KAYTE YOUNG: Production support for Earth Eats comes from Bill Brown at Griffy Creek Studio, architectural design and consulting for residential, commercial, and community projects. Sustainable, energy-positive, and resilient design for a rapidly changing world. bill at griffy creek dot studio. Insurance Agent Dan Williamson of Bill Resch Insurance. Offering comprehensive home and auto, business, and life coverage, in affiliation with Pekin Insurance. Beyond the expected. More at bill resch insurance dot com.

(Earth Eats theme music)

From WFIU in Bloomington Indiana, I'm Kayte Young and this is Earth Eats.

This week on our show we have a story from Harvest Public Media about the children of meat packing workers, organizing on behalf of their parents. And we'll hear from growers, grocers and community members in Indianapolis, Louisville and Chicago, reflecting on the importance of grocery stores and fresh produce markets in predominantly black neighborhoods. That's all coming up, so stay with us.

Many of Nebraska's COVID-19 hotspots are meatpacking areas with deep immigrant roots. Advocates say those communities are disproportionately impacted by the virus. But many workers have avoided speaking out about the toll of working during the crisis. As Harvest Public Media's Christina Stella reports, they fear they'd lose their jobs. So, their children are stepping up to organize for them.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] Nhu-y Ngo is a lawyer in New York City, but she grew up in Lincoln Nebraska, moved there with her family from Vietnam as a kid. Her dad got a job at the Smithfield plant in nearby Crete. These days, it’s the biggest employer in town. She says she remembers the sound of his alarm clock going off.

NHU-Y NGO: Sometimes I would have had a bout of insomnia that evening or that night, and I didn't fall asleep. So, then my dad's alarm would go off, you know. And I would see him get up, while I hadn't even gone to bed yet.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] He still wakes up before dawn for work, and over his 27-year long career, she says he's kind of become an institution. He mentors young employees new to the job and is close with his managers - close enough to bring back trinkets when he attended his daughter's graduations.

NHU-Y NGO: Every time we go on vacation which we never do, he'll always wanna buy something for his manager.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] But even as a massive COVID-19 outbreak has gripped the plant with hundreds of reported cases, she says her dad doesn't talk about it much. That's not new behavior.

NHU-Y NGO: They've just put their heads down and that helps them survive.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] Many children of meatpacking workers say their parents are still scared of getting COVID-19, but also worry about getting fired for speaking out. Several companies like Smithfield have issued statements highlighting their pandemic policies, claiming they need or exceed recommendations. But advocates have alleged many plants still aren't socially distancing workers, and don't have enough PPE. Plus, some companies like Tyson still don't offer fully paid sick leave, despite recommendations from OSHA. Those concerns recently brough Maira Mendez, an organizer with the advocate group Children of Smithfield, to the steps of Nebraska's capitol building.

MAIRA MENDEZ: [To the crowd] I stand as the proud daughter of two meatpacking plant workers, who immigrated to this country over 30 years ago with the single purpose to provide the best for our family.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] She told a crowd of dozens that plants are a critical presence in many of Nebraska's immigrant communities, employing thousands.

MAIRA MENDEZ: [To the crowd] These meatpacking plants have made it possible for our parents to put us through college. But we won't allow employers and government officials to classify plant workers as essential workers without treating as essential lives.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] Two thirds of those workers are immigrants, and many of them are Latino. The state doesn't specifically report these numbers, but advocates say immigrants working at plants, particularly Latino immigrants, have been disproportionately hit by outbreaks. Statewide, Latinos make up almost half of Nebraska's COVID cases.

TONY VARGAS: This is a deeply immigrant community that is uplifting local economies and putting food on the table.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] That's Tony Vargas, who represents a lot of plant workers from South Omaha, in the Nebraska legislature. He says the state should have done more outreach earlier on.

TONY VARGAS: It took weeks for us to get Spanish language education material in certain places, let alone at the state level.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] Vargas' parents moved to New York City from Peru in the 70's and worked on factory lines. His dad eventually became a machinist, an essential job - just like the workers at Smithfield. He worked until the day he got sick with COVID, and died a few weeks later at 72.

TONY VARGAS: He relished the American dream. If it wasn't for the American dream, I think he would have lost will and that's what kept him going.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] Now Vargas says his grief feels bigger than him. It's a call to protect meatpacking families that aren't that different from his, from the trauma of COVID-19.

