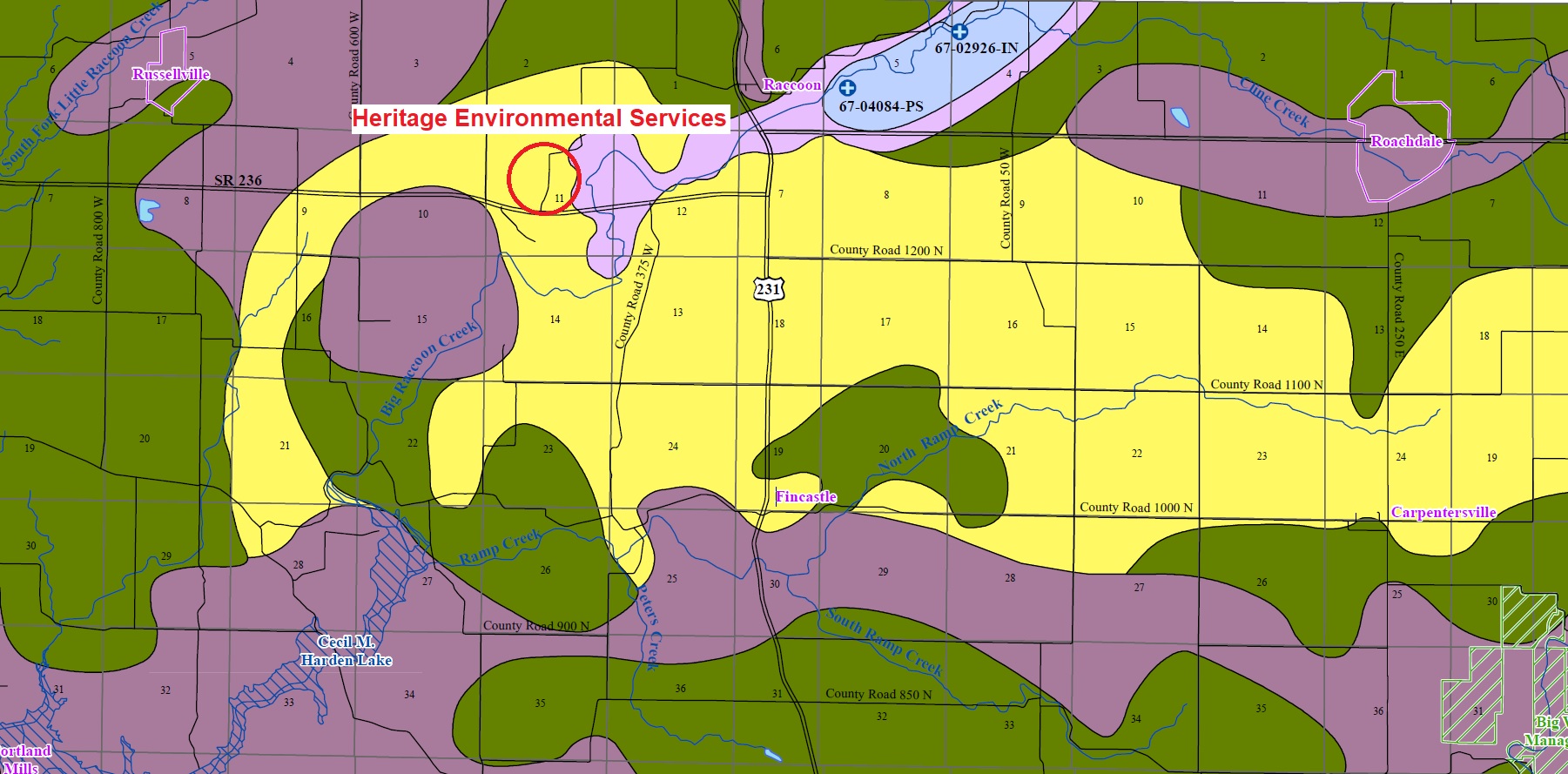

Before contaminated soil arrived from East Palestine, Ohio, many Putnam County residents were unaware of the nearby hazardous waste landfill. (Courtesy of Jason Spurlock)

Putnam County residents learned last month that toxic waste from East Palestine, Ohio, had been delivered to a nearby landfill. For some locals, that revelation has led to a deeper search for answers about the Heritage Environmental Landfill’s 40-year history.

Kathryne Williams lives near the Heritage landfill. After a charged meeting last month between locals and Heritage Environmental, Williams said she was overwhelmed by conflicting information.

“A friend of mine, Morgan Meyers, sent me the meeting. And it was probably 11 o'clock that night, and I stayed up all night watching it,” Williams said. “Honestly, it was it was very concerning.”

Residents showed up at the Russellville Community Center that night to express their objections to the incoming waste, only to discover that three truckloads had been dumped earlier that day.

Read more: Holcomb opposes East Palestine waste coming to Indiana landfill

Williams grew up in a subdivision named Heritage Lake. She’d seen trucks drive by with the Heritage Environmental logo and its name on the uniforms of sporting teams. But until recently, she had no idea what it actually was.

