This October marks half a millennium since the young priest, Martin Luther posted his 1517 Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum or Disputation on the Power of Indulgences, more commonly known as the "Ninety-Five Theses" that ushered in the Protestant Reformation.

Indulgences

During the 15th century, there had for some time, been questions and murmurings from within the Roman Catholic Church about the practice of indulgences—a type of pardon that counterbalanced the consequences of sin with meritorious or good deeds. Indulgences were liberally awarded for good works and acts of devotion. Donations to a charitable cause—hospitals, schools, leper colonies and the like—could also be made, and an indulgence could be granted in exchange. But by the late Middle Ages, the Catholic Church's practice of indulgences became increasingly monetized and corrupt and its penitential aspects tarnished.

As an example, in 1515 Pope Leo X offered indulgences to those who made financial contributions to the renovation of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. And in Germany, a friar named Johann Tetzel began to aggressively market these indulgences. Martin Luther saw in this a dangerous precedent, and took great offense to the practice that he thought misrepresented forgiveness and salvation as something that could be bought or sold.

Luther's 95 Theses

On October 31st of 1517, Luther posted his 95 Theses calling for debate on the issue of indulgences. It would be the start of a long series of controversial writings. In his letter, Luther questioned papal authority, and outlined two ideas that would be central to Protestantism. One, that the Bible rather than Church officials held ultimate religious authority, and two, that salvation came only through faith and divine grace—no human could acquire salvation by a good deed.

Luther also placed a great importance on accessibility: believing that a congregation should be able to participate in church in their native own language, he translated the scriptures into German. In the same vein of democratization, Luther advocated for congregational singing, instead of the pre-reformation elaborate Latin services sung primarily by the celebrant and the choir.

Chorales

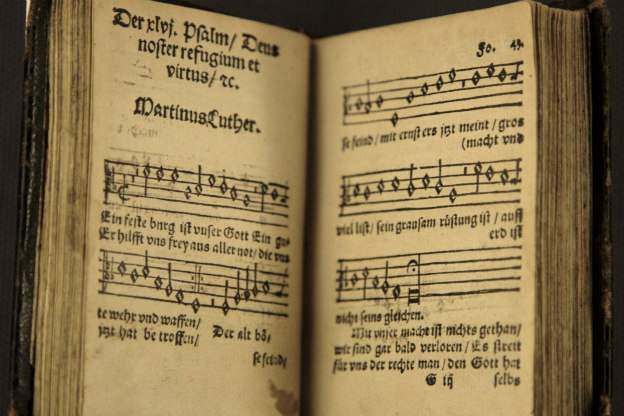

The one-two punch of vernacular language and congregational participation found its synthesis in the Lutheran chorale. The words of these German hymns emphasized key elements of the Protestant theology. Their musical settings were syllabic, simple and strong, metrical and melodic, and by design well-suited for group singing by parishioners. Some chorales were taken from Gregorian chant, or were adapted from popular secular songs and given new words. The majority however were original works composed by Luther or his musical collaborators; a first volume of chorales was published in 1524 by Johann Walter. Perhaps the most famous chorale, and the one that came to be most associated with the Reformation was Martin Luther's ‘Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott'-‘A Mighty Fortress is our God,' based on Psalm 46.

Reformation 500

Celebrations and services abound on this, the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. There are pilgrimages and organized tours to Wittenberg where it all began. There are exhibits and conferences and presentations galore—and the presses are running hot with Luther biographies, not to mention the many, many recordings newly available. Here we'll sample just a few of those new CD's by way of the "anthem" of the Reformation, Ein Feste Burg.

Luther Collage: The Calmus Ensemble

A 2017 Carus recording called Luther Collage, from the Calmus Ensemble opens with the first verse of Martin Luther's original choral melody. For the past 500 years, almost too many composers to count have used this tune as a foundation for their own musical works. One early part setting of Ein Feste Burg was written by Stephan Mahu, a Catholic composer active in Vienna, who nonetheless set some chorales for Georg Rhau's Protestant hymnal of 1544.

Luther and the music of the Reformation: Vox Luminis

"A Mighty Fortress" also features in another recording, this time from Vox Luminis. Titled Luther and the music of the Reformation, it includes Michael Praetorius's impressive eleven minute fantasie on Ein Feste Burg. Born in 1571, Praetorius is most well-known for his dances from Terpsichore, but here we find him delving into the early 17th century's newly minted genre of the Chorale Prelude. The lavish setting is performed on this disc by Bart Jacobs.

Bach's Ein Feste Burg: The Choir of Clare College, Cambridge

Protestantism spread quickly in 16th century Germany, rapidly dividing regions along religious and political lines. Per the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, the Rhineland and Bavaria remained Catholic, but by the time of J.S. Bach in the 18th century, Protestantism was predominant throughout much of Germany. Although October 31st became the official holiday only much later in the 19th century, annual commemorations of the Reformation were begun as early as 1567.

Refashioned from one of his earlier cantatas, Bach's setting of Ein Feste Burg in Cantata 80 was intended for one of these early Reformation Day celebrations.

The Choir of Clare College, Cambridge with Clare Baroque performs a rousing rendition of the 5th movement of BWV 80 on their 2017 Harmonia Mundi release.

Cantata 80 ends with Bach's four-part harmonization of Luther's Ein' feste burg. Given Luther's directives regarding congregational participation, Leipzig church goers likely joined in singing on this final movement of the cantata.

Telemann's Ein Feste Burg: Kammerchor Bad Homburg

Another 18th century composer, Georg Philip Telemann, gives a very different treatment of Luther's chorale in his solo Bass cantata with obbligato violins. While this text and tune are, as we've seen, more often than not, set within the context of Reformation Day, Telemann's Ein Feste Burg was a cantata written specifically for the feast of St. Michael. A world premiere recording of the work was put out in 2017 by Kammerchor Bad Homburg.

Mendelssohn's Reformation Symphony: the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra

Just over a decade after Luther's 95 Theses, the articles of the Lutheran faith, known as the Augsburg Confession, were drawn up in 1530. Three hundred years after that, Felix Mendelssohn composed a new symphony in commemoration of the creed, using Luther's Ein' feste burg as the central theme of the final movement. Nicknamed the ‘Reformation' Symphony, the work was completed in 1830, but missed its planned premiere for the festivities surrounding the tercentennial of the Augsburg Confession. Two subsequent performances also fell through—first in Paris and then in London—before Mendelssohn finally conducted the work in Berlin in November of 1832. But after an underwhelming reception there, Mendelssohn shelved the work, and it was only published posthumously in 1868.

Mendelssohn was a Lutheran convert from Judaism, and drew much of his musical inspiration from Lutheran church music, in particular, that of J.S. Bach. In fact, Mendelssohn championed the music of Bach, and was influential in reviving Bach's music which by the 19th century, had fallen out of style. In 1829, the same year that he would have been planning his Reformation symphony, Mendelssohn led the first performance since Bach's time of the St. Matthew Passion. Mendelssohn was up to his elbows in Bach and Lutheran music during this period of his life, and so in this context, his Reformation symphony comes as no surprise. The Freiburg Baroque Orchestra gives an intrepid period instrument performance of this Romantic work on their newest Harmonia Mundi release.

500 Years of Ein Feste Burg

Martin Luther's Ein Feste Burg has woven its way through 500 years of history by way of many composers. Mahu, Praetorius, Bach, Telemann, Mendelssohn are only the very few at the tip of a very big iceberg.