[Theme music begins]

Welcome to Harmonia . . . I’m Angela Mariani.

This week, Harmonia is commemorating Easter. Part of both the masses for Easter Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday, AND the celebration of Vespers on those days, is the antiphon setting of the words from Psalm 118, Verse 24, which begins, “This is the day the Lord has made” and ends with “Alleluya.” We’ll hear the chant itself; then we’ll hear how it changed with the advent of polyphony, going all the way from the 13th to the 17th centuries, travelling on both familiar roads to famous composers like Byrd and Praetorius, and on less travelled paths that lead us to convents and possibly even a daughter of Lucrezia Borgia, who, as it happens, is the subject of our featured recording.

[Theme music fades]

MUSIC TRACK

Le jeu des pèlerins d'Emmaüs drame liturgique du XIIe siècle

Ensemble Organum, Marcel Peres

Harmonia Mundi, France 1990

Anon

tr. 3 Haec dies (4:38)

The Ensemble Organum, led by Marcel Peres, performed their interpretation of Haec dies - the antiphon that begins, “This is the day the Lord has made” - as found in a twelfth century manuscript of a liturgical drama called “The play of the pilgrims of Emmaus,” which tells the story of two disciples of Christ who encounter Him while they were walking on the road to Emmaus.

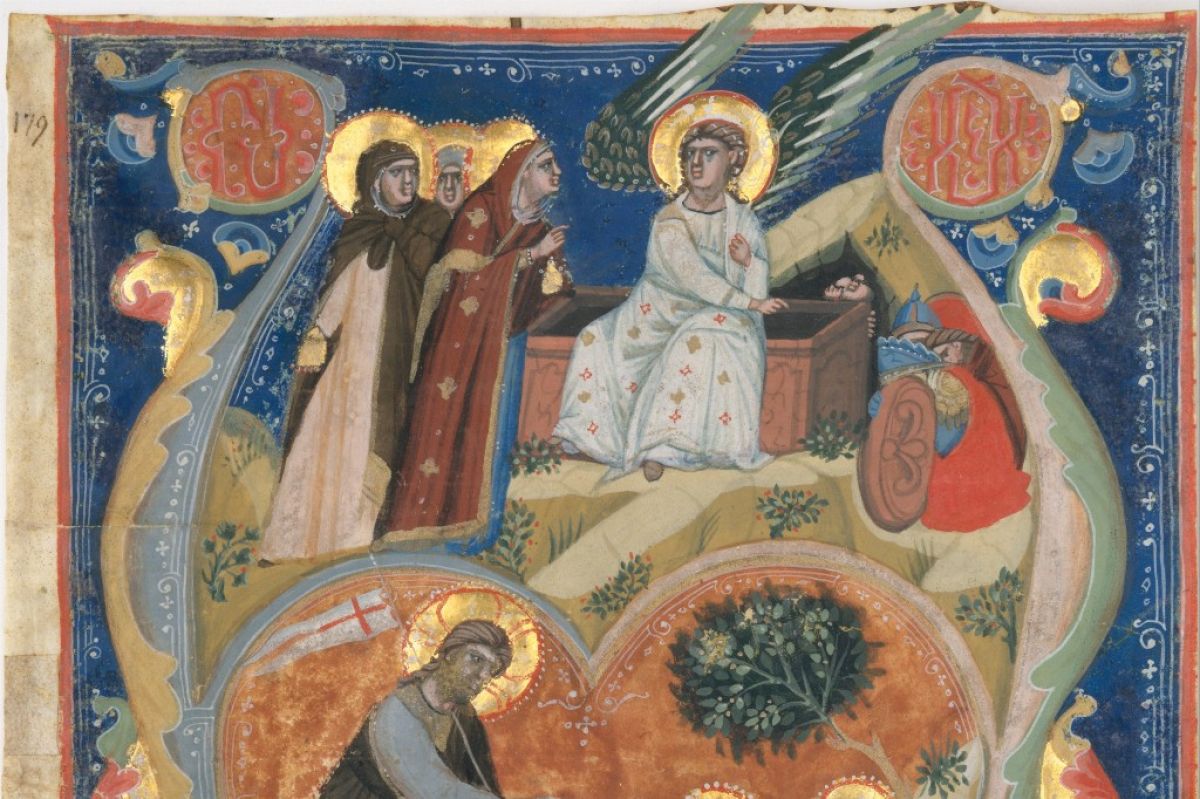

Easter- the most important celebration of the Christian church, celebrating the story of Christ rising from the dead. And it is the chant, beginning in Latin with the words “Haec dies,” Verse 24 of Psalm 118, telling us the good news that forms the basis of this hour’s episode of Harmonia, as we explore its appearances in early music.

The standardization of chant in the Catholic church has been attempted repeatedly over many centuries, from the time of Charlemagne, when chant was the only music heard in church, to the beginning of the twentieth century, when the monks of Solesmes initiated research into early chant notation for exactly the same reason—to bring unity to the liturgy, so that it would be familiar no matter where you found yourself.

Even though not everyone agrees that this style of chant singing sounds the same as it would have been sung in the middle ages, the monks of 20th and 21st century Solesmes inhabit a venerable abbey on whose shoulders we stand—so we’ll begin by listening to them sing Haec dies their way. This track is from sometime before 1972, though we can’t say exactly what year the recording was made, under the direction of Dom Joseph Gajard, a scholar who was at the head of a lot of important chant research.

MUSIC TRACK

Abbaye de Solésmes, Vol 6 - Paques

Choeur des Moines de l'Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solésmes, Dom Joseph Gajard

[Saint Pierre de Solesmes Abbey Monks' Choir]

Decca 2008

Track 6: Anon chant, Haec dies (3:03)

The chant Haec dies is part of the masses of Easter Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday, also taking the place of the hymn at vespers. We heard the monks of the Abbey of Solesmes, under the direction of Dom Joseph Gajard. Thanks largely to the scholarship of those monks, musicologists and musicians began to explore chant in the early days of polyphony. In the thirteenth century, music that was probably largely improvised at the young Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris began to be notated, and for various reasons - political, practical, historical, cultural, temporal - the style travelled all over Europe to other vast spaces. What you are about to hear is drawn from manuscripts in Germany and Italy, but the music is definitely Parisian.

MUSIC TRACK

Mystery of Ancient Voices

Mora Vocis

Pierre Vernay 1993 / B003URMZTY

T8: Anonymous: Haec dies (05:15)

Alternating plainchant with ornate 13th century polyphony, mixing high and low voices in different ways, we heard Mora Vocis perform their reconstruction of an anonymous Haec dies, from the 1993 CD Mystery of Ancient Voices.

And now for a bit of early music-modern music crossover: Let’s hear another Parisian Haec dies, particularly interesting in that it seizes on an early 20th-century assumption that since brass instruments can play very long, clear notes with an unwavering pitch, the long-sustained-note tenors of these pieces were meant to be played on instruments. Of course, that also assumes that singers can’t sing long, clear notes with an unwavering pitch, which is not the case at all, as you’re about to hear: here’s an experienced early music singer, who can most definitely do the unwavering pitch thing, and a member of the Empire Brass Quintet. Breathing is indeed an extraordinary thing.

MUSIC TRACK

Passage 138 BC - AD 1611

Empire Brass Quintet

Telarc 1994 / B000003CZU

Anon

tr. 1 Haec dies (2:01)

Michael Colver sang the chant Haec dies with Ken Amis playing the tuba, on the Empire Brass Quintet’s 1994 Telarc release Passage.

Now, let’s fast forward several hundred years. Heinrich Isaac was commissioned to compose polyphony for the propers of special holy days celebrated in the diocese of Constance, and the project turned into Choralis Constantinus, a collection of 375 motets for the entire liturgical year. Isaac didn’t live to finish the collection, but his student Ludwig Senfl did, and he saw it through to publication in three volumes beginning in 1550. Many smaller churches didn’t even have singers capable of chanting a mass with any competence, but at the other end of the spectrum were large, wealthy musical establishments like Constance where the singers were capable of singing (and maybe even improvising!) polyphony of the highest order.