“Even though I had lived there for so long, I was not even aware of Heritage Environmental Service’s existence, or that it was a hazardous landfill,” she said. “When you hear the name Heritage Environmental Services, the last thing you put that towards is a landfill.”

Unanswered questions

Williams was alerted of the Mar. 1 meeting by her friend, Morgan Meyers. Like Williams, Meyers is new to environmental issues. As a former Marine, she was exposed to environmental toxins. She suspects it may have caused her to develop breast cancer. Meyers is worried that her children could face the same danger.

“That next morning, I showed up at (Kathryne’s) door with posters and paint,” Meyers said. “Then she got out her kids’ crayon box, and we just went to town making signs, and we went out to protest.”

Both women say they’re new to activism but were motivated to get involved because of their concerns and their search for answers.

“This is the first time I've really gone about being so public about a strong view of any kind, but I do find that this is something that affects everyone,” Williams said.

“My usual day was feeding the chickens going and slopping the hog and just taking care of my farm animals in my garden,” Meyers said. “Now it has completely turned into finding out more about the situation and advocating for our community.”

Williams and Meyers acknowledge that toxic waste facilities are essential and that Heritage Environmental has largely complied with regulations. What worries them is the site’s location.

The landfill sits beside Big Raccoon Creek, which feeds into the Cecil Harden reservoir. But they’re even more concerned about what lies underneath.

“Heritage environmental services actually sits on top of the Tipton Till Aquifer, which is an unconsolidated aquifer,” Williams said. “That means it's not protected by thick layers of clay or limestone.”

Nearby towns draw their drinking water from the reservoir. Landfills like Heritage are required to take measures to ensure that toxic runoff called leachate doesn’t permeate underground water sources.

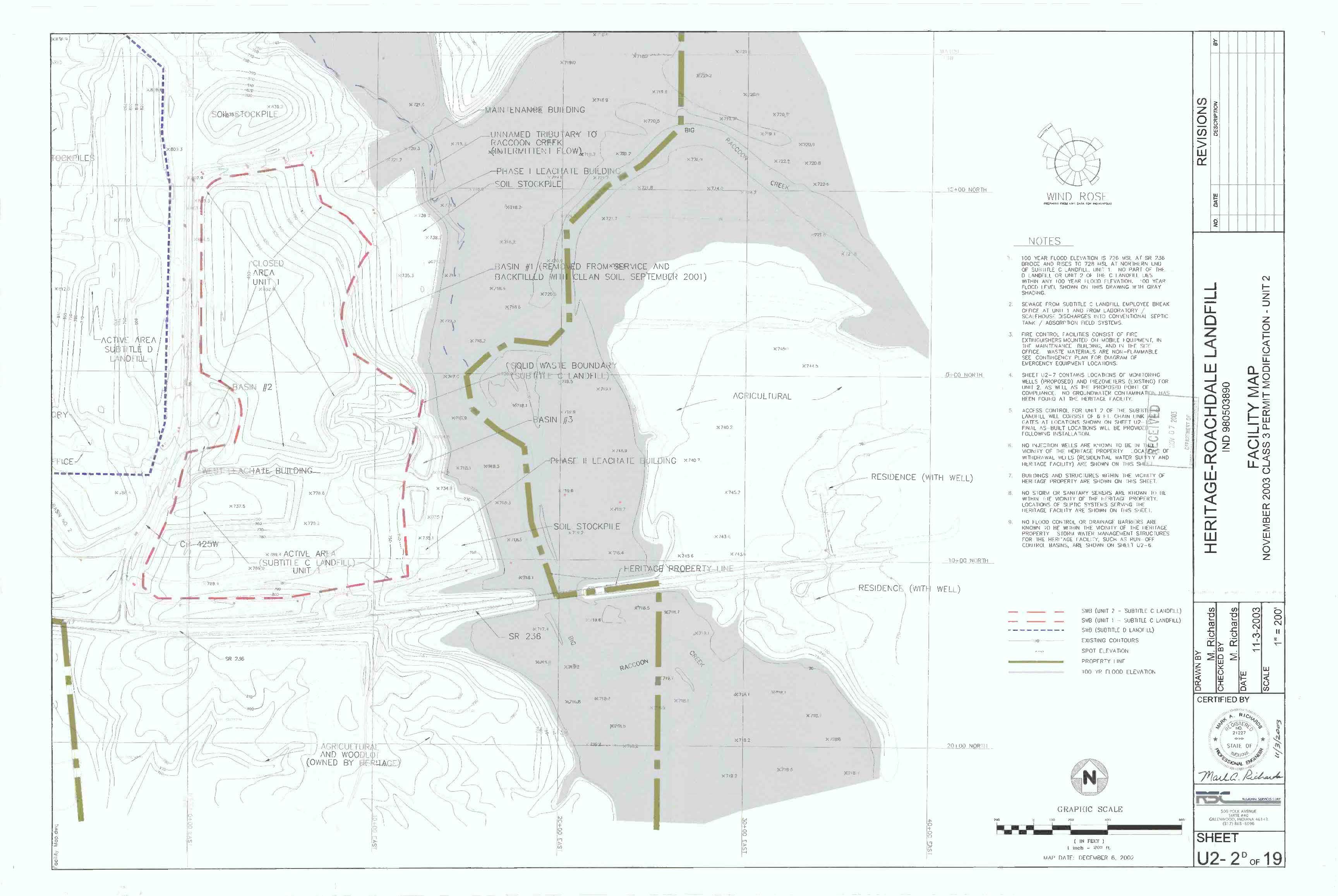

The Roachdale site is divided into three units, including two Subtitle C sites which are approved for hazardous solid waste. The newer Subtitle C unit has a double PVC liner that prevents leaks, but the first one opened in 1981, before the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). That means for more than 40 years, toxic waste has been sitting underground without a liner.

Former EPA superfund director William Muno says that can be a risk, but Heritage should have measures in place to detect leaks.

“That’s a legitimate concern,” Muno said. “The old cells that are unlined do have the potential of having leachate migrate out of those cells.”

Heritage Environmental has a network of wells that monitor groundwater around its site for leachate. Muno said that if the pre-RCRA cell leaked or one of the PVC liners broke, it should be detected by that network.

The heritage of a landfill

Seventh generation Putnam County resident Lora Scott is worried about the long term safety of the landfill.

“Clay is a good material. It is pretty highly impermeable, but when you are looking at a resting site for that waste, that will be there for centuries,” she said.

Scott serves on the county Board of Zoning Appeals. Her experience with local government and historical research has been an asset to the other activists.

Part of what Scott wanted to uncover was how the landfill was approved for construction over the Tipton Till Aquifer in 1980.

“How were the people in the county involved?” Scott asked. “Did they welcome the hazardous waste landfill, or did they take any actions to keep the landfill from locating here?”

Back then, Scott was a young parent. She said that although she was aware of the landfill opening, she didn’t have time to get involved. Four decades later, she learned the full story.

The landfill was opened by Heritage Environmental’s precursor, Indiana Liquid Waste Disposal (ILWD). The company operated a plant in Columbus, Ind. but was forced to close after the Bartholomew County zoning board and board of health filed a lawsuit over waste disposal problems.

“Putnam County did not adopt zoning until 1992, and that opened the door for ILWD to decide to come here,” Scott said.

“The local people presented petitions, they presented their own engineering studies of the area that ILWD had bought,” she explained.

The Putnam County Board of Commissioners attempted to pass an ordinance to prohibit the construction of landfills, but they were sued by ILWD in the Owen Circuit Court.

Three years after the ILWD landfill in Roachdale began accepting waste, RCRA passed into law, requiring double liners around hazardous waste landfills within a quarter mile of an underground drinking source, like an aquifer.

In 1986, ILWD became Heritage Environmental.

Seeking reassurance

Executive Vice President of Heritage Environmental Ali Alavi issued a statement to Indiana Public Media that “there are several layers of protection in place associated with the operation of the Putnam County facility.” He listed the following:

- Compliance with stringent federal and state regulations governing the design, construction, and operation of such facilities;

- Rigorous permit application process;

- Compliance with strict permit requirements;

- Oversight and regular inspections by the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Indiana Department of Environmental Management;

- Employment of operating practices that are protective of human health and the environment;

- Use of a synthetic double liner system (on units built since 1984) and cap to mitigate infiltration and control and capture of any leachate generated; and

- Monitoring of a network of groundwater wells in the vicinity of the landfill.

Alavi said, “these elements have contributed to a 40+ year record of operating the facility in a manner that is protective of human health and the environment.”

In the past decade, the Roachdale landfill has received one infraction from IDEM, for a bag of hazardous waste that caught fire during unloading in 2019.

Muno thinks that one bag of burning waste isn’t a metaphorical garbage fire.

“If you would look at the RCRA regulations, they are extremely complicated and large in number,” he said. “One violation four years ago shouldn't be cause for concern.”

Heritage Environmental is required to test its groundwater daily. If contaminants escaped, the company would have to report them immediately to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

Scott, Meyers and Williams are worried the company and county services don’t test for every possible contaminant. Muno said that to identify a leak, they wouldn’t need to. There are chemicals — such as trichloroethylene — in water that can serve as indicators of other toxic compounds.

Read more: Franklin advocates have mixed feelings about new cancer cluster guidelines

“You don't have to analyze for 1,000 chemicals to know that either inorganics or organics are migrating out of the landfill,” Muno explained.

Nonetheless, when it comes to safety, Putnam County residents have more questions than answers.

Scott wants to know the location of Heritage Environmental’s monitoring wells to determine whether the whole perimeter is covered. Williams isn’t sure how long the liners under the landfill will survive. And Meyers wonders whether nearby towns should construct new wells in case of possible leaks.

Muno said there are no absolutes when it comes to safety, but sites like the Roachdale landfill need to have redundant safety measures in order to maintain their permit.

“The whole concept of the Superfund cleanup is to send waste to facilities that don't become future Superfund sites,” he said.

Groundwater testing results for the Heritage Environmental facility can be viewed here.

An analysis conducted of the Bainbridge well is available on the IDEM website.