TONY VARGAS: And it's painful for me, (I) can't imagine what it's like for the family members, and for the sons and daughters of workers.

CHRISTINA STELLA: [Narrating] Nebraska doesn't release information about individual businesses, but nearly 35,000 workers have gotten sick with 14 deaths. The children of Smithfield and other organizers say they'll keep speaking out until working conditions improve for their parents. Kristina Stella, Harvest Public Media.

KAYTE YOUNG: Find more at HarvestPublicMedia.Org

(Transition Music)

[Narrating] Last week, in Louisville Kentucky, we spoke with folks remembering Chef David McAtee, at the site of his barbeque stand on 26th and West Broadway. He was killed early last week by authorities amid the violence surrounding protests of deadly policing of the black community. Just two blocks away, on 28th and West Broadway is a Kroger grocery store. On the day I visited the entrance and the windows were boarded up, with a sign saying it would open the following morning. I spoke with a few of the people who were gathered in the parking lot.

MESHORN DANIELS: My name is MeShorn T. Daniels. We are here at 28th and Broadway, Kroger’s. The Kroger’s that got looted, broken into, and damaged because of supposedly angry people who supposedly protesting about a shooting that took place along 26th and Broadway.

It's a couple reasons why I'm out here today. Because they very things that I was concerned with, is happening. We have lost all amount of honor for ourselves. Okay? This is not just about what's happening, with Breona, and the issues with happened with the George Floyd. This is about the lack of responsibility of not allowing other people to cause you the bearing of your own. And I'm disappointed that we allowed ourselves to emotions to get captured. We can have anger, we can have protests, but you cannot tear up your own.

I'm a gentleman that identifies myself as American descendants of slaves. I believe that the problems that we continue facing in this country is because of the misconception of who that demographics of people are. They're not the Negros, they're not the blacks, they're not the African Americans, but they are actually descendants of American slaves that are hurting because they never got that repaired. They never received that reparation. They never got that inheritance. They never got that love and respect to honor them. The things that we have happening and will continue happening until the dominate European culture of America honestly acknowledge that we have descendants of slaves here; American descendants of slaves that need to be treated with the love that their children of their this country, and not just used by this country to be a capitalist society. Okay? And I'm very committed to that in saying that's the problem. This calls for my own country, not being responsibility in handling their responsibility, and thinking it’s gonna be just sweep under the rug or we just, you know as they say, pull our bootstraps up and move on, get along, get over it. It ain't goin to change like that.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Interviewing] What does it mean for the community to have the Kroger closed for right now?

MESHORN DANIELS: Oh, it's going to hurt the community big time. I mean you got elders, elderly people that this is where they get their drugs at. This is on the bus line. This is the lifeline; this Kroger’s is the lifeline to everything to this community. To lose this Kroger’s is... it's horrible. It's horrible. It's horrible. There is another grocery store 34th and Portland. Okay, the next one is Indiana. Okay? Go across... the next one is Indiana. You talking about close, the next closest is in... or 18th and Dixie Highway down there going on Chadly. That’s the next Kroger.

KAYTE YOUNG: A group of people had set up grills and tables near the boarded-up building. I spoke with a woman who identified herself as Jocelyn. She and her young children had made sandwiches to give out in the neighborhood since the Kroger was closed. Jocelyn wanted to tell me about an urban garden project she's involved with called Victory Garden's Urban Farm, located in the Victory California Park Area of West Louisville.

JOCELYN: It's over on Dave’s street, we have an urban garden. Since it's organic, we gonna have like fruits and veggies, we gonna have chicken eggs, and everything we need for moments like this one. If you don’t have fresh access, and we plan on donating most of it to the elderly or the sick in the community. And for the rest of it we'll be selling at Farmers' Markets that we're gonna set up in the West, because the West end doesn't see too many like Farmers' Markets. So, we plan on doing that too but... you know, we do what we can. We grow our own food; I grow at my house. Ebony grows at her house, her sister Angela also grows at her house, and then we grow all three together in the Urban Garden. So, between the four of those gardens we plan on supplying as we can of organic produce. We've actually been individually gardening for some time. We actually started the Urban Garden because of the response like this, we heard about Kroger, pulling out. We know we don't have many fresh stores around here and if you're going to this store, like it's not kept like other Krogers' in other areas. And you know, it's a lot of elderly in this area who are sick and don't have transportation at all times. So, we was gonna do kind of like a subscription thing where we can get to them, you know, every few weeks, or every month, or it depend on the need of the supply and make sure they have like the produce and stuff that they need.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Interviewing] Is the Kroger planning to leave the community anyway or...?