MUSIC TRACK

Heinrich Isaac: Missa Paschalis (Easter Mass)

Ensemble Officium, Wilfried Rombach

Christophorus 2012 / B0074Y2Z62

Heinrich Isaac

Tr. 4 Haec dies (5:54)

Plainchant complements the polyphonic antiphon at the beginning and end of Isaac’s 4-voice Gradual Haec dies, sung here by the Ensemble Officium, directed by Wilfried Rombach.

The anonymous Musica quinque vocum: motteta materna lingua vocata. was published in Venice in 1543. There’s good reason to speculate that the composer was a nun, possibly part of the convent of Corpus Domini in Ferrara. The princess Leonora D’Esté, an accomplished musician, had formally entered Corpus Domini in 1523 at the age of eight, shortly after her mother died, and she became its abbess by the age of nineteen. Could this be her music? Oh yes, and her mother was none other than Lucrezia Borgia! Here is the anonymous Haec dies from that collection.

MUSIC TRACK

Lucretia Borgia's daughter: princess, nun and musician motets from a 16th century convent

Musica Secreta and Celestial Sirens

Obsidian 2017 / B01N6IU06PB0074Y2Z62

Leonora d'Este (?)

Tr. 3 Haec dies (5:53)

Is this text painting? Joy erupts in the city on Easter Sunday—the bells have been silent all of Holy Week, and now they peal from different bell towers, represented by voices cascading alleluias in conflicting modes a semitone apart! Musica Secreta and Celestial Sirens performed a version of Haec dies that might be by Leonora d’Esté on their 2017 Obsidian release. We’ll be hearing more from this recording later in the hour.

[Theme music begins]

Theme Music Bed: Ensemble Alcatraz, Danse Royale, Elektra Nonesuch 79240-2 / B000005J0B, T.12: La Prime Estampie Royal

Early music can mean a lot of things. What does it mean to you? Let us know your thoughts and ideas. Contact us at harmonia early music dot org, where you’ll also find playlists and an archive of past shows.

You’re listening to Harmonia . . . I’m Angela Mariani.

[Theme music fades]

:59 Midpoint Break Music Bed:

O dulcis amor, La Villanella Basel, Ramée, 2007/ B00082ZR58, Caterina Assandra, Tr. 2 Ave verum corpus (just the first minute of 3:13)

Welcome back. We’re listening to settings of Psalm 118, verse 24, whose words form part of the Easter Mass.

You can’t mention Haec dies without touching on one of William Byrd’s most recorded, most performed works. Byrd employs intriguing rhythmic complexity that adds excitement to the joyous nature of the work.

MUSIC TRACK

Byrd: Cantiones sacrae

Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge, Richard Marlow

Chaconne/Chandos 2007

William Byrd

Tr. 1 Haec dies (2:12)

Richard Marlow conducted the Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge, in William Byrd’s 6-voice Haec dies. In the interest of looking outside the canon, as it were, we would be remiss not to mention Byrd’s two other settings of Haec dies, one in three parts and one in five, of which we’ll hear the smaller now.

MUSIC TRACK

William Byrd Edition Vol 6: Music for Holy Week and Easter

The Cardinall's Musick, Andrew Carwood)

Universal Classics 2015 / B000058UUB

William Byrd

Tr. 12 (Cant. Sacrae) Haec dies (1:14)

The Cardinall’s Musick, directed by Andrew Carwood, sang a little-known trio setting of Haec dies by William Byrd.

Little is known about Caterina Assandra, but she, too, lived most of her life in a convent. Only two motets from her first collection of songs, dated around 1608, survive, and only in German organ tablature, a clear indication that at least some people thought that playing chant on instruments was perfectly appropriate. Let’s listen to an instrumental version of her 2-voice Haec dies from her second collection, Motetti a` due, e tre` voci (1609) played on recorder and keyboard. Following the practice of the time, the recorder player Claudia Nauheim made her own ornamented version of the piece.

MUSIC TRACK

O dulcis amor

La Villanella Basel

Ramée 2007 / B00082ZR58

Caterina Assandra

tr. 3 Haec dies (4:03)

Claudia Nauheim created her own recorder diminutions for Caterina Assandra’s Haec dies on La Villanella Basel’s recording “O dulcis amor,” featuring music of women composers of the seventeenth century.

Let’s go for a grand seventeenth-century finale with Michael Praetorius’ twelve-voice, triple choir, festive, gigantic Haec dies.

MUSIC TRACK

Praetorius, M.: Easter Mass

Weser Renaissance Bremen, Manfred Cordes

CPO 2017 / B01K8LS43K

Michael Praetorius

Tr. 16 Haec est dies (5:56)

Weser Renaissance Bremen, Manfred Cordes, director, performed Michael Praetorius’ 12-voice Haec dies, from their recording of the Praetorius Easter Mass.

Let’s turn once again to the collection Musica quinque vocum: motteta materna lingua vocata of 1543, the earliest published polyphony we can be certain was intended for nuns. It provides the repertory, not to mention a very catchy title, for our featured release the 2017 Obsidian CD titled Lucretia Borgia's daughter: princess, nun, and musician – motets from a 16th-century convent, performed by Musica Secreta and Celestial Sirens.

You’ll recall that Lucrezia Borgia’s daughter, Sister Leonora, was abbess at a convent in Ferrara, where she spent nearly her entire life—and she was an accomplished musician. She had a clavichord, a harpsichord, and an organ in her apartments. Textual evidence connects the book of motets with her convent, Corpus Domini of Ferrara--a Franciscan order following the Rule of St. Clare--and therefore, with her. The motets, composed for equal voices, are some of the most progressive music to be published in the 1540s.

One of the motets, Salve sponsa dei, contains a slow cantus firmus that is not chant derived, but seems to be a singing exercise. The antiphon is to St. Clare the “bride of God.”

MUSIC TRACK

Lucretia Borgia's daughter: princess, nun and musician motets from a 16th century convent

Musica Secreta and Celestial Sirens

Obsidian 2017 / B01N6IU06PB0074Y2Z62

Leonora d'Este

Tr. 7 Salve sponsa dei (2:02)

That was the motet Salve sponsa dei, now officially “attributed” to Leonora D’Esté thanks to award-winning research by Laurie Stras.

Let’s end with a hypnotic, juicy motet in which St. Roch (the patron of dogs, plague, and pestilence!) is beseeched to [quote] “deliver us from the plague and grant us moderation of the air.”

MUSIC TRACK

Lucretia Borgia's daughter: princess, nun and musician motets from a 16th century convent

Musica Secreta and Celestial Sirens

Obsidian 2017 / B01N6IU06PB0074Y2Z62

Leonora d'Este

Tr. 14 O beate Christi confessor (3:45)

Musica Secreta and Celestial Sirens perform O beate Christi confessor, attributed to Leonora D’Esté, as is all the other music on our featured recording, the 2017 Obsidian release Lucretia Borgia's daughter: princess, nun and musician -- motets from a 16th century convent.

[Fade in theme music]

Harmonia is a production of WFIU and part of the educational mission of Indiana University.

Support comes from Early Music America: a national organization that advocates and supports / the historical performance of music of the past, the community of artists who create it, and the listeners whose lives are enriched by it. On the web at EarlyMusicAmerica-dot-org.

Additional resources come from the William and Gayle Cook Music Library at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music.

We welcome your thoughts about any part of this program, or about early music in general. Contact us at harmonia early music dot org. You can follow us on Facebook by searching for Harmonia Early Music.

The writer for this edition of Harmonia was Wendy Gillespie.

Thanks to our studio engineer Michael Paskash, and our production team: LuAnn Johnson, Wendy Gillespie, Aaron Cain, and John Bailey. I’m Angela Mariani, inviting you to join us again for the next edition of Harmonia.