stef shuster: Part of why we should care what happens to trans people in health care is that it reflects flaws in the system of health care itself.

Alex Chambers: This week on Inner States, a conversation about trans medicine. As our guest stef shuster was saying, understanding trans people’s experience of health care actually offers a pretty good guide for making it better for everyone, especially marginalized people. But also, it matters for trans people! This conversation also gets into how stef shuster started researching the sociology of gender and how doctors’ own relationships with uncertainty shapes how they approach patients who don’t fit their expectations. Coming up, right after this.

Alex Chambers: This is Inner States, from WFIU in Bloomington Indiana. I’m Alex Chambers. So, state legislatures across the country have been passing a lot of legislation that targets people who are gay, or trans, especially young people. Alabama, for example, wins for the strictest anti-trans legislative package in history. It’s called the “Alabama Vulnerable Child Compassion and Protection Act,” and the law makes it a felony for a doctor to perform a surgery or even prescribe medication for a gender transition to anyone under 19. In Texas, governor Greg Abbott announced that gender-affirming treatments for transgender youth “constitute child abuse”. Here in Indiana, the legislature has not - yet - been quite as restrictive. But it did just override a significant veto. Our governor, Eric Holcomb, decided a bill that would keep transgender girls out of girls’ school sports didn’t solve any real problem. So he vetoed it. Holcomb is a Republican, by the way. Then, a week and a half ago, the legislature used a technical session to override that veto. That means, in Indiana, at least for now, transgender girls cannot join sports teams with other girls.

Alex Chambers: With all that in mind, I want to replay a conversation we aired on WFIU last fall, as the last episode of our interview show, Profiles. This is a conversation with sociologist stef shuster. Stef teaches at Michigan State University and they’re the author of a book called Trans Medicine: The Emergence and Practice of Treating Gender. It came out last year. Trans Medicine looks at how health professionals interact with patients who come in looking for gender-affirming care. There’s not a ton of scientific research on medical care for trans folks. Combined with medical providers’ own lack of experience, that undermines their ability to put together good treatment plans and help people make medical decisions related to gender.

Alex Chambers: This week on Inner States, we present stef shuster, in conversation with Stephanie Solomon. Stef talks about their time in Bloomington, how they ended up studying the sociology of gender, and how doctors’ own relationships with uncertainty shapes how they interact with trans patients. Guest interviewer Stephanie Solomon is the Youth Program Coordinator at the Indiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence, and was once stef shuster’s neighbor in their undergraduate dorm at IU. And so, without further ado, here is sociologist stef shuster, in conversation with Stephanie Solomon.

Stephanie Solomon

Stef and I go way back, meeting here in WFIU’s home Bloomington at IU as freshmen in the year 2000. Actually in neighboring dorm rooms. So welcome back to Bloomington Stef.

stef shuster

Feels good to be back

Stephanie Solomon

So I would love to hear about a formative experience in Bloomington that kind of shaped and brought you where you are today.

Umm yeah, there's so many there are so many formative experiences right in college. So I grew up in Louisville, Ky and moving to Bloomington, IN, it was the first—it was the 1st place that I moved away from, you know where I grew up and I was already out as a queer person at the time. Caught off guard by was how there seemed to be a really thriving queer community in Bloomington and that was something that I was not expecting. So you know, I think that finding community and really having room to understand my identities, both as a person, but also going through so I was a sociology major and falling in love with the topic and the methods and within that I was taking, you know, sociology of gender and sexuality and social movements and medicine, and really I just fell into this area that has become my career, so it's hard to pinpoint like one formative experience. But there are so many, it's yeah, it's kind of incredible to think about.

Stephanie Solomon

So I'd love to hear who your mentors were both when you were an undergrad and what led you down that road to sociology specifically.

stef shuster

Yeah, so I I certainly was not, you know, I think a lot about now, the students that I work with now feel so much pressured to the minute they step on a campus, you know to declare their major. I had a much more meandering path. I started as a—I think it was a double major in photography and English. Then I moved to human development, family studies. I thought I was going to be a counselor for queer youth. There were some troubling aspects of the way that the curriculum was taught at the time.

And I really found myself leaning more towards sociology because it gave me a language to understand the social problems that I was seeing in you know, our everyday lives and also like from a broader national perspective.

You know when I when I came to college, I didn't—I didn't necessarily want to be in college, it was—I was not the best student in high school so.

Stephanie Solomon

We had that in common.

stef shuster

So when I got to college I it, it felt like it opened up my brain, you know? And I loved going to classes and I loved learning, and in sociology there was just something that really resonated with me and I think it was partly giving me a language to understand social patterns and why people are the way they are and what helps explain why it is that we do what we do.

So my mentors at the time, professors Elizabeth Armstrong and Melissa Wild really encouraged me to go out and start collecting data and learning how to do sociology. So not just like reading about it, but actually doing it. I know this might sound funny to some people, but it was actually the methods that, that I, that's what I fell in love with the, you know, going out and interviewing people and observing people that you know that sounds a little weird but um -

And also playing in archives, all of it and then what to do with the data and how to tell stories from the data it just, I couldn't get enough of it. And I had actually a graduate student who sat me down in a coffeehouse here in Bloomington. I remember the day so clearly and he was like you have to go to grad school and I was like, Oh no, you know like, I didn't even know if I wanted to go to college and grad school is a huge commitment. There's no way I'm doing that. And his name was Albert Almasan (?) and he was like no, you have to go to grad school and he was really trying to encourage me. And I was like no, no, no, no, no. But he planted that seed in my brain. I went off for a couple of years. I strangely got jobs collecting data for social science research organizations. And eventually got to a place where I wanted to work on my own research. I was starting to read a lot in Trans Studies at the time. And just found a lot of what was coming out, especially in sociology in the early 2000s, to be full of misconceptions about transgender people and really told from all of these kind of like shaming, right? Like trans people should live lives full of shame. And it's, it's something that is stigmatizing and bad, like trans equals bad. And that compelled me to go to grad school.

Stephanie Solomon

So after Bloomington, you moved to Iowa to attend Graduate School, you took that advice.

What was that like to move to a new place?

stef shuster

Yeah, I mean it was scary, you know, it was, it was scary because at that time I had established such deep connections to Bloomington and I just, you know, I had a really strong community here and Bloomington was a place where I felt like I could be, I could be myself, I could be out, I could be nerdy, I could be excited about books and gardening—thanks to you—and you know there's so much in this area that is satisfying. Like for quality of life for me.

And all I knew about Iowa really was that it has corn? And I don't know if you remember that night when I when I accepted the offer to attend my PhD program in Iowa. But I was like pacing and pacing and pacing outside of the mailbox I think on maybe 4th St somewhere and I finally just had to like open the door and toss it in and it was like. That's it, like it's done.

Moving to Iowa was hard because I didn't know anyone. I didn't know a single person I didn't know much about the state. I didn't have the politics of the state. And also by that time I had started identifying as trans, and had started thinking a little bit about gender affirming interventions for myself and finding a health care provider. Anyways, I think for a lot of people it's really hard. You know, like I think most people want to find providers who listen to them who will see them as human and really listen to their concerns. And adding on top of that is a little bit of a layer of complexity given like the gender part of my health care needs, so.

Stephanie Solomon

I think really this is when we get to your book. When we start talking about health care. To give us the main premise of Trans Medicine.

stef shuster

Yeah, so let's see. So again when I moved to Iowa City, I knew that I wanted to work in the sociology of gender and medicine. Those were things that I had developed as interests when I was here at Indiana. But I didn't quite know how to make that happen, and I knew that I had at least five, maybe seven years, to figure it out. So I started, I started slowly when I moved to Iowa City I was like I first need to establish a community. And so I think this happens a lot. Like you know, you move to a new place. You need to figure out where the coffee shop is and the grocery store is and where to live and how to get to work and for me I started asking around like where are the health care providers who who know how to work with trans people or who want to work with trans people. And so many people like in the transgender community. And also, you know, like my peers in my program, were just like I have no idea

And so I started doing a lot of health care work like health care, advocacy work and working with a handful of providers who were eager to be better doctors who wanted to work with trans people and felt completely ill equipped to do so. And so we would, you know, we would host workshops and events and have these really intense conversations. And that work actually opened a window for me into understanding the kinds of challenges that providers feel in working with trans people.

And sociologically, that actually is quite interesting, right? So I guess like to answer your question, I have to go back a little bit, like, you know, into how the book started before I can answer what is this book about,

From a sociological perspective, when we think about medical providers, medical providers are professionals, right, and what that means is that they have expert knowledge and experience. So as people who—you know, if we're patients, when we go to the doctor, we expect that they know what they're doing. And sociologically, when doctors are like, I have no clue what I'm doing, it presents a puzzle, right? And for me, the puzzle was what shapes that feeling of uncertainty. And I really sat with that question. And then and then all of a sudden I was like, oh I have to work on a dissertation. [laughter]

So I, I started interviewing providers and because I wanted to know if that was something unique to Iowa City or if that was representative of a national uncertainty. And so I just started picking up the phone and calling providers and reaching out to my networks. And the more that I spoke with providers, the more that I understood that part of this story of grappling with how providers fare in trans medicine is really a story of uncertainty.

And so the book that just came out, Trans Medicine is—it's broken up into two parts. So part one, I look at the historical context that shaped trans medicine. A lot of that work comes right out of, you, know, the Kinsey Institute here. So that was fun to like, be able to come back to Indiana and work in the Kinsey Institute and the resource specialists, there are amazing and helped me find so many documents and a lot of those were from this guy named Harry Benjamin.

Stephanie Solomon

He was an interesting character in the book.

stef shuster

He certainly was. Yeah. You know, he was nationally known as like the medical provider in the 1950s and 60s. And so at the Kinsey Institute, they have a Harry Benjamin collection. He was meticulous in his record keeping, so you can actually track all these letters of correspondence between providers to Benjamin and from Benjamin back and patients. And those letters helped me understand like where trans medicine really took off, like as a field, and the assumptions that shaped.

