Throughout the history of jazz many superlative musicians have failed to earn the recognition that they deserved, but jazz critic Gary Giddins has said that the name of one artist in particular has become "virtually synonymous with underrated"--and that artist is trumpeter Kenny Dorham.

Dorham, whose playing has been described by one writer as having "a bittersweet glow," was born in Fairfield, Texas in 1924. He told an interviewer in 1962 that he came to his love of jazz through his sister, who used to sing commercials around the house, brought home Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway records, and bought Dorham a trumpet when he was 15.

After some time in the Army in the 1940s and a brief flirtation with a boxing career, Dorham broke into the big-band scene, working with Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine, and Lionel Hampton. In the late 1940s he got his first high-profile small-group gig playing with Charlie Parker, replacing the youngMiles Davis, and also made a number of dates with other young, up-and-coming bebop musicians.

Dorham‘s early musical conception and playing skills were not necessarily on a par with compatriots like Gillespie and Fats Navarro, but some early recordings give an indication of where he was headed. We‘ll hear two of them on the show--one a radio broadcast of "Barbados" with Charlie Parker, and a studio date with the Bebop Boys doing "Blues in Bebop."

From Bebop To Hardbop

As bebop became a more standardized sound in the early 1950s, jazz artists began looking for new approaches that resulted in the styles known as Latin or Afro-Cuban jazz and hardbop jazz. Kenny Dorham made his own contributions to these emerging sounds, particularly with his album Afro-Cuban and his time as a member of the seminal hardbop group Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers--a gig that allowed Dorham to leave his day job working at a sugar refinery.

In 1955 the Jazz Messengers made a live recording at Café Bohemia in New York City, with Blakey introducing Dorham as "the uncrowned king." The tunes they played included a composition Dorham had penned for the Afro-Cuban album called "Minor‘s Holiday." "That horn section was so hip, you know, they were super hip," pianist Horace Silver said years later of Dorham and saxophonist bandmate Hank Mobley. "The way they phrased, and the lines they played, their harmonic knowledge was so beautiful."

Just a few months later Dorham returned to Café Bohemia, this time as the leader of a new group, the Jazz Prophets--a name undoubtedly chosen to trade in on the rising recognition of the Blakey group Dorham had just left. He enlisted young, up-and-coming musicians such as guitarist Kenny Burrell, pianist Bobby Timmons, and saxophonist J.R. Monterose, and took the band into the studio twice, for an album that came out on ABC-Paramount and a followup that was never released and has been lost. The band was also recorded at Café Bohemia by Blue Note, and the two-CD set of those recordings is the group‘s most extensive audio documentation.

Ultimately, though, it was a brief run for the Jazz Prophets. Years later Monterose told a jazz journalist that

Kenny Dorham is a wonderful person. He‘s a very vital person, and he has a lot of warmth, and all the time I was with him I listened to every note he played… I had many, many very rewarding experiences with Kenny, and I was sorry to see the association end when it did; but it was just the economic situation, as it usually is.

An Emerging Leader

In a 1958 DownBeat blindfold test headlined "Durable Dorham," Leonard Feather wrote that "Kenny Dorham is almost the only sideman left in jazz. In these days when everyone, down to the last bass player and drummer, has his own recording contract, Dorham is almost an anachronism. Except for an occasional LP of his own, he has gone through the years… always respected and admired, but never winning any polls and never going out after individual fame as a leader."

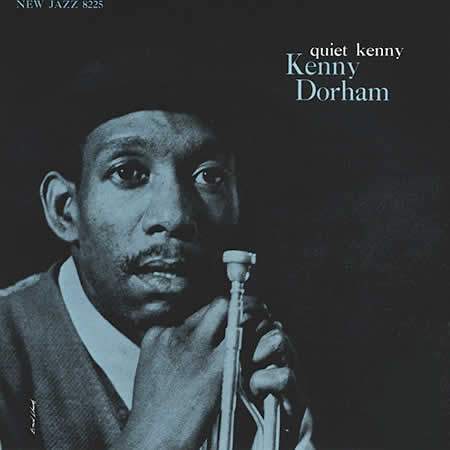

Around that time, though, Dorham finally managed to launch a run of albums under his own name, including one that featured the trumpeter singing as well. LPs like Quiet Kenny and Whistle Stop showcased Dorham‘s growing skills as both a composer and a player and increased the esteem that he already enjoyed from his fellow musicians.

In the early 1960s Dorham began to record frequently for Blue Note with one of his most significant musical partners--saxophonist Joe Henderson. Jazz writer Bob Blumenthal says that Dorham and Henderson "resonate as a pair like Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker," and Henderson himself, then an up-and-coming young artist, told Nat Hentoff, "We have some kind of vibration going." The two recorded together on six different albums and waxed several Dorham-penned tunes that have made their way into the jazz canon, including "Blue Bossa" and "Una Mas." A nightclub recording of the latter tune recently surfaced, and Blumenthal calls it

populist jazz with substance, and an ideal forum for contrasting Dorham and Henderson‘s approach to pacing, invention, and expressive tonality. The trumpeter stays closer to the melody, using shading to excellent effect, while Henderson pecks and feints as the pressure builds to some of his most effective agonized phrase wresting.

"A Beautiful, Romantic Sound"

As the 1960s went on Dorham became one of the first jazz musicians to actively work as a critic as well, writing record reviews for DownBeat. He and Joe Henderson also led a big band that sadly was never recorded, and he appeared on one of the landmark jazz albums of the era, pianist Andrew Hill‘s Point Of Departure. In the liner notes to that LP Hill said

I consider Kenny to be the most underrated player in the business. His problem is that he‘s so nice, and people seem to associate greatness with meanness or bitterness. In this business you have to create some kind of angry or tough image of yourself to be accepted, and therefore, too many people take Kenny for granted.

In the late 1960s Dorham went back to school, pursuing a master‘s degree in music through New York University, and wrote about the growing role of jazz education for DownBeat. But his career and life were ultimately be cut short by a debilitating kidney disease, and he died at the age of 48 in 1972. In its obituary DownBeat Magazine stated that

Kenny Dorham was a unique artists whose style matured relatively late but then continued to develop and blossom… Increasingly, his improvisations were based as much on the melodic as the harmonic aspects of the material, and his tone, always pretty, became a beautiful, romantic sound--among the most beautiful in modern jazz.

That tone was captured one last time in a studio in December of 1968, when Dorham did what would prove to be his final session with saxophonist Cecil Payne. We conclude this edition of Night Lights with "Follow Me" from that valedictory recording date.

Watch Kenny Dorham performing live in Stockholm in 1963: