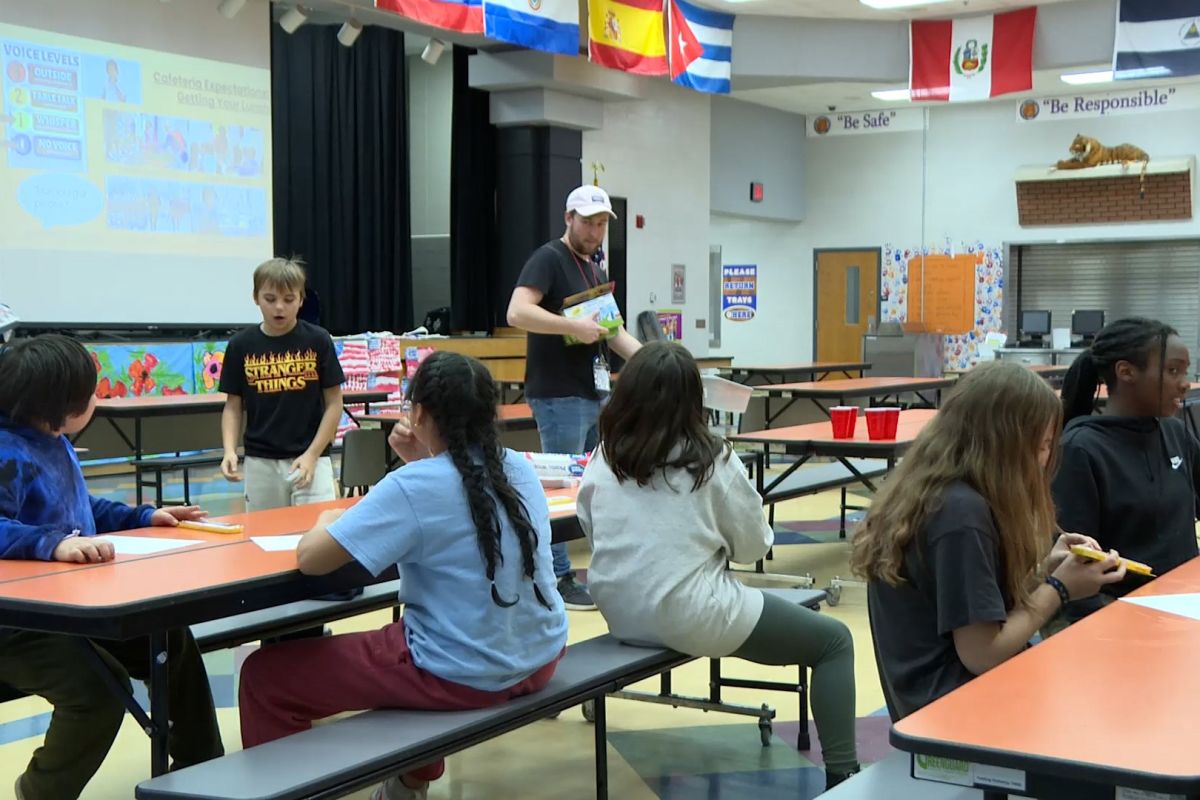

Kids at Templeton Elementary School collect supplies to start a painting activity. (Isabella Vesperini)

Children run to the tables in the cafeteria at Templeton Elementary School for their after-school snack: yogurt and crackers. Their giggles fill the room.

One child spills yogurt on the table and asks the volunteers to help clean up. There are three volunteers and about 20 children – creating an exceedingly small ratio of kids to adults.

Lately, it has been hard to find a program like Templeton’s. Affordable and accessible after-school childcare programs in the U.S. are increasingly hard to come by. Indiana’s programs are no exception to this growing trend.

At the back of the classroom, a boy fills up red solo cups with water. He places two at each table as the volunteers pass out mini paint palettes and white sheets of paper. The kids spin the palettes on the table, mesmerized by the rainbow of colors.

Even after school, they are learning. Every brush stroke, game of tag and snack fuels their creative muscles, expands minds and grows bodies. Experts say this kind of learning, the kind you can only garner from play, is essential for childhood development.

Parents will pick them up by 5:30 p.m., after a full day of work. Some of them will be back in just a few hours, at 7 a.m. for the morning program. Without Templeton’s program, it’s not clear what these families would do. For thousands of Indiana families, this uncertainty is a daily reality.

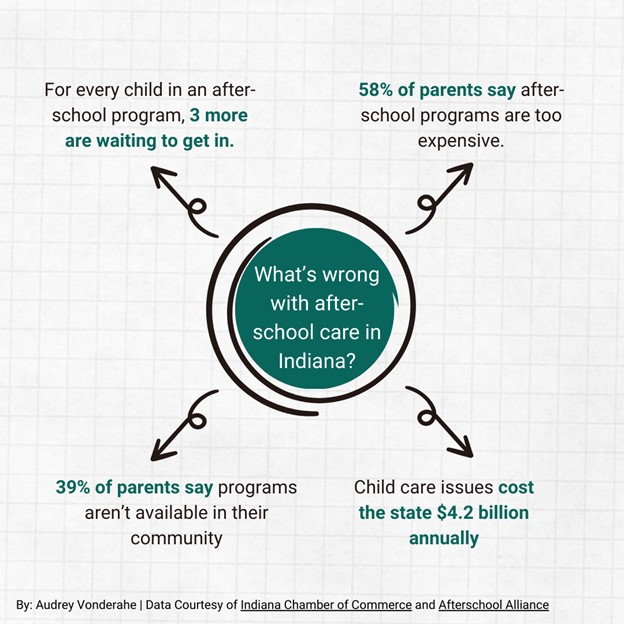

For every child in an after-school program in Indiana, three more children are waiting to get in. Fifty-seven percent of parents of young children missed work or class at least once in the past three months for child-care-related reasons. Statewide, only 61 percent of children needing childcare can be served through existing capacity.

Since 2014, programs have become increasingly expensive. On average, parents pay $75 a week per child. According to a survey done by the Indiana Chamber of Commerce and Early Learning Indiana, families spend an average of $677 a month on programs, coming out of their personal budget 66 percent of the time.

Across the 14 Monroe County Community School Corp. (MCCSC) elementary schools, 462 students attend morning programs, and 351 attend their after-school programs, according to Director of Early Learning and Enrollment for MCCSC, Tim Dowling. The programs try to reach as many students as possible.

Read more: Bus driver shortages are spilling over to some after-school programs, limiting their reach

Dowling said these programs allow kids to get more support and also makes parents’ lives easier. He knows this from personal experience, too.

“When my children were younger, it allowed my wife and I a lot of flexibility in our work schedules,” he said. “We know that families’ various needs, so it helps families whether it's a morning program an afternoon program.”

The 21st Century Community Learning Centers Grant, a federally funded program, allows seven of MCCSC's 14 elementary schools to enlist as Title I schools, which primarily serve low-income families.

Arlington, Fairview, Templeton, Grandview, Highland, Summit and Clear Creek Elementary schools receive grant funding. From the seven schools, 52 percent of the morning students attend for free, and 46 percent of the afternoon students attend for free. For families that don’t qualify for support, the morning program costs $7.75 per day for each child.

The afternoon program costs between $7.25 to $8.75 depending on school location since the length of the programs differ slightly due to the tiered bus system. Despite the funding available, these daily totals quickly add up.

MCCSC struggled with staffing their programs during the pandemic, Dowling said. They had to rely on office staff to fill in the gaps. But since then, they’ve started to hire high school and college students.

“With its schedule flexibility, the position is attractive to a lot of college students,” he said.

Dowling said it takes a few weeks at the beginning of the school year to get all families situated as they wait for college students to come back to town.

The average waitlist lands between 10 and 25 families. They were able to take about 10 families per week off the waitlist in August.

Read more: Law now lets parents decide on taking kids out of school for religious ed

MCCSC hasn’t seen any increase in the number of children attending their programs, but the Boys and Girls Club has, said Jade Parrish, program director at the Ferguson Crestmont Club location.

When Parrish started working at the club in March, she’d see 75 to 90 kids daily, the majority of them being in kindergarten through third grade. Now, between 90 and 120 kids show up.

The number of middle school and high school students attending has also grown. In 2023, between 15 to 20 middle school and high school students attended. This year, Parrish has seen over 30 attend in one day.

“A big reason that there is such an increase in the number of members coming to our clubs throughout the week is [because] it's one of the only affordable options for kiddos after school,” she said. “Our members only have to pay a $20 membership fee for the year. And in comparison to different childcare options, that's very affordable.”

The full yearly cost to send a child to the Boys and Girl’s club is $750, Parrish said. Families pay $20, and the rest is covered by community, state and federal grants. The average cost per month for childcare in Bloomington is $820, compared to $800 per month for programs in Indianapolis.

The Ferguson Crestmont club serves kids from Arlington, Fairview, Marlin, Tri-North and Bloomington High School North. For those families, the average income per year is $7,300, well below the national household median income of $74,580 in 2024 and the median household income in Monroe County, $51,945. Almost all of those families rely on food stamps and are single-family households.

During club hours of 2:45-7 p.m., Parrish said, kids have a recess hour and do work that focuses on art, leadership, character and healthy lifestyles. They also have snack time.

“In the low-income area of Bloomington, it's more than a snack,” she said. “It's a nutritious meal."

Parrish said the Boys & Girls Club also has special programs, like Club Riders, where kids can learn how to ride a bike. They also teach students how to ride a skateboard and write poetry.

Parrish has seen kids at the club grow academically. Students who have participated in their tutoring program have raised their math scores 87 percent and reading scores 57 percent.

“A lot of kids will come after school be matched with a consistent tutor,” she said. “That's just one more adult that they have a relationship [with] that they build.”

---

Lakshmi Hasanadka, chief executive officer of the Indiana After-school Network, said the childcare field is “disjointed”; after-school programs are not required to register with the state.

If they do, they report loosely to a few different agencies, including the Indiana Department of Education and the Indiana Office of Early Childhood. This creates uncertainty about the number of programs that exist in the state and raises questions about their quality. It’s unclear how many programs exist in the state. Hasanadka estimates there are about 4,000 of them, but even that number doesn’t include every program.

The lack of data also makes it harder to get funding because there is little evidence to prove programs are having a hard time. There is also no central resource to look for available care, or any reviews about a program’s legitimacy. This makes it harder for parents to find and entrust their childcare in community programs, Hasanadka said.

In turn, according to Hasanadka, the uncertainty further widens the opportunity gap between children in families with different socioeconomic statuses. Well-connected families who can afford private care have an advantage.

"The families who have a lot of resources, they will figure it out, but the families who don't have very many resources, it's a lot harder for them,” Hasanadka said.

Low funding also makes it harder to run high-quality programs, Hasanadka said. Programs that are better quality are significantly more unaffordable for families. According to the After School Alliance, 58 percent of parents say after-school programs are too expensive.

Hasanadka said good programs will incorporate project-based learning, such as artwork or STEM lessons, like MCCSC does. But many places don’t have the resources or funding to support these initiatives, leading to an early learning gap that persists.

“The goal of some programs is to keep the kids safe until their parents can pick them up after work, and that's fine,” she said. “There's a place for that; families need that. They need to know that their kids are safe and having fun and happy, and that's OK.”

While it is challenging to support consistent after-school programming, Hasanadka said the routine is good for kids’ development.

Recently, more funding has become available. The 21st Century Community Learning Center, a federally funded program, supported after-school programs for families with low incomes. On My Way Pre-K distributes grants to 4-year-olds from eligible families to attend a quality pre-K program the year before they begin kindergarten. The Early Head Start program is a federal program that focuses on low-income families, enhancing cognitive, social and emotional development for kids under 5.

However, a lack of data transparency, discrepancies in program quality and expense continue to make it difficult for parents to ensure their children are kept safe while they work to support their families.