In August of 1816, a letter started its journey in the Vevay, Indiana, post office.

It would travel all the way to Grand Quevy in what was then the Netherlands. French exile Marie Barbe François Lakanal, who along with her husband Joseph had recently settled across the Ohio River from Vevay near Ghent, Kentucky, had written to her nephews and exhorted them to make the journey across the Atlantic. Her sixteen-page letter contains very detailed instructions for the two young men and their families, as well as a listing of items Marie wished for them to bring her from Europe.

The Lakanals’ experience along the river was not typical—they were clearly wealthy and lived on prime real estate in Gallatin County—but Marie’s letter offers a glimpse of the pioneer experience along the Ohio River in Indiana’s statehood era.

Marie promised her nephews that she and her husband would give them forty acres of land to cultivate for five or six years—enough time, she figured, for them to raise animals, learn to farm, and learn English. When they had enough money, her husband would obtain one or two 540-acre lots from Congress for the men; they would then have five good years to pay for the farms. They would have hunting rights in twenty leagues of forest, and would find deer, hare, rabbit, partridge, and wild duck, as well as fishing in “an immense river.”

Marie advised her nephews to convince their parents and siblings to make the journey, too, for farm work would require many hands. She also counseled them to contract for four indentured servants—two men and two women—for a term of six years: “I strongly advise you to choose people about whom you feel sure, and who are used to pulling a cart or else harvesting on farms.”

Fall was the best time to make the trip, according to Marie. The weather would be favorable, and that way, the newly arrived wayfarers could begin farming the land as soon as possible in the spring. Marie warned the men not to divulge that they were coming to America to settle lest they encounter problems at the port (“the government does not like to think that any country is better than theirs and always looks with a bad eye on emigration”); rather, they should state they were traveling on family business.

The voyage from a Dutch port to Philadelphia or Baltimore would last from twenty-five to thirty-five days, and they should prepare their own meals. Marie warned the men that cooking aboard ship was men’s work, not women’s.

Once they reached the U.S., Marie informed them that they should buy a horse to carry their baggage, because their journey to the Ohio River in either Pittsburgh or Wheeling would be on foot. Regarding American cuisine, Marie wrote: “I warn you that you will never see a drop of soup, nor beer. There is tea and dark water that is called coffee, although it does not contain one grain of it. You will find brandy and very good cider.” Marie advised the men not to be fearful: “You need not be afraid of sleeping in isolated inns, you can sleep everywhere with the greatest of safety. Americans are good people. Neither do you need to fear wolves, bears, or thieves along the way, a person alone can travel without apprehension.”

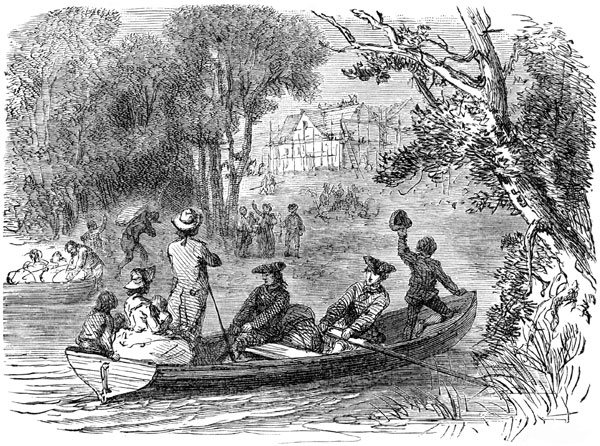

Once they reached the Ohio River, the men would hire a boat for the rest of the journey. They could buy whatever they needed, and the river was “covered with wild duck.” “If you have your gun you can add to your menu,” Marie informed them. She also warned them to go to a coopery for several days in order to learn how to store barrels; they would need to be as self-sufficient as possible.

Marie asked the men to bring many items from Europe: among the necessities were wooden shoes for men and women, because the dew was so heavy near the river; slippers of leather and lace for herself and her daughters; and, seeds and cuttings. Marie desired seeds and cuttings for plums, apricots, pears, peaches, currants, chicory, alfalfa, red cabbage, turnips, leeks, white beans, peas, tarragon, chives, and poplar and willow tree seeds. Finally, her husband Joseph wished to have half a ream of good letter paper, the same amount of lined paper, and a case of eau de cologne from Paris.

How would they find her house? Directions in 1816 were no different than they are now; the men would see it three miles before arriving at Vevay, on the left side of the river; there were two houses there, and the Lakanal family manse was the first one before the creek.

A Moment of Indiana History is a production of WFIU Public Radio in partnership with the Indiana Public Broadcasting Stations. Research support comes from Indiana Magazine of History published by the Indiana University Department of History.

IMH Source article: Phyllis Michaux, “Instructions from the Ohio Valley to French Emigrants,” Indiana Magazine of History 84, no. 2 (June 1988): 161-175.