I Bite My Thumb at Thee! Â

We're going against the grain with some of the most radical musical diversions from the norm, courtesy of bold, iconoclastic, or legitimately insane composers. Bending or almost breaking most rules of composition seemed to be on the agenda for these off-the-beaten-path visionaries. Plus, we're featuring a recording in which Austrian baroque violinist Gunar Letzbor provides his renditions of Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber's cherished "Rosary Sonatas."

We'll hear more from Gesualdo later in the hour, along with others who definitely pushed the envelope with their musical stylings.

Ars subtilior: The New "New School"

In the late-14th century, the Roman Catholic papacy found competition in the installation of an antipope, Clement VII, in Avignon, France. This "Western Schism" touched off a series of physical, political, and spiritual conflicts, but for artists surrounding Avignon at the time, it meant a lot of attention from an opulent court!

Eager to impress, musicians composed elaborate works of rhythmic and textual subtlety, pushing the absolute limits of the notational system that they knew. This resulted in vocal works that would not sound out of place at all within the spectrum of twentieth century concert music.

Texts to these songs intentionally provided double entendres, puns, shadowy allusions, and labyrinthine metaphors to describe current events and to glorify public figures, not least of whom was the antipope himself.

These composers were very well aware of how much they were breaking the mold, though, and they channeled this self-conscious attitude into their music.

Let's listen to two of these works. Both complain about composers who took up new noteshapes and trends in theory, but what's so ironic is that, despite railing against those noteshapes, the manuscripts that contain these pieces use them!

'Baldi's Scalding Difficulties

Knowing that you're pushing the envelope is one thing, but knowing that you're an excellent composer and flaunting it on the page is another thing entirely.

Seventeenth-century organistand composer Girolamo Frescobaldi was a child prodigy who struck out on a crooked path away from the theoretical practices of his time, and the freedom with which he composed is remarkable even by today's standards.

Frescobaldi frequently left cheeky notes to the would-be performer concerning his skillful and often hair-raising techniques. One in particular, a toccata from one of his books of keyboard music, offers the witticism:

"Not without toil will you get to the end."

[The performer, Jean-Marc Aymes, is working on a comprehensive survey of all of Frescobaldi's keyboard music, which includes the CD containing the track we just heard.]

The ever-inventive Frescobaldi completed a collection of sacred keyboard music in 1635 that includes three organ masses, as well as some totally unrelated glosses on some secular tunes. He entitled the collection Fiori Musicali, or "musical flowers."

Even in sacred music Frescobaldi had a unique angle that challenged the theory and practices of his time, and most of this collection established a precedent for keyboard composition that would persist well into the nineteenth century.

In this movement from one of the organ masses, Frescobaldi leaves a cryptic written instruction to the performer that reads:

"He who can understand me, will understand me; I understand myself."

The coded message, along with a fragment of music at the head of the movement, signals the performer to sing the line of vocal music at certain points during the organ music. Frescobaldi, of course, never divulges what those points are! He leaves it to the performer to solve the puzzle.

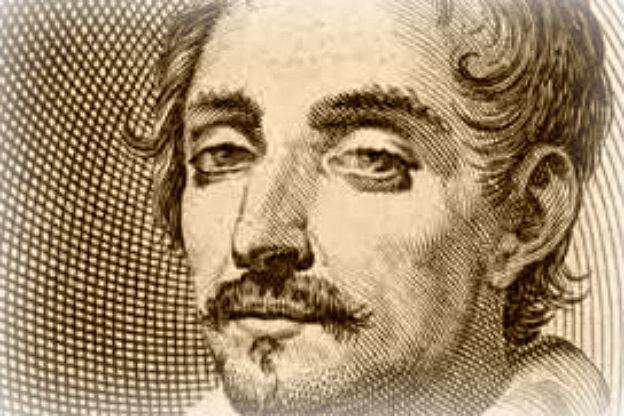

Mad Ol' Carlo

Not to "rub you the wrong way," but we're listening to divergent and radical music this hour by composers who just couldn't help rebelling against the norm.

Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa and firebrand composer, went to "neck-breaking" lengths to develop his unique madrigal style, which is a far cry from anything else composed at the time – and rightfully so, given his precarious mental state.

For starters, he married his first cousin, caught her having an affair with another nobleman, murdered them both in the bed, and displayed their bodies prominently on the steps of his estate. It was some years after this incident that his most radical compositions appeared in his fifth and sixth books of madrigals.

The jarring dissonances, the almost 20th-century-sounding harmonies, and the intensity of expression in his musical language all point to an insanity that was immortalized in police and eyewitness accounts of his gruesome crime.

Luckily for Gesualdo, he escaped prosecution due to his noble standing. This enabled him the freedom to sequester himself away in his castle, with the financial resources to hire an entourage of singers and instrumentalists to keep him entertained with his own compositions.

Gesualdo's bloodstained and passionate fury mellowed into severe depression and guilt throughout his self-imposed isolation. It's documented that he requested to be beaten several times a day by his servants. Musically, he channeled his crippled psyche into a powerful set of madrigali spirituali, madrigals that are secular in musical style but sacred in their choice of texts.

His settings of the responsories to the readings of Lamentations during Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday run a psychological gamut of emotions. Some of the darkest parables and stories of the Biblical calendar are given emotionally arresting settings by Gesualdo, deploying the same harmonic and rhythmic dissonance that remained unparalleled for several centuries.

Featured release: Gunar Letzbor performs Biber

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber died in 1704, but he continued to cast a long shadow across the possibilities of violin technique for generations. His compositions frequently challenged even the most taxing of violin literature at the time, employing multiple stops during tricky passages, as well as a method of retuning the violin's strings called "scordatura."

A set of 15 short sonatas that he composed follows the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary, and each sonata is notable for having its own unique scordatura tuning to alter how the violin sounds and what it is capable of accomplishing.

Let's hear one of these "Rosary" or "Mystery" Sonatas, performed by Gunar Letzbor, a Baroque violin specialist from Biber's adopted home country of Austria.

There's actually a sixteenth work added on to the succession of these sonatas, and unlike the first 15, which are intended for solo violin and an accompanying ensemble, this last work, called a "passacaglia," is for a violinist alone.

It's one of the first unaccompanied solo works of its kind for the instrument, and it set a standard that would be emulated by eminent composers for centuries afterward.

Break and theme music

:30, Frescobaldi: Il secondo libro di Toccate, Canzoni alla Francese, Jean-Marc Aymes, Ligia 2009, D. 1, Tr. 4: Aria detta la Frescobalda (excerpt of 2:41)

:60, Frescobaldi: Il secondo libro di Toccate, Canzoni alla Francese, Jean-Marc Aymes, Ligia 2009, D. 2, Tr. 2: Partite sopra Passacagli (excerpt of 1:51)

:30, Biber: Sonaten Uber Die Mysterien Des Rosenkranzes, Gunar Letzbor/Ars Antiqua Austria, Arcana 381 (2015), Mystery Sonata No. 4 in D minor "The Presentation of the Infant Jesus in the Temple": D.1, Tr. 10: Ciacona (excerpt of 6:37)

Theme:Â Danse Royale, Ensemble Alcatraz, Elektra Nonesuch 79240-2 1992 B000005J0B, T.12: La Prime Estampie Royal

The writer for this edition of Harmonia is Benjamin Robinette.

Learn more about recent early music CDs on the Harmonia Early Music Podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes or at harmonia early music dot org.