How doctors think about trans people and so for me, I'm not a historian, but the way that I approach the history is more from like what are the patterns that help us understand the contexts and also how do those contexts help us understand what's happening right now?

So Part 2 of the book is all of the interviews I did with providers I also went to healthcare conferences and observed them. Which is fascinating, like it was a great data source. But the questions that motivate the book really are about, How do they manage their uncertainty? How does the fact of such vast uncertainty also challenge their sense of themselves as experts? And what does trans medicine teach us about medicine in general?

Stephanie Solomon

Mm, that idea of expertise is one that I hope we can keep coming back to. What kept coming up for me as I was reading was who is the real expert? Is it the person living in their body or is it the person who's been medically trained? So I'm glad you brought, that up, and I want to continue threading that through.

[music]

Stephanie Solomon

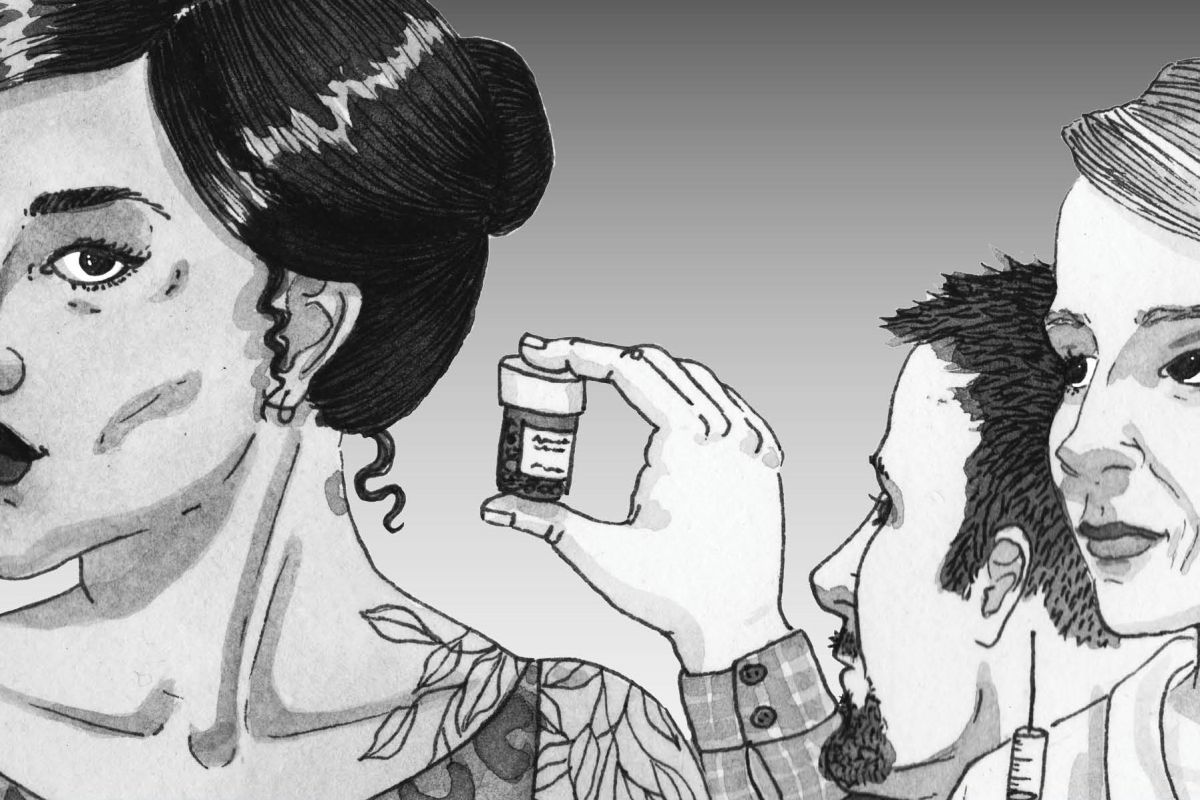

I'm Stephanie Solomon. For those of you just joining us, I'm speaking with Stef shuster, the author of Trans Medicine: The Emergence and Practice of Treating Gender. Stef shuster is an assistant professor of sociology at Michigan State University. So I can't talk about the book without bringing up the beautiful cover of the book. You keep looping through Bloomington and we're in Bloomington right now, and one of our very close friends from Bloomington drew that for you. How was that working with an old friend and artist?

stef shuster

Yeah, so I think the cover is amazing. Ileana Haberman did a great job and you know it's one of those things as as an author of a book I knew that I had to make some decisions about the cover, but I was so invested in like must meet the deadline must meet the deadline. And when I finally caught a moment to catch my breath a little bit, I was like, I really want the cover to reflect the main themes that run throughout and to be a deliberate representation of both the history and what's happening right now in trans medicine.

And I didn't know how to do that with, you know, someone that probably does an amazing job, you know, like at NYU press they have like so many great people there. But I really felt compelled to work with someone who knew me and I mean that cover, it is powerful and it's eye catching. And yeah Ileana did a great job and I certainly gave her a lot of ideas that were looking back now terrible ideas. But I think that she really was an open listener and reflected all of the wonky ideas that I had in crafting that image.

Stephanie Solomon

Well, I think it is a great representation of the content and so I love that fusion, fusion of creativity and brilliance that happened there. So I've been out of academia for a very long time, I graduated with you in 2004 and just returned to IU to study public health this past year. And one thing that I really appreciated about your book was I felt a little intimidated going into and knowing you and knowing that you've been in academia, and I often feel kind of blown away when we're when we're talking about your work. But I found the book to be really accessible. So I'd love to hear about who your intended audience is for the book, and if that was an intentional thing that you did by making it a really accessible read.

stef shuster

Yeah, thank you for that's like high compliment. You know going into the beginning of the writing process, I was mostly thinking about an academic audience. I'm an assistant professor, which means that the next major hurdle to get promoted is I have to, you know, have publications and do all these things. And so when I went into it, I was thinking mostly about how to get myself to the associate professor position and, and the book helps me achieve that. So, and like you know, I was writing the majority of the book during the pandemic, and I'm not sure if this resonates with you, know you and also listeners, but some of my priorities changed a little bit and I had a lot of time to think and reflect on what I wanted the project to be and who I wanted it to reach.

And so somewhere right around the middle I was like, I actually think that there there's enough, there's enough here about you know the experiences of medical providers and how they continue to, for example, punish people who don't uphold, you know norms, that that probably resonates with a lot of people and from a lot of different marginalized groups. And so I started kind of trying to imagine if my brother picked up the book. My brother helps me with my website, so like there's there's there have been moments where he's like it sounds like you're doing really cool work, but I have no idea what you're talking about and that like that. But that started bothering me and so I started imagining that I was writing to him and I wanted him to be able to pick up the book and understand it, and so I think in that way it really helped me to reframe to like, remove as much jargon as possible, but to keep the story which has so many different moving parts in it.

And I also imagine like those providers that I met in Iowa City who were like we want to work with trans people, but we have no idea what we're doing. This book is not a how-to, right? It's not a—it's not how to administer hormones. It's more like how to be a more mindful doctor.

Stephanie Solomon

Yeah, and I I think about what it must have felt like to be really immersed in the sociology of medicine in the midst of a pandemic. And that was another thing, the way that talking about trans medicine offered an opening to talk about the medical system in general and how it impacts all of us.

So I think this might be a good time to take a little pause. Some of our listeners might not know some of the language that we're using. Can you help us understand what language we use now, especially in relation to trans medicine and the trans community, and how that has changed over time.

stef shuster

Yeah, no, that's a great question. We could, you know, we could probably chat for hours about how language changes, but you're right, it can be confusing, partly because it changes so quickly, right? So when I use terms like trans or transgender, I'm really referring to people who are whose assigned sex at birth and their gender identities do not align in the way that we expect. So for example, someone who is assigned male at birth we expect will grow up and identify as a man, and when that is not aligned like that tends to be. A term that we would refer to is like being trans right? I try to keep my definitions really open, partly because you know. A year from now, all of the terms might change again. And like it's interesting to think about how language matters, not just in this conversation, and not just for people who are listening to like understand, but also these are questions that medical providers have to so right now, for example, nonbinary people, non binary people are those who do not identify as women or men, but something outside or beyond those binary categories. So when we talk about binaries, we're talking about women, men, female males, etc. The term nonbinary really, I mean like it's hard to pinpoint because, time feels a little strange right now, but I I would put the development in the, you know, the circulation of the term nonbinary. I would date it about a decade and it became a way for people within trans communities who might not be seeking to transition from woman to man or man to woman, and that helped open up like a whole new playing ground for gender identities. And now there's nonbinary people, and genderqueer and gender fluid, and agender, and there's probably 1000 more if we go back to the 50s and 60s.

Those terms did not exist, and the terminology that was used at the time, really it was transsexual and that developed out of distinguishing between--

and again, this is like the language they use at the time--

transvestites, who people we might now refer to as cross threat, like people who cross dress and then transsexuals, and the way that they understood it back then, is that transsexuals were people who sought medical interventions to change their, their gender at like the body level.

Stephanie Solomon

I wonder that leads to the question of where are medical providers and I know a little from reading the book, but found this really interesting. Where are medical providers in understanding gender affirming interventions for non binary people?

stef shuster

Yeah, I mean it's really thrown some of them for quite a loop. So if we think about, again, going back to the 50s and 60s, the entire body of knowledge that was established at that time about what trans medicine—it was all oriented around offering hormones, either estrogen or testosterone, to people to transition from man to woman or woman to man and that way of thinking about trans people in trans medicine has persisted for 70 years. And in the last 10 you know even providers that I interviewed who were like, I have 10 years of experience, I've had a lot of trans clients and I at this point feel like I have a pretty good understanding of how to work with trans people. And then there's nonbinary people, and I just don't know what to do. And I'm like, oh, this is so interesting. Like, this is yet another moment where their knowledge about what they're supposed to be doing or how to work with trans people has once again been, you know, upended. And there are some medical providers who respond by leaning into some of that flexibility and the way their patients identify their gender is it's not important to them. Instead, they they want to meet their patients where they are and there's others who are like that's not—being nonbinary is not a thing, you have to pick. You know, like, “Are you a trans person or not? Because this nonbinary thing is is, just a phase.” And those are providers that I, I think they have difficulty with ambiguity.

Stephanie Solomon

I would like to stay a little bit more in the history of this conversation. And I'm thinking a lot about the stories that were told through the letters, and I'm wondering who got access and who didn't get access to trans medicine. And are you willing to share some of those stories?

stef shuster

Yeah, I mean it's a really, you know it's a really troubling history and the reason why I wanted to go to the Kinsey Institute archives and really dig around is that you know I was going to these trans health conferences and I kept hearing stories of progress right, and I think a lot of times we like to believe that social change in time unfolds in a linear—you know, that things improve over time, and so I kept hearing that over and over in these obscure references to the dark days of trans medicine, and I was like, well, I kind of want to know more, because at that time there were only a couple of histories written about trans history, of which medicine is one part so I, you know, I went to the archives, and I mean I would spend weeks and weeks poring over these letters and taking notes and looking at the patterns and the story that started emerging is that medical providers in the 50s and 60s they were up against several challenges. One, they didn't have much knowledge, right? There weren't a lot of providers. Like there were a handful of providers who wanted to work with trans people or were willing to work with trans people, but they still didn't know what they were doing and they also faced criticism from their colleagues.

So here we have a 1950s understanding of trans people, which often people assumed that trans people were delusional, right? It was assumed like you just woke up one day and wanted to change your gender. Like clearly you have a mental health issue. Some of the providers colleagues also thought that maybe they were delusional, right? Like why would you, why would you entertain the delusions of this group of people like send them to the therapist?

So they felt like they needed to find ways to justify what they were doing, I think partly to themselves and also to those colleagues who are really critical of their practice. And so they started setting up a way of thinking about trans people that was very narrowly defined, right? People that they were willing to work with were more often white, they were more often gender conforming, meaning that if someone was transitioning towards being a trans woman, they needed to be feminine—ideally, hyperfeminine, held a job that also was in a feminine occupation, was middle class, had no children, that's a whole other conversation and wanted to be involved with men so that they would be heterosexual right upon transitioning.

Anyone who was outside of those race, class, occupational status, familial status had a very difficult time accessing gender affirming care and part of it was because providers again, were so concerned about their own legitimacy and their own standing in the medical profession. That they wanted like they that some of them even referred to that patient as like the ideal patient, the credible patient, the worthy patient, and anyone who is outside of any of those different categories was immediately flagged as maybe not, and I'm using air quotes here. Like maybe not really, truly a trans person, right? And they should definitely go seek the help of a therapist.

[break]

Stephanie Solomon

I'm Stephanie Solomon. For those of you just joining us, I'm speaking with Stef shuster, the author of Trans Medicine: The Emergence and Practice of Treating Gender. Stef shuster is an assistant professor of sociology at Michigan State University. So something that really frustrates me as I've been back in this world of academia and thinking about public health, is this assumption that there's a normative way of being in the world. So many of the healthy habits and I would use air quotes there too, even though folks can't see me. You know, if we just tell people if you could do this or be like this, then your health issues will disappear.

So in my own life, gatekeeping has shown up in doctors not believing my pain, telling me to run miles outside, instead of addressing serious endometriosis. I'd like to hear from you how that gatekeeping has changed over time, because I did feel a sense of of sadness and there was a lot of cruelty in some of the stories. But I also felt a sense of hope about the ways that gatekeeping is shifting. So if you could talk a little bit about that.

stef shuster

Yeah, yeah, absolutely. I mean, I, I think that's something you know. And just as you were talking an important point here is that while the description that I just offered was for, you know, the so-called ideal trans patient that those same criteria of race, class, gendernormativity, heterosexuality are also things that many other groups contend with. And not being able to uphold those is sometimes met with the force of the medical establishment, right?

So as like as I was writing the book—I will get to your question.

Stephanie Solomon

I believe you.

stef shuster

But as I was writing the book, I was thinking a lot about, you know, not only what is this a case of for trans medicine, but how does it tell us something about other areas of medicine? I think a lot about people who have chronic pain, right? And we hear so many stories about people with chronic pain being dismissed by the medical establishment. Often the people who are dismissed are women, right? Women’s pain apparently is not as important to take seriously. We hear that about the ways that, I don't know, like hysteria kept coming up for me, especially as I was grappling with the archives because that was a clear case of women who were sexually active who were not upholding—you know, like the feminine ideal women who were not compliant to their husbands whims, like back in the 1800s were labeled as hysterical because of their wandering wombs, and either sent off to an asylum or locked away in a room like out of sight out of mind.

That way of using the authority of medicine to punish people into compliance is not just exclusive to trans medicine, right, or trans people. I think that your question about gatekeeping reminds me of that as well, right? So there's a lot of different communities, patient groups that experience gatekeeping in pretty incredible forms, right? So for trans people the way that that shows up, it has changed since the 1950s and 60s, right so like in the 50s and 60s, again through Harry Benjamin and his colleagues swapping information about, here's how to work with trans people. Again, we have to remember it's through their clinical experience that they're setting up these guidelines for how to work with trans people. It's not based, it's not supported by data. You know it was more just what they felt comfortable with, so they would set up—if a trans person approached Harry Benjamin he would say “OK. Go speak to a therapist. I am asking you to do six months of therapy. And then that person will sign off and if they feel like you're ready, then come back to me and I might consider allowing you to start hormones.”

So that process has eased a little bit right now in contemporary medicine, but there still are some providers who more or less follow that guideline, right? And so it makes sense in some ways. You know, in the 80s and 90s we had to turn to evidence-based medicine and it makes sense like I want to be very careful here about not insinuating that evidence-based medicine is not an important step in medical knowledge. I want to know if I take a pill, ideally that someone, somewhere has studied what the side effects might be. Aand so just about every medical treatment has evidence to support it, and also what's called a clinical guideline that literally outlines the symptoms and the treatment steps.

So too in trans medicine. Those guidelines were developed in the 50s and 60s based on Harry Benjamin and his colleagues, and while they've eased up such as instead of six months of therapy, now it's—It's not mandated like therapy is not mandated for hormones, instead it's recommended.

But that still kind of gestures towards that there might be something psychologically wrong with trans people to want to transition in the first place.

A lot of trans medicine, I mean our healthcare infrastructure in the United States is so complicated and it's like it's really tough to navigate. And depending on what state you live in, what kind of job you have, if you have health insurance, you might be paying out of pocket, right, for gender affirming care. That is in some ways a form of gatekeeping, right? Yeah, so I would say the answer to your question is, it's difficult because some of those explicit forms of gatekeeping: go speak to a therapist for six months, make sure that you sign off on this and that. That's not quite as present now, but over time, because there has been the introduction of health insurance because there has been like the fracturing of a health care system where there's like so much specialization now that it presents new challenges that also presents new forms of gatekeeping.

Stephanie Solomon

One of the parts of gatekeeping that felt hopeful to me was where, some of the stories that you told about providers who are really listening deeply and trying to make decisions not based on a checklist, but on the expertise of their patients. Is that more of a norm or, it does it kind of depend where you live and—

Stef shuster

It kind of depends on which doctor's office you walk into. Yeah, so if we think about like at the same time that evidence-based medicine was introduced in the 80s and 90s, so too was patient centered care.

So like the idea is that that old model of like Doctor knows best, which is incredibly paternalistic, and that you know if you're the patient, you follow doctor's orders, and that's like, and you should be compliant and not question them like that is a model that has fallen out of favor for a lot of the medical establishment. But what's interesting in trans medicine and undoubtedly elsewhere across, you know, different medical areas is that sometimes when doctors are feeling so uncertain 'cause that's not comfortable for them to feel uncertain--like that “I don't know what I'm doing,” is not comfortable for doctors that sometimes in response to that they kind of double down. And they go right back to that doctor knows best model and impose a very strict interpretation of what trans people have to do in order to access hormones, and especially surgery. And we haven't even talked about surgery, but yeah. But again, like there these are, it's not every provider and I want to be really careful that that we understand that. It sometimes is a little bit easier to focus on the real challenges and the power imbalances and all of the horrible things that have happened. But I don't know, I started ending my interviews with providers with the--It sounds like a simple question, but it really led to some beautiful answers and so I started asking providers, “Can you share with me what are some of the joyful aspects of working with trans people?” And you know, because like because trans people are like are fit, they fit within a marginalization, right? Like they're marginalized groups that though, at least for sociology, we tend to focus so much on like social inequality inevitably equals horrible oppression, right? But we don't really know that much about joy.

And so I started asking providers that too like what are the joyful aspects of working with trans people. And even providers who were a little more strict in their interpretations. And even those providers who offered examples that, to my ears as sociologist, I was like, this sounds more closely aligned with the 1950s and 60s. They had beautiful responses. And they talked about, like, they talked about how they they felt like they were better doctors through their work with trans people.

And I'll just offer an example or two because I think this is also just a loop back. You know, towards the beginning of our conversation there is something to be learned from trans medicine about medicine in general, right? You know, like there were a number of doctors who talked about, I am aware that there is deep mistrust among trans people when they show up in healthcare, and I know that and so I feel compelled to really slow it down and establish rapport with my patients and get to know them. And I don't know if you know, I don't know if you've been to a doctor recently. Or any of the folks who are listening. But like it's usually, I don't know 7 to 12 minutes. You check in. You fill out some forms. You go into the waiting room. And once the doctor comes in, seven minutes later, it's finished and it is incredibly difficult to establish rapport with anyone like in that time period. So these doctors were kind of reflecting on, you know, given that I know that trans people have a lot of mistrust and I want to establish rapport. I have to slow it down and seven minutes is not going to cut it. And then what they found is like they talked about how, “I learned that from my patients from my trans patients, and I actually want more time with all of my patients. I want to know my patients better.”

