James Moody was a compelling artist, a down-to-earth entertainer, and a human being almost universally known as a genuinely nice person.

Jazz writer Gary Giddins once described the essence of James Moody's playing as "passion, lyricism, control, distance, unpredictability, wit, and tonal variation"-but such artful mastery of music probably seemed unlikely when Moody was born partially deaf in Savannah, Georgia in 1925. Growing up in Newark, New Jersey, he began to play saxophone, and eventually he'd shift among tenor, alto, and soprano, in addition to playing flute; on all instruments he favored the low and middle registers because of his hearing defect, which made hearing high notes difficult.

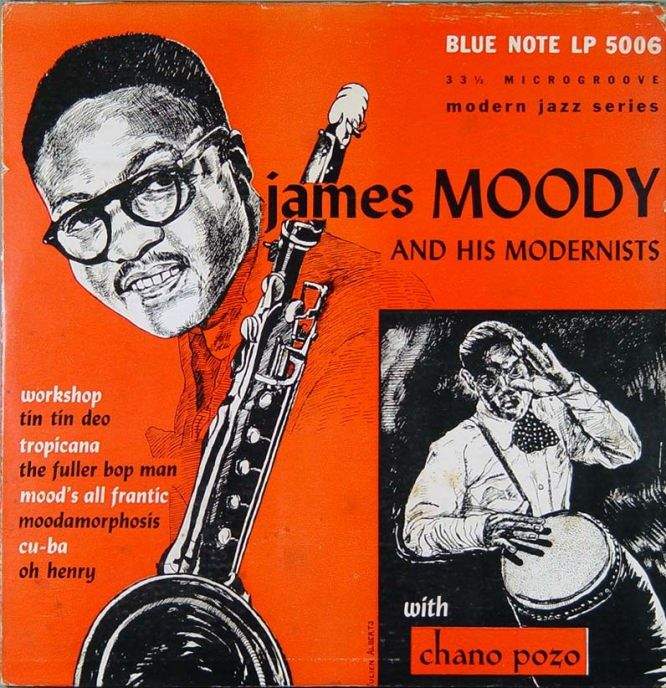

In the early 1940s Moody served in a segregated unit of the Air Force and met Dizzy Gillespie at a military-base concert, where he was invited to audition for Gillespie's big band after his discharge. Steeped in the influences of mid-1940s bebop, Moody would forge one of the most significant musical partnerships of his career when he finally joined Gillespie's orchestra in 1946. His first recorded solo with the band, on "Emanon," gained him some early recognition…saxophonist Jimmy Heath later said,

Moody's 'Emanon' solo was very exciting to all the saxophone players around Philadelphia. It was very different than any blues solo that you had heard. He had the bebop sound.

Starting Over: In Europe and After Overbrook

James Moody moved to Europe at the end of the 1940s-partly, as he later said, to try to deal with his growing dependence on alcohol and Benzedrine. That dependence would dog Moody throughout the 1950s while he led a successful bop and R-and-B styled band, until a six-month stay at Overbrook Hospital in New Jersey in 1958 enabled him to get a fresh and sustained start.

Moody stayed in Europe from 1949 to 1951 and made a number of recordings, among them a version of Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields' "I'm in the Mood for Love" that featured him on alto sax, which he would also play throughout his career as well as tenor… "I'm in the Mood for Love" would become a signature piece for Moody after singer King Pleasure scored a hit stateside with a vocalese take based on Moody's performance, with lyrics penned by bop-vocal virtuoso Eddie Jefferson. We'll hear Moody's original recording of it, and we'll also hear "Last Train From Overbrook," a Moody composition written near the end of the 1950s, and titled in tribute to the hospital where he was able to finally recenter his life.

Moody and Dizzy

In the early 1960s Moody renewed his musical association with Dizzy Gillespie, replacing Leo Wright in the trumpeter's quintet and staying throughout much of the decade. Gillespie biographer Donald Maggin writes that

Moody's improvisations displayed greater harmonic sophistication, he had mastered a broader range of sounds and colorings to express his emotions, and he projected more passion. In addition, Moody possessed comedic talents and became an apt foil in several of Dizzy's humorous routines.

"Playing with Moody is like playing with a continuation of myself," Gillespie once said, and Moody would later say, "I felt the same way with him. He was my mentor, my teacher, my best friend, and my brother."

The 1960s Onward

Like many jazz artists who'd come into their own during the bebop era, Moody professed less-than-positive thoughts about the free jazz movement of the 1960s. In a 1968 Downbeat blindfold test he remarked of an Albert Ayler record, "That sounded rather like ‘No Place Like Home' and that's where they should have been." But Moody was listening to jazz of the day, especially to John Coltrane's advances, and years before he'd worked hard with bandmate and arranger Tom McIntosh to develop his harmonic skills and knowledge. His jibes at the avant-garde aside, his records from the late 1960s on gave evidence that he had kept his ears and his mind open. Reviewing Moody's 1969 album Don't Look Away Now, critic Larry Kart wrote, "It sounds as though he's saying, ‘Watch me get into this and back to my other things without a hitch."

Moody spent much of the 1970s playing in the Las Vegas Hilton Orchestra, backing performers such as Elvis Presley, Bill Cosby, and Liberace. But before taking on this gig for economic security, he made two stellar albums for the Muse label, Never Again and Feelin' It Together. From the latter we'll hear an unusual arrangement of Antonio Carlos Jobim's "Wave" that also gives us a chance to hear Moody playing flute. Moody had started playing flute in the 1950s after buying one from a man on the street for $30…and though he liked to describe himself as a "flute-holder" rather than player, he became one of the most respected flutists in jazz.

James Moody performed and recorded almost right up to the time of his death in December 2010. Fellow saxophonist Sonny Rollins acknowledged the sadness of the loss and said,

But it's also really a joyful moment because he was here in this life and look what he left people, a legacy of wonderful music and the memory of a wonderful person. To know him and think about him brings light to me. We can't feel sad or sorry. We have to feel good about a man like Moody.

Singer Roberta Gambarini recalled Moody's ongoing interest in younger players; once, she said, he approached a young saxophonist and asked him if he could show Moody how he achieved a certain effect, to which the saxophonist replied, "But Moody, I got it from you!"

The program closes with Moody's 1988 recording of a John Coltrane jazz standard, the complex wonders of which Moody raved about in a 1972 Downbeat interview. "In time though, ‘Giant Steps' will come to be like ‘Exactly Like You," Moody said, citing a swing-era standard. "I just wish I could be around to dig it. The way kids are today…they're very inquisitive, they want to know…Oh, Lord, do me this favor-let me stick around and cut this last chorus and then, then-maybe I could catch the next chorus too?"

More Moody

- NPR's A Blog Supreme's Moody Remembrance

- The New York Times' Moody obituary

- Detroit Free Press critic Mark Stryker's 2010 interview with Moody

Watch James Moody and Dizzy Gillespie in 1965: