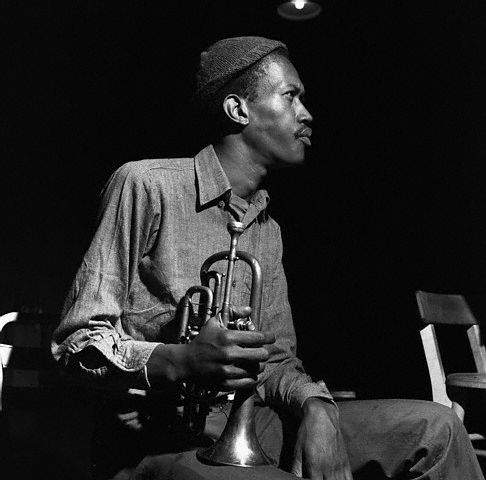

Cornetist Don Cherry first came to note in the jazz world at the end of the 1950s, playing in saxophonist and avant-garde pioneer Ornette Coleman‘s quartet; but Cherry would spend the 1960s making his own musical way, first as a sideman with other artists such as Sonny Rollins and Albert Ayler, and then as a leader in his own right.

Cherry was born November 18, 1936 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and grew up in Los Angeles, where he first started playing trumpet, as well as piano. Under the spell of bebop and hardbop trumpeters such as Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, and Miles Davis, he had a life-changing experience when he met Ornette Coleman in an L.A. music store in 1956 and became a key musical companion. "He had long hair and a beard," Cherry later recalled. "It was about 90 degrees, and he had on an overcoat. I was scared of him." The music the two would ultimately make together would scare many others in the jazz world just several years later.

Spare And Contradictory

Cherry‘s style as a trumpet player has often been described as spare or fragmented… terms that can easily sell short his use of space and his melodic and rhythmic inventiveness, which early on began to roam far beyond the confines of bop. He would also adopt a small b-flat Pakistani pocket trumpet as his primary instrument… but eventually he would record and make music on all sorts of instruments, all in the service of an expanding aesthetic vision. In his book Free Jazz, Ekkehard Jost writes

The essence of Cherry‘s music lies in its contradictions. It is at once humorous and melancholy, full of pathos and fun, energy-laden and meditative, songlike and chaotic, complicated and simple.

Post-Coleman Collaborations

By 1961 Ornette Coleman was heading into a period of slowed-down performing and recording activity. Don Cherry eventually found himself partnering with another high-profile saxophonist, Sonny Rollins, who was emerging from his own sabbatical, and who wanted to take his music in a direction that responded to Coleman‘s high-impact free jazz influence. One good way to do that was to hire Coleman‘s trumpeter.

After departing Rollins‘ group, Cherry became a part of a young avant-garden ensemble called the New York Contemporary Five, which including saxophonists Archie Shepp and John Tchai, and drummer Sunny Murray. Cherry had won the 1963 Downbeat New Star trumpeter award, rather ironic in light of his presence on the scene for several years; but as Leroi Jones noted in a Downbeat profile, Cherry was having a hard time finding work. Jones blamed this on Cherry‘s "fresh" and "singular" style being too discomforting for many club owners and jazz fans. Cherry had made a very compelling trio date for Atlantic with Henry Grimes and Ed Blackwell, but to this day it remains unreleased. So the opportunity to play with the New York Contemporary Five was a timely one for Cherry, and Jones spoke of the group‘s promise with enthusiasm in his Downbeat piece.

When Cherry Met Ayler

Cherry also spent some of this time working in Europe with saxophonist Albert Ayler, yet another groundbreaking saxophonist. It‘s amazing in retrospect to consider that Cherry was a front-line partner with Ornette Coleman, Sonny Rollins, and Albert Ayler, and that he also made a record date at the start of the 1960s with John Coltrane--music from which can be heard on the Night Lights show The Ornette Coleman Songbook. In his book THE FREEDOM PRINCIPLE: JAZZ AFTER 1958, critic John Litweiler discusses one Cherry/Ayler recording, saying

In the way Cherry commented upon Sonny Rollins, he became a leavening agent in Ayler‘s music, too. His blasts of punctuation, his joining in ensemble improvisations, his broken-phrase responses lend the music the intimacy of sympathetic, recognizable emotion, as opposed to Ayler‘s extravagance. The slow "Mothers"demonstrates Ayler and Cherry creating a unity out of their divergence…. Much of Cherry‘s ensuing solo is a haunting, clear-toned statement emphasizing the theme‘s yearning lyricism without Ayler‘s grotesquerie; after Ayler has returned, there is a bridge in which Cherry‘s low tones rise to an interlude of bright, quick trumpet against the stately, obese sax. Self-pity is a most unlike source for, of all things, a major jazz performance; even so, "Mothers" is one of Ayler‘s finest works.

Cherry‘s path through the decade crossed continents and converged with many other artists, and jazz researchers are still trying to retrace his physical and musical journeys. As one musical comrade from that period noted recently, a book really needs to be written about this phase of the trumpeter's career. Stateside, Cherry recorded several albums for the esteemed Blue Note label that would become a building block of his 1960s musical legacy, and the start of an exciting and creatively vital period for Cherry. As Ekkehard Jost noted in his book Free Jazz,

a little-noticed jazz veteran proceeded to introduce into the music of the second free-jazz generation creative ideas that went far beyond what he had learned as a sideman with Coleman, ideas which had a decisive influence upon the evolution of that music.

The Cherry Blue Note album Complete Communion‘s contribution was to introduce the idea of formal and thematic organization to an extended free-jazz composition.

Cherry would perform some of his Blue Note music live in Europe around this time, with Gato Barbieri still on sax, but with a European rhythm section. Bassist Cameron Brown, who played with the group for awhile, recalled decades later that

I was just like the guy hanging on for dear life. That band was so tight. They played the whole history of the music. It was amazing. They‘d be playing an Ornette tune, and then they‘d play "How Insensitive," and then they‘d be playing some wild Albert Ayler tune, and then they‘d play "Two Bass Hit." It felt unbelievable; the creativity and how quickly the whole band would just sort of go with Don to the next tune.

A number of the group‘s performances were recorded and have been surfacing in recent years; one such performance, "Remembrance," recorded live in Copenhagen in 1966, is featured in this show.

World Beyond

Don Cherry would reunite briefly with Ornette Coleman at the end of the decade, and he would cut several more albums that are now hard-to-find free-jazz masterpieces, including an album of duets with drummer Ed Blackwell and the live album Eternal Rhythm. He would also make a live recording at the U.S. Embassy in Turkey, that shows his increasing interest in world music-an interest that would continue to manifest itself in the musical paths Cherry followed throughout the 1970s. We close the program with Don Cherry performing some Turkish folk music at the end of the 1960s.