So yeah, so there are a lot of challenges, but I think that, that providers feel like they learn a lot from their trans patients in how to be better doctors.

Stephanie Solomon

I love that so much because it's—there's difference and challenge that what you were talking about with folks wanting things to be black and white, or to be really clear cut and that a practitioner would walk into a room, and because that that difference is there, it moves to trust-building and relationship-building and I—as a human that goes to doctors offices, those are the best experiences where you feel like you're being seen as a whole person, and I understand the way that our system you brought up the complexity that that makes it challenging for that to happen. But it is a balance to some of the history and present violence and cruelty that trans folks experience in the medical system. That balance of the joy and the trust and the relationship-building. I really feel that when you talk about that I'm I'm glad you're sharing that with me and and our listeners today.

So moving kind of in that direction, I'm wondering if some listeners might be thinking we're talking about such a small population, and when we're talking about trans folks, so why should I care? Why would a general practitioner care and what does your book teach us about the wider population and you've gone into that a bit, but I'd love to hear, hear a little more about that.

Stef shuster

Yeah, I mean the best estimates are that trans people make up .6% of the total population and not all trans people seek physical transitions, right? So it might even be smaller. Given the the extreme, like, the extremely small percentage of people--and I've heard this question before and I've really had to think carefully about it. Because I think on one hand, the question might accidentally be shaped by the assumption that because the trans population is so small that we therefore are inconsequential, right?

But I think that part of my answer is about, you know, like we are having so many conversations, I think, currently about health inequalities and which groups face just enormous health disparities, and it's usually about like race and class and gender and size. And a couple of other different factors. So partly why we should care about what happens to trans people in health care is because it reflects attention on some of the flaws in the system of health care itself.

So why do some providers mistreat trans people? It’s because of bias. It's hard for me to imagine that, and often it's not like sometimes it's not even intentional, right like this is where, like, nonconscious bias comes out a lot is if you are faced with a person like the person standing in front of you and you don't know how to make sense of them and you don't know which box to put them in. In those moments, sociology consistently demonstrates that the person with more power does everything they can to rearrange that situation so that it works for them, and it makes them feel more comfortable, right? And that like, that's where bias plays out. It's why, like across all these different marginalized groups, in healthcare, like why healthcare? Because there is power differences between doctor and patient. Even for those doctors who want to work in, like a patient-centered model, they still are the ones who have to make decisions and write and write prescriptions, and you know. And some of that process might be facilitated with their patients, but they still are responsible for that patient's health.

So I would suggest that understanding the experiences of trans people in health and understanding how providers understand or sometimes continue to misunderstand them tells us a lot about health care in general.

[break]

Stephanie Solomon

I'm Stephanie Solomon. For those of you just joining us, I'm speaking with Stef shuster, the author of Trans Medicine: The Emergence and Practice of Treating Gender. Stef shuster is an assistant professor of sociology at Michigan State University.

Stef shuster

You know there has been movement recently for doctors to become better at like bedside manner, right? But even if you're trained and trained yourself to, you know have better bedside manner. It's still when that unexpected element comes up in your practice that all of that bias comes like raging out, right? Because it feels uncontrollable so.

Stephanie Solomon

Oh, thank you for that, I think, I think that so much of what you're touching on speaks to me as somebody really passionate about health equity and what does it mean for us to meet folks where they are when we have many different populations with different needs, and then the desire as a culture to kind of create monoliths of folks. So thank you for that.

So in your book, you talk about two different kinds of providers, and this was something I think probably because of my own life experience navigating healthcare that that I really focused on in my reading. Those who are close followers and those who are more flexible and you've talked a little bit about that, but I'm wondering if you could talk more about how those interpretations really enfold and impact individuals.

Stef shuster

Yeah, so in the book and you know, interviewing providers and watching them at health care conferences, there really are— And of course there's overlaps, so these are just like terms to think about how providers manage their uncertainty differently, right? So there are some who, when confronted with uncertainty and feel like they don't have much expertise, will closely follow those clinical guidelines that I was talking about step by step because they want assurances that they're doing the right thing. They want assurances that their own reputations will not be called into question and they want assurances that, like that question of, “Is the person standing before me again,” airquotes “truly trans,” continues to haunt some providers today.

