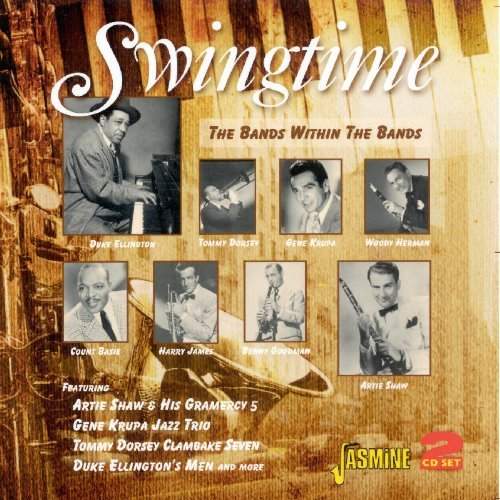

Once upon a time, big bands ruled the land in America. Within those bands, however, there were little bands-units that gave orchestra leaders and their sidemen the opportunity to play in looser or different styles, and to give their onstage act some variety.

Goodman Leads The Way

The "band-within-a-band" concept might be traced all the way back to a landmark 1924 Paul Whiteman concert, which featured a small group playing the music of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, but its most significant pioneer was clarinetist Benny Goodman. The Benny Goodman small group came about after jazz impresario and talent scout John Hammond heard Goodman and pianist Teddy Wilson jamming at a private party in 1935. Hammond suggested that Goodman‘s record label record the clarinetist and the pianist together, and Goodman added his band drummer Gene Krupa to form a trio. Eventually vibraphonist Lionel Hampton joined to make it a quartet.

Although Krupa was the only working member of Goodman‘s larger band, the Goodman trio and quartet became quite popular and was seen by the public as an extension of the clarinetist‘s orchestra. Its success helped pave the way for the rise of other small groups piloted by big-band leaders such as Tommy Dorsey, Bob Crosby, and Cab Calloway. The Goodman group crafted a swinging, early version of what would later be called "chamber jazz," filled with lively improvisation by Goodman and the other soloists, and it made another significant contribution as well--it was jazz‘s first ongoing interracial configuration. Several years later Goodman would expand the group to a sextet and introduce yet another significant development: electric guitarist Charlie Christian.

Tommy Dorsey was another successful 1930s bandleader who formed a small group, and the first to do so by drawing exclusively on his own orchestra members. His Clambake Seven unit, featuring standout players such as saxophonist Bud Freeman and drummer Dave Tough, played jazz with a Chicago and New Orleans flavor, a contrast to the larger band‘s more commercial approach, and still capable of yielding hits such as its inaugural recording "The Music Goes Round and Round." The Clambake Seven also became a part of the Dorsey orchestra‘s live performances.

The Ellingtonians

Perhaps nobody was better suited to create bands-within-a-band in the 1930s than Duke Ellington, who counted numerous talented musicians with unique voices and leadership desires of their own among his orchestra members. By the mid-1930s the Duke had already featured small groups within his larger band on a number of occasions, both in concert and in the studio, but his incredible run of late-1930s small-group dates was spurred on by a desire to make cheaper-priced records for the emerging jukebox trade.

Between 1936 and 1940 Johnny Hodges, Cootie Williams, and other Ellington artists would record enough small-group music to eventually fill a 7-CD box-set. They were billed by different names such as "Cootie Williams and His Rug Cutters" or "Barney Bigard and His Jazzopators," and they reflected the musical personalities of their leaders, though they all also sounded indubitably Ellingtonian, full of swing and creative color. Some of the recordings became hits, such as Johnny Hodges‘ "Jeep‘s Blues," or provided templates or reworkings of songs recorded by the larger orchestra.

1940s Big-Band Little Bands

In the case of drummer Gene Krupa, a working small group came about as the result of an argument at an orchestra rehearsal about tempos. Frustrated, Krupa sent everybody home except for pianist Teddy Napoleon and saxophonist Charlie Ventura, using the remaining studio time to record a song, "Dark Eyes," that would go on to become a hit for Krupa, leading to many more jazz trio recordings. It was quite a change at the time for the drummer, who‘d just given up on his outsized "Band-That-Swings-With-Strings" concept, but as a veteran of the 1930s Benny Goodman small group, he was certainly at home in the format.

One of the most notable bands-within-a-band was Artie Shaw‘s Gramercy 5. By 1940 Shaw was featuring several different scaled-down configurations in his performances, with their names all taken from New York telephone exchanges: Chelsea 3, Regent 4, Gramercy 5, etc. Shaw said that he formed the groups because he wanted to be able to improvise more freely than he could with the larger orchestra, but that only the Gramercy 5 was worthy of recording. One of the things that made it unusual was Shaw‘s use of a harpsichord, played by pianist Johnny Guarnieri. Shaw would resurrect the group in 1945, this time with bebop pianist Dodo Marmarosa and trumpeter Roy Eldridge, and he would lead yet another version in the early 1950s.

The king of the 1940s "band-within-a-band" configurations might have been Major Glenn Miller. His massive, World War II Army Air Force musical outfit, with 60 members in all, gave Miller the chance to make most of his listeners happy in one way or another, with the easy-listening Strings With Wings ensemble, the Swing Shift big band, singer Johnny Desmond and the Crew Chiefs vocal group, and more.

Miller maintained his musical authority over the various components of the AAF, but he did give free reign to one musician--the young pianist and arranger Mel Powell, who led the AAF‘s Uptown Hall Gang, a small, modernistic group that included clarinetist Peanuts Hucko, Addison Collins Jr. on French horn, and Nat Peck on trombone. The Uptown Hall Gang was Miller‘s nod to those seeking a "hipper" form of jazz, and it included among its repertoire a song that had was barely known yet to the general public--Dizzy Gillespie‘s bebop anthem "A Night in Tunisia."

This edition of Night Lights closes with music from Woody Herman‘s Woodchoppers, a small, bop-happy ensemble that grew out of the clarinetist‘s mid-1940s First Herd. Herman had recorded small groups within his orchestra before, but the Woodchoppers crackled with modernistic vitality and featured superlative soloists such as trumpeter Sonny Berman, saxophonist Flip Phillips, trombonist Bill Harris, and pianist Jimmy Rowles. The group also provided writing opportunities for the young trumpeter Shorty Rogers.