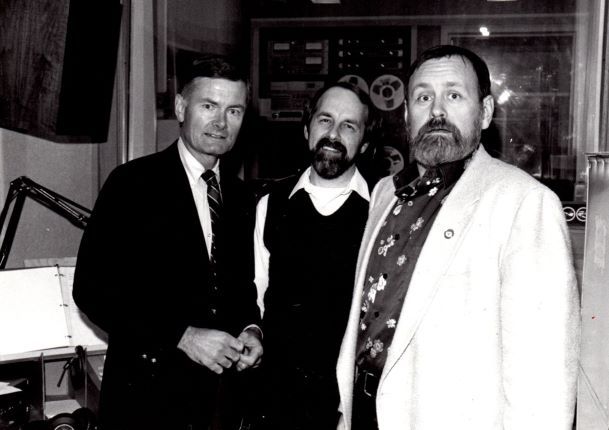

Michael Bourne at right in 1984 with fellow WFIU jazz host Dick Bishop (left) and successor Joe Bourne (center, and no relation, as they constantly had to inform people who assumed they were brothers)

Michael Bourne, a larger-than-life radio personality and jazz journalist who passed away last Sunday at the age of 75, has been justly celebrated this week for his on-air work and adventures as a DJ at WBGO, the Newark, New Jersey-based jazz station that built a global audience over the course of Bourne's 1984-late 2010s tenure. There's a significant prior chapter to the Michael Bourne story, though, that took place in Bloomington, Indiana from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s, when Bourne helmed a primarily-jazz but widely-ranging weekday afternoon program on WFIU, the city's NPR member station.

That slot, dubbed There by its spirited host, developed a strong following and embodied the lingering countercultural zeitgeist of the 70s, nourishing its listeners on everything from classic jazz and Brazilian music to local artists and Frank Zappa. It became Just You And Me after Bourne departed for New York City, handing the jazz chair to Joe Bourne, whom some listeners wrongly assumed was Michael's sibling. (Bourne once told me that he was standing in line at a bank shortly before moving away and overheard two customers in front of him discussing his imminent leave-taking. "Did you hear that WFIU finally got rid of Michael Bourne?" one said. The other replied with disgust, "Yeah, but they're replacing him with his brother.") For the past few years I've had the great fortune to do the show, knowing that giants have gone before me.

On today's program we paid tribute to Michael Bourne with extensive testimony from trumpeter and jazz promoter David Miller, who knew and spent time with Bourne during the DJ's entire WFIU run, as well as Jim Manion, a longtime programming director at Bloomington's community radio station WFHB, who worked as an engineer for Bourne from 1979-80 and listened to him frequently. They both speak extensively to the ways in which Michael helped spark and sustain the vibrant and diverse Bloomington music scene of the 1970s. (We even get to hear Michael as a performer, singing raucously at the Bluebird in 1976 with performance-art band the Brain Sisters.) And Michael himself is heard at length, talking with WFIU Afterglow host Dick Bishop in 2000 about his time at WFIU, his experiences after leaving, and some of his encounters with notable figures in the jazz world. (Not to mention the advice he gave film director Robert Altman on the movie set of Kansas City!)

The program concludes with an invocation of Bourne's daily signoff "Anon, anon" and a testimonial from jazz writer Mark Stryker, who grew up listening to Bourne on WFIU in the 1970s. Stryker went on to become an arts journalist for the Detroit Free Press and to publish the critically-acclaimed Jazz From Detroit in 2019:

I was heartbroken to learn of the passing of broadcaster and journalist Michael Bourne, who died Sunday at age 75.

