected shapes."

Almost all of Christian's notable solos with Goodman came in small-group settings, but he was featured from time to time on the full-orchestra recordings that he made with the clarinetist. We'll hear one of the recordings that's come to be associated strongly with Christian, called "Solo Flight," after this Fletcher Henderson arrangement of "Honeysuckle Rose":

Christian found some of his musical inspiration in Lester Young, another innovator whose sound left a significant stamp on many who followed. Christian was a teenager when he first heard Young, and there are accounts of him memorizing Young's solos and singing them to himself. Young, jazz critic Kevin Whitehead says, "profoundly influenced the guitarist's slingshot rhythms - the way he'd lag behind the beat and then spring ahead." Christian performed and recorded with Young on just a couple of occasions, including a 1940 studio date that brought the guitarist and Benny Goodman together with members of Count Basie's orchestra. Curiously, this session was not released at the time, possibly because of internal jazz-world machinations involving Basie and Goodman; the music itself is stellar. On the first selection Goodman sits out while the others play a dreamy blues; then, at the beginning of "Wholly Cats," listen for Goodman exhorting "C'mon, Charlie" right before Christian's solo.

Record buyers got a rare chance to hear Christian on acoustic guitar after he participated in a February 1941 quartet date for the then-fairly new Blue Note label led by clarinetist Edmond Hall, with Israel Crosby on bass and Meade Lux Lewis playing celeste. Of this recording Martin Williams wrote,

"Profoundly Blue" opens with three superb Christian choruses, with Crosby in a true countermelody behind him, and with a few gently rendered comments from Lewis as well. It is a performance of such exceptional musical and emotional quality as to produce a sense of sustained wonder, both the first time one hears it and the hundredth.

Only a couple of months after that session, Christian was captured on a disc-cutting recording machine at Minton's, a club in Harlem that has passed into jazz legend as a place where young musicians such as Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie gathered to jam. It is often cited as the place where bebop was born. And while the story of bebop's origins is considerably more complex, the creative opportunities and artistically challenging environment that Minton's offered played an important role in the evolution of a new sound for jazz. Charlie Christian, who would spend much of the last year of his life battling tuberculosis, would not live to see or hear the full flowering of bebop in the mid-to-late 1940s, but the recordings made at Minton's give us a chance to hear how far ahead of his time he already was. As jazz critic Kevin Whitehead observes, "His amped-up rhythms and offbeat accents fit right in" with the sound of the future. We'll hear him here on a version of the tune "Topsy," later retitled "Swing To Bop," on Night Lights:

Charlie Christian and "Swing To Bop," actually a variation on the tune "Topsy," recorded at Minton's in Harlem in May of 1941, with Thelonious Monk thought to be the pianist, although some scholars disagree and suggest that it's Kenneth Kersey.

The May 1941 Minton's jam sessions are close to the last times that Charlie Christian's guitar playing was ever recorded; shortly afterwards, with his health worsening as a result of tuberculosis, and possibly aggravated by the hectic, late-night lifestyle of the jazz world, he was admitted to Seaview Hospital on Staten Island. Over the next few months he was frequently visited by friends, and by one account he and another hospitalized musician organized jam sessions to entertain patients who were too sick to leave their beds. Reports in the music press of his condition gave a mixed view as to whether he was recovering or getting worse, but on March 2, 1942, Charlie Christian passed away at the age of 25. "Charlie Christian Dies In New York," a headline announced in the March 15, 1942 issue of DownBeat Magazine. The article also indicated that trumpeter Cootie Williams had been planning on adding Christian to his new band. Another great innovator on his instrument, bassist Jimmy Blanton, would die of tuberculosis just a few months later at the age of 23. America and the world had plunged into war, the big-band era had less time left than its leaders could have imagined, and in just 15 years the electric guitar would become the primary instrument of popular music. Charlie Christian wouldn't be around to hear it, but the music that he played in the short span of less than 24 months, between the autumn of 1939 and the spring of 1941, continues to reverberate down through the ages to today:

Night Lights After Hours With Charlie Christian

- A comprehensive collection of Christian's classic studio recordings

- Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead's centennial appreciation of Christian

- A transcription and analysis of Christian's "Stompin' at the Savoy" solo and much more

- Peter Broadbent's hard-to-find Charlie Christian biography