JOCELYN: There was a rumor before the corona hit, I'm not sure what they were gonna do, or actually I tried to call the Kroger corporate a couple times today. I went to the Kroger on Dixie and they gave me someone’s information to contact, she was already gone for the day. So, I plan on calling her in the morning to get those questions answered. And I also wanted to know as far as they said, they gonna open up tomorrow at this location, but the pharmacy won't be open, and I wanted to know what they plan on doing about getting prescriptions out to the elderly.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Interviewing] So, you were out here today for a few hours just giving out food?

JOCELYN: Yes, I'm just giving out food today. I had my kids with me today, so I don't plan on staying out too long. I've been out the past few days though, as far as like downtown and the protests. As far as being down here, I wouldn't really call this a protest. It's kind of what you would call family reunion, everybody getting together and doing what they need in the community, by the community. So, a lot of the outside people don't have to come in, if we don't see what we saw here at Kroger’s outside as you know looting the store, because according to the pictures that I saw it wasn't people from the neighborhood.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Interviewing] How many days were they closed?

JOCELYN: Today was the first full day. Yesterday I think they closed like maybe a little early, but today was the first full day.

KAYTE YOUNG: Talking with MeShorn and Jocelyn in Louisville’s west side, got me thinking about a conversation I had last summer with Sharrona Moore on Indianapolis' east side. After a short break we'll hear from Sharrona about her community garden and mobile farmers' market.

(Earth Eats Production Support Music)

Production support comes from Bloomingfoods Co-op Market providing local residents with locally-sourced food since nineteen seventy six. Owned by over twelve thousand residents in Monroe County and beyond. More at Bloomingfoods dot co op. Elizabeth Ruh, Enrolled Agent with Personal Financial Services. Assisting businesses and individuals with tax preparation and planning for over fifteen years. More at Personal Financial Services dot net Bill Brown at Griffy Creek Studio, architectural design and consulting for residential, commercial, and community projects. Sustainable, energy-positive, and resilient design for a rapidly changing world. bill at griffy creek dot studio

(Gentle Piano Music)

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] Late last summer I drove up to Indianapolis to talk with Sharrona Moore about her garden project which is located in a predominantly black neighborhood in the far east side of the city.

SHARRONA MOORE: Welcome to Lawrence Community Gardens. We have 7.6 acres here. The purpose of the garden here is to really feed the community, so 50% of what we grow goes to area pantries, the other 50% we sell at our local farm stand. So, we provide affordable access to the community. We have chickens, we have bees, we have a hoop house where we're able to grow 365 days out of the year, because we eat 365 days out of the year. So we want to make sure we have food that's growing. This area here is our You Pick For Free section, so the community is able to come in and pick their own produce. Kind of give them that farm-to-table experience that they really will remember, like building memories.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] They also offer a summer youth program that includes skill building and growing marketing and selling fresh produce in the community. I asked Sharrona for a list of what they grow.

SHARRONA MOORE: We have eggplant, zucchini, a little squash, tomatoes, chili peppers, jalapeno peppers, ghost peppers, broccoli, cauliflower, lots and lots of tomatoes - like I said, Swiss chard, bell peppers, cucumbers, horseradish, potatoes, celery, cabbage, lots and lots of herbs. We have onions and garlic, we also have green beans and peas, okra. We have greens too, we have collard greens and mustard greens, and kale.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] We had to cut our farm tour short so that she could meet a client for a haircut at the salon that she runs out of her home. When we arrived, I met DJ.

SHARRONA MOORE: He's my nephew but also my 11 o’clock client. It just gives you a little glimpse at how my day operates, right? So, I don't get a salary for the operating farm. Some people do have salaries, but this is my project, and I'm still developing it. This is how I have to manage my time and to be honest, the garden could be further along, it could be more beautiful, more maintained - if I had the leisure of just being there all day. You know what I mean? But I don't, and this is how I have to... And my kids are homeschooled, so they're in the house working on their curriculum, and if they have questions I have to stop, and I have to answer their questions, and then I have to come back. So, it's just... my schedule is being juggled constantly, all day.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] Sharrona is also the founder of the Indiana Black Farmers Co-op.

SHARRONA MOORE: That was a way for me to find other black farmers. Because the truth is, I will go to classes and workshops, panel discussions and there would never be any black farmers. I would be the only one. And so, when I meet people and I tell them what I do and they were like, "Oh, I didn't know there were black farmers." Well the thing is like, who they think built this country? Who do they think built? We built farming and agriculture on our backs literally, black people did. But we're no longer in that industry as farmers, we have moved away from that.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] Sharrona talked about the limited choices that now exist in neighborhoods like hers.

SHARRONA MOORE: When you go to grocery stores outside of the neighborhood, the selections are far more greater than what we have available inside of the neighborhood. So that just shows again that food equity needs to be addressed on all levels. The Indiana Black Farmers Co-op was founded to support and encourage more black farmers, period. As far as food equality, everybody eats. I haven't met one person of a different race or gender or religion that didn't eat. So that's something that we all have in common. Food should be equal to all people; no matter what your economic status is, no matter what your race, no matter your gender, we should all have access to the same quality of food. And my personal mission is to make sure that in this community with Lawrence Community Gardens that we... the food that we are growing at that farm is staying in this community, to rebuild the community.

Because we know wellness is a choice. It's a choice you have to make a choice to be well, but they also have to have options. And if your options are limited then you're gonna choose what's next best, or all that you have access to. So, we're doing this to make... see that farm stand out there? That's what goes into the community. It goes out into the community. We take SNAP at that farm stand, we take WIC at that farm stand, we buy food from other farmers to add to that farm stand, we also carry staple goods on that farm stand.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Interviewing] What do you mean by staple goods?

SHARRONA MOORE: Rice, beans, things that we can...

KAYTE YOUNG: Like a full meal

SHARRONA MOORE: To make a full meal, yes.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] The far east side of Indianapolis is considered a food desert.

SHARRONA MOORE: I've been a resident here for a long time, and that's why I wanted the garden to be in this neighborhood. But because I live here, and even here where I live, if I didn't have a car, I would be in trouble. Because I would have to walk literally six to eight blocks to get to anywhere where I could even get a cold drink, or a small bottle of milk. So, you know, and then trying doing that if you have a child in a stroller and a toddler, you know. And it's in extreme heat, what can you carry back? You know. What can you carry? How can you... how do you feed your children; can you carry bottled water? No. Not if you're walking. And if there's no buses, there is no buses that goes down 46th street at all. I would have to walk to 42nd street to get on the bus that runs once every hour, or either I would have to work to 38th street. I live off of 46th street. See what I'm saying? There's no shortcut, there are no sidewalks. So, it's just... it’s a struggle. I'm a long time resident of this community so I have seen the transformation - there were access, groceries were here, they closed. You know, and then now they're starting this new program with Lyft where they're gonna drive, they're gonna come pick up neighbors and drive them to the grocery stores that left the community to begin with. It's some systemic issues going on here that need to be addressed as well, but until then, until we get it all figured out, Lawrence Community Garden is still going to be trying to reach the people with the food that we're growing. So, and that's just all that we can do.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] Our interview was cut short due to an unexpected issue that demanded Sharrona's attention. Her nephew DJ had this to share before I packed up my gear.

DJ: I grew up over on 46th and Arlington, and we had a Kroger over there. And I've been going to that Kroger since I was probably 10 years old. So one day for the first time, maybe two or three years ago, I went to the Kroger's up on Binford road, and I saw meats and vegetables and fruits that I'd never seen in my life. And it's literally probably 10-15 minutes away, you know, which is in a different neighborhood. They had a selection of organics, I'd never seen that many green labels ever. I didn't even know that some of that stuff even existed. You see the meats fresher, the cuts are thicker, the fruit like I said, it's just fresher fruit. You see stuff that you never seen, starfruit, and you know things that I've always seen on TV. And I'm like, "Wow, they got this, they got that." Fresh aloe vera, you know you can buy a whole aloe vera, and then cut it and use the inside for skin care and stuff like that. So, I just didn't realize the difference until I started venturing outside of my neighborhood.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] That was DJ, Sharrona Moore's nephew. I hope to reconnect with Sharrona later this summer to hear about adjustments they've made in their programming due to the coronavirus restrictions. Find links to her work at EarthEats.org.

