Veteran jazz producer and radio host Bob Porter defined soul jazz as "the music of the organ players, the tenor players, and the funky piano players from the late 1950s to the early 1970s."

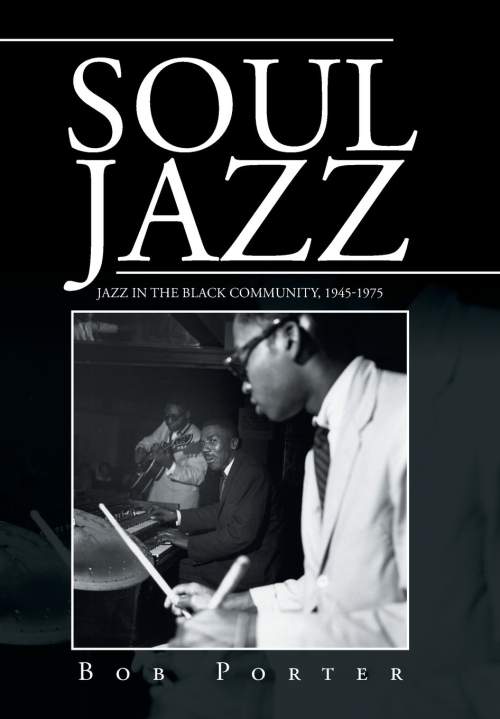

From the late 1940s to the early 1970s, the simmering funk and grooves of soul jazz evolved into one of the music's most popular styles, often driven by organ combos featuring guitarists such as George Benson and Grant Green. On this edition of Night Lights we'll hear recordings by some of the genre's leading artists and talk with veteran producer Bob Porter, author of the book Soul Jazz: Jazz In The Black Community 1945-1975.

Once upon a time in black America soul jazz was one of the driving musical forces in the clubs and on the jukeboxes, in the record stores and on the streets, with good grooves and cooking lines that conveyed a blues-soaked vitality and formed a bridge from the R and B and jump blues of the late 1940s and early 50s to the soul-music movement of the 1960s and beyond. Bob Porter, who produced LPs by many soul-jazz artists in the late 1960s and early 70s, offers his definition of soul jazz:

It's the music of the organ players, the tenor players, and the funky piano players from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. That's the period of its greatest popularity.

Porter traces soul-jazz's roots back to the mid-1940s, when tenor saxophonist Illinois Jacquet, who had first made a name for himself with his high-atmosphere soloing on Lionel Hampton's "Flyin' Home," put together a popular octet often referred to as the Little Big Band:

While the brawny tenor saxophone sound of musicians like Jacquet would end up playing a significant role in the evolution of soul jazz, an even more significant factor was the ascendancy of the organ combo, fueled in particular in the mid-1950s by organist Jimmy Smith's great leap forward on the instrument, and by groups such as that of saxophonist Eddie Lockjaw Davis and organist Shirley Scott. Usually in conjunction with drums and sometimes a guitar or bass, these small groups gained great popularity both on records and in the clubs of the black community. Bob Porter cites economics and the uniquely earthy, church-goes-to-the bar sound as factors in the rise of the organ combo.

Despite the success of soul jazz in the black community, it didn't always garner much coverage in the jazz press early on, as Bob Porter notes, singling out saxophonist Willis Jackson as one popular artist who was rarely mentioned in the late 1950s and early 60s. He says that the attention the music did gain from magazines such as DownBeat was often derisive: "I could almost predict in advance what certain critics were going to write."

One of the most successful soul-jazz artists was tenor saxophonist Gene Ammons. Though a drugs-related incarceration kept Ammons off the scene throughout much of the 1960s, Porter says that the Prestige record label worked to keep his name in the public eye with staggered releases of previously-recorded material while he was in prison. Ammons returned while the soul-jazz movement was still going strong at the end of the decade:

Though record sales were clearly of economic importance to artists and producers such as Ammons and Porter, as well as the record labels, you could find the soul-jazz scene at its most vibrant in the clubs. Porter frequented two clubs in Newark, New Jersey in particular, Club Cadillac and the Key Club, that were across the street from each other. Here's saxophonist Lou Donaldson at Club Cadillac, with a rhythm section that Porter dubbed "the Mod Squad," with Leon Spencer Jr. on organ, Melvin Sparks on guitar, and Idris Muhammad on drums:

Soul jazz would peter out across the course of the late 1970s and 80s, a victim of changing musical trends and environments, though it remains an influence on modern-day jazz artists and retains a cult following among listeners around the world. Bob Porter's book Soul Jazz brings us many of the musicians and much of the history of a long-gone scene-a scene that he evokes at the end of the show as he recalls what it was like to walk into Newark's Key Club on a busy night. We close with a live 1970 performance from that club by organist Charles Earland's group:

Soul Jazz: The After-Hours Set

- Soul Jazz: Jazz In The Black Community 1945-1975 (Bob Porter's book)

- Bob Porter on Soul Jazz (JazzWax blog post)

- Bob Porter on organ combos (JazzWax blog post)

Outtakes:

Charles Earland, "Black Talk":

Special thanks to Bob Porter and Casey Zakin.