In the big-band era of the 1930s and 40s, radio networks frequently broadcast orchestras from hotels and ballrooms in big cities such as New York and Chicago, and the broadcasts could sometimes be heard by listeners hundreds of miles away. If you‘d tuned into NBC‘s "Blue Network" one night in February of 1942, you would have heard a Midwestern big band playing at the Savoy Ballroom in New York City--and you wouldn‘t have known it, but a young man who was going to change the course of jazz in just a few years was soloing in the orchestra that evening. The young man was alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, and we‘ll hear him at length near the end of the track that opens this show, on Jay McShann's "St. Louis Mood."

McShann's orchestra, one of the first big bands that Parker joined, came from Parker's hometown of Kansas City. It was one of the last great groups to emerge from that city's thriving 1930s scene that had produced bands such as Count Basie‘s. The airshots at the Savoy ballroom in February 1942 give us the chance to hear Charlie Parker stretching out a bit more than he could on 78 records, when he was an unknown, up-and-coming artist in his early 20s, already making huge strides in his approach to playing saxophone, but so far impressing mostly only a small circle of fellow musicians.

Bird In Big Bands, Off The Record

Over the next few years Charlie Parker somehow managed to pass through several other orchestras without being recorded. He left Jay McShann‘s band in 1942 and was persuaded by another young musician on the rise, Dizzy Gillespie, to join Earl Hines‘ orchestra. That particular edition of the Hines band became legendary for its personnel and sound, but unfortunately Parker‘s stay in it coincided with the American Federation of Musicians‘ recording ban, so there are no studio recordings and no known broadcasts of the band that survive.

In 1944 Parker joined the ranks of singer Billy Eckstine‘s progressive orchestra, which included, at one time or another, Dexter Gordon, Gene Ammons,Fats Navarro, Sonny Stitt, Miles Davis, and Art Blakey. However, the band never recorded while Parker was in it. Later on in the 1940s Parker played and rehearsed a few times with Dizzy Gillespie‘s big band, but once again the band was never caught on air or in the studio with Parker as a member.

The Norman Granz Years

The next chance we get to hear Parker in a large-ensemble setting comes in 1947, when Parker made some recordings for jazz impresario Norman Granz‘s Jazz Scene anthology. The Jazz Scene was sort of an early coffeetable package set, featuring 78s by a variety of artists in folio packets and a booklet as well, selling for $25--quite a steep price in the late 1940s. Parker did a small-group side for the set, but also rather spontaneously ended up appearing on a track put together by arranger Neal Hefti, called "Repetition." One of the orchestra members said years later that

It was the most phenomenal thing I ever saw. The lead sheet for him was spread out, a sheet of about ten pages and he had it strewn out over the piano. He was bending down then lifting his head up as the music passed by, reading it once or twice until he memorized those changed and then proceeded to become godly.

Parker spent the rest of his life recording for Granz‘s various labels, and Granz liked to feature him in a variety of settings--including, on several occasions, large-ensemble Latin-jazz dates. One such encounter

in 1948 paired Parker with Machito‘s Afro-Cuban big band. As Parker biographer Carl Woideck has observed, the simplicity of the one-and-two chord vamps often employed by Latin jazz bands like Machito‘s contrasted greatly with the quickly shifting key centers of much bebop repertoire at the time, potentially making creative improvisation more of a challenge for a player like Parker. As he so often did, however, Parker rose to the occasion. By 1948 he was already searching for formats that would force him to find new ways of being musically creative.

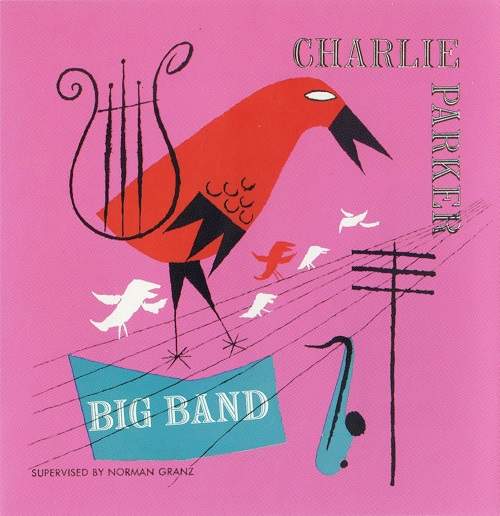

Recording with strings was yet another context for Charlie Parker during his time with Norman Granz… and while the with-strings recordings proved to be controversial with some Parker fans, in particular because of the rather saccharine arrangements provided by Mitch Miller, they indirectly led to some big-band studio recordings that Parker would make under his own name in 1952. Of all of his with-strings sides, Parker was happiest with those arranged by a pianist named Joe Lippman, and it was Lipman who did the charts for the 1952 big-band dates.

Lipman had gotten his start in the 1930s arranging for Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and Bunny Berigan--he‘s the one who did the arrangement of Berigan‘s signature hit "I Can‘t Get Started." He and Parker seemed to click; as jazz musician and scholar Bill Kirchner wrote about their recordings together,

The arranger knew that for best results he simply had to write conductor parts for Parker with a melody, chord changes, and indications about where to play or not play. After one or two hearings of an arrangement, the saxophonist‘s innate musicality took over.

One of the sides they produced, "Autumn in New York," became one of the best-selling records of Parker‘s career.

Guest Stints With Herman, Kenton, And The Orchestra

This studio big-band date of Parker‘s had been preceded a few months earlier by a concert appearance with the Woody Herman orchestra in Parker‘s hometown of Kansas City. According to the remembrances of one Herman band member, Parker was in town to visit his mother, and because of this was also sober, resulting in a crackling level of performance. He already knew much of the band‘s book, though in the second song of this set you‘ll hear him struggle a bit the first time through the bridge on the big-band-bop anthem "Four Brothers." He burns through "Lemon Drop," another flagwaver from the Herman orchestra's repertoire.

That same year a group of Washington D.C. jazz musicians put together a big band that they named in honor of a young, up-and-coming area jazz DJ--Willis Conover, who would go on to become famous around the world as a jazz host for the Voice of America. "Willis Conover Presents the Orchestra" put on a series of concerts that featured guest soloists such as Zoot Sims, Stan Getz, and, in early 1953, Charlie Parker, for a show that, fortunately for us, was recorded. Parker was flying by the seat of his pants here; he didn‘t really know the arrangements or even some of the tunes, but he still did a marvelous job of negotiating key changes and modulations. We'll hear him with the orchestra doing a tune named in honor of Conover, "Willis."

This edition of Night Lights closes with concert recordings made during Parker‘s guest stint with the Stan Kenton orchestra in early 1954, about a year before Parker‘s death at the age of 34. Parker played a number of shows with Kenton; it was the first time in years that he became familiar with a big band‘s book, and some arrangements were even written for him by Bill Holman. We end with "Cherokee," appropriately enough, since that‘s the tune on which Parker made his revolutionary breakthrough, preceded by the ballad "My Funny Valentine."