(Gentle Piano Music)

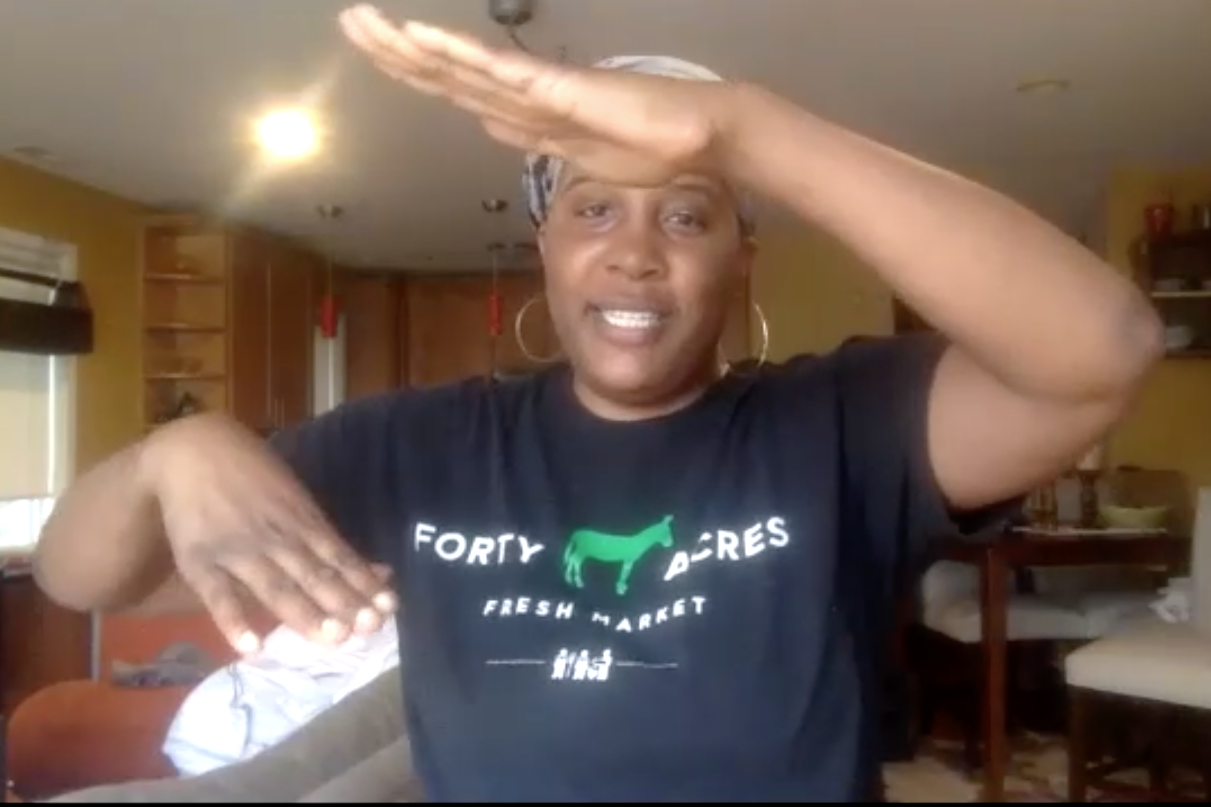

In an interview last year with Leah Pennimen of Soul Fire Farm, she voiced objections to the term "Food dessert". This year I called Liz Abunaw in Chicago Illinois, she's the owner and operator of 40 Acres Fresh Market in the Austin neighborhood on the west side of the city. Her project was recently featured in Forbes magazine and I was interested in her perspective on the role of grocery stores in predominantly black and low-income neighborhoods. I asked for her thoughts on the term "food dessert".

LIZ ABUNAW: It makes it seem as though the condition of food not being healthy affordable food, not being readily accessible in a neighborhood, is just a matter of natural occurrence. It holds no one responsible, there's no actors at play that have the situation. We don't blame things like structural racism, we don't blame white flight, we don't blame redlining, we don't blame policy, we don't blame the businesses and the developers who determine which neighborhoods get their investment and which ones don't.

So, I prefer the term food apartheid, because there's clear inequality and nine out of ten times it breaks down along racial lines. And here the city of