And one way to kind of shore up that doubt is to follow those clinical guidelines step by step. First ask the trans person to go to a therapist. The therapist signs off. Once they sign off, then have the trans person come back to me. Do they have any illness is where it gets really interesting. They use the language of co-occurring conditions. And if you think about it. And I asked some of them, you know, they would say, well, if a patient has co-occurring conditions, I really want to make sure that we take care of that other stuff first. And I really I really try to listen with an open mind and just ask them questions and help me understand their experience. And so I would say, “Oh, that's really interesting. Can you share more about what you mean by co-occurring condition?” And they would say, “well, you know if I have a patient who comes in who has depression and also is seeking you know hormones, I want to take care of the Depression first and then I'll consider letting them start hormones.” Because the guidelines say you know the patient should be reasonably healthy, et cetera, et cetera. I think one of the sticky points about that way of thinking like closely following that gu,t following it to a T, is that it sets up first of all, an unreasonable burden on trans people, right? Like trans people have have health issues. Trans people get pink eye. They break their bones. They have sinus infections. They might have depression, whatever. Uhm, but the idea like it's very subtle, but think about it right, co-occurring is a label that's used to describe people who have multiple conditions.

And so it insinuates that being trans within itself is a condition is a health problem, or is a mental health problem.

While we like to think that that that way of thinking has kind of, you know, been left in the dustbins of history, I think that it still shows up in some of the providers’ decision making. And what it also reflects is just the vast amount of uncertainty they have and wanting—again they want to do right by their patients. But they also have difficulty breaking out of that strict interpretation of the guidelines so those are like the close followers. The flexible interpreters are those who lean more comfortably into the uncertainty and follow, you know, more of a model that sounds something like, “You are the expert over your gender identity. I am the provider who is going to help work with you through this process, right?”

So like this is another interesting sticky point in trans medicine is that, Who is an expert over gender identity? Because medical providers are not trained in gender identities. You know, like if I have a legal issue, I'm going to go to a lawyer and if I have a toothache I'm going to a dentist and in some ways I would say if I have a gender identity question, it's a little weird to go to a medical provider. It's like maybe we should all go to the gender studies professor, right? So it's just yeah, it's it's interesting that, like they've kind of been tasked with making decisions about a gender identity, which is an area that they're just really not trained in. So those terms describe those who lean more comfortably into patient as expert over their gender and those who faced so much uncertainty they kind of doubled down on their authority and go back to that doctor knows best model and follows the guideline to a T.

Stephanie Solomon

So there was a piece in there where you talked about this subtle idea of being trans as being a health care issue and that makes me want to ask my last question, which is, what is it like to study a population that you are a part of?

Stef shuster

Wait, that's your last question? That's a huge question. Uh, you know I I, at moments it can be challenging, sometimes the cognitive, emotional, professional energy that you know, it's like I'm a trans person in my personal life and I'm I'm a scholar who studies trans people in medicine and so sometimes it's like trans all the time.

I think that, I was committed to not—to not presenting providers who offers at moments distasteful comments or ideas like in a negative light because that is a part of their experience. I think I'm also a little bit too much of a sociologist like I don't want to ascribe judgment onto providers. But I rather want to understand the patterns in the ways of thinking and the challenges they experience. And sometimes it can be difficult, because I have had those experiences in health care where I show up with vertigo, because I moved to a place that had a really high pollen count that I had never been exposed to and six months later I'm still going to the doctor every week. Different doctors every week and all they want to talk about is the fact that I'm a trans person. And it's like well, can we talk about my vertigo? You know like that, actually isn't—that's prohibiting me from doing my job. It's very difficult to teach while you have vertigo. Yeah, so sometimes it's it is a little tricky managing my personal life and experiences and how it maps onto some of the scholarly conversations I'm involved in, but I think in some ways it strengthens who I am as a scholar, and I think that part of that is because I have a commitment to not—I don't want to play the gotcha game right? I I want my work to speak back to an audience of not only academics and not only you know folks like you and like my brother or like just the the general person I want my work to speak back to providers. And if I played that game of like you know, trying to portray providers who I disagreed with, like in a negative way, I don't think that they would be able to hear the work or take it in or reflect on it. So I think I do it as well as I can. Sometimes I'm human, so not always, but I think if anything it's enriched the work that I do, and in some ways the work that I do has enriched who I am personally.

Stephanie Solomon

I can attest to that.

Alex Chambers

That was sociologist stef shuster, talking with Stephanie Solomon about their book Trans Medicine, published in 2021 by NYU Press. If you want to know more about stef shuster’s book, we’ll link to it on the website.

You’ve been listening to Inner States from WFIU in Bloomington, Indiana. If you have a story for us, or you’ve got some sound we should hear, let us know at wfiu.org/innerstates.

Speaking of found sound, we’ve got your quick moment of slow radio coming up. But first, the credits.

Inner States is produced and edited by me, Alex Chambers, with support from Eoban Binder, Aaron Cain, Mark Chilla, Michael Paskash, Payton Whaley, and Kayte Young. Our Executive Producer is John Bailey.

Special thanks this week to stef shuster and Stephanie Solomon.

Our theme song is by Amy Oelsner and Justin Vollmar. We have additional music from the artists at Universal Production Music.

I want to acknowledge and honor the Miami, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Shawnee people, on whose ancestral homelands and resources Indiana University Bloomington, home of WFIU, is built, as well as the generations of workers who built it.

All right, time to go listening.

You’ve been listening to cicadas, out after 17 years.

Until next week, I’m Alex Chambers. Thanks for listening.