Michael is best known nationally for his decades as a signature voice of WBGO-FM in Newark, the jazz station for metro New York, where he was on the air from 1984 until just recently. But for a dozen years before that he was a fixture on WFIU-FM in Bloomington, where I grew up. He was one of the most important figures in my early jazz education. Every afternoon his daily program, "There," opened new horizons for me. He introduced me to more music, from staples of the jazz canon to au courant releases, than I could ever recount. He had impeccable taste and a distinctive vocal cadence. When I did some volunteer jazz radio programming in Champaign, Illinois, in 1985-87, I tried to imitate Michael’s pacing and copied some of his favorite phrases -- "And upfront, on the tenor saxophone, Dexter Gordon." I still have the tapes -- they're amusing.

More importantly, Michael was my first true mentor as a writer. I was in an accelerated English class as a sophomore at Bloomington High School North. For our big project in the spring, our teacher paired us up with experts or professionals in the community. I was already interested in writing about jazz, so I got matched with Michael.

I would go over to his tiny one-room apartment, and he would talk to me about criticism, writing profiles, his radio work, his work for Downbeat, the importance of reading widely. I can't tell you how significant all of this was to me. There are still ways that I think about criticism that come directly from Michael and that I pass along to students today with my own little spin. Borrowing from Aristotle, Michael said a critic should always ask three questions: What is an artist trying to do? How well is he or she doing it? And was it worth doing in the first place? Michael edited things I wrote. So much red ink and all of it necessary! Just by observing his life up close, I was able to envision what a life for myself might look like in the arts, even if I didn't end up pursuing a career as a jazz saxophonist.

I remember much of those visits to his pad. To prepare for his radio show, he would time everything out with a stopwatch and write out his scripts in longhand. But he wouldn't read them verbatim on the air. He'd use them as guides, speaking off-the-cuff to maintain an air of spontaneity. His written notes ensured that he didn't forget major points or historical details. He told me great stories about his encounters with heroes like Dizzy Gillespie, Bobby Hutcherson, and others. The one that sticks out most is Dizzy in his boxers in a Chicago hotel room, sitting on the bed, smoking a joint, watching some soap opera he was addicted to, and yelling at the TV about how "that woman is a bitch!"

Michael was definitely an eccentric -- a Falstaffian presence who knew his Shakespeare literally -- he had studied acting in college and earned a Ph.D in theater at IU. He grew up loving opera, especially Wagner, but he also collected comic books as a kid. In fact, he had torn all the covers off his childhood comics and plastered them over every square inch of the ceiling of his apartment. Quite the interior design choice. I remember thinking, "Wow, you mean you're allowed to do that as an adult?" A great lesson to learn at age 15.

I asked him once why he liked jazz. Besides telling me the music that got him interested in the idiom in the first place – Dave Brubeck's "Strange Meadowlark" and Art Blakey's "Bu's Delight" — he had an interesting perspective and unique way of expressing it. He said he liked jazz best because about 70 or 80 out of every 100 jazz records released were worth hearing, while only 40 or 50 of every 100 classical records released were worth hearing, and 15 or 20 pop records out of every 100 were worth hearing. Whether you agree or not with the sentiment, what a clever and creative way to make the point!

Through the years, whenever I met folks from WBGO, I would always ask them to give Michael my regards. I only spoke with him once since I was a kid. This was in fall 2019, when I was at WBGO doing an interview about my newly published book, "Jazz from Detroit." A station official called him for me and handed me the phone, and I was able to express my appreciation. What a gift! I was also able to inscribe a copy of my book for Michael and place it in hands that made sure he got it.

The bumper music on his afternoon program in Bloomington, bridging his show and the start of "All Things Considered" was Joe Farrell's recording of "Follow Your Heart" -- a great song written by John McLaughlin. Follow your heart: That's certainly what Michael did with his life.

(Mark Stryker is a Detroit-based arts journalist, critic, and author of Jazz from Detroit. [University of Michigan Press], A 2020 inductee into the Michigan Journalist Hall of Fame, he was an arts reporter and critic at the Detroit Free Press from 1995-2016. He is currently coproducing a documentary film inspired by Jazz from Detroit. Stryker was born in Bloomington, Ind., and earned a master’s degree in journalism from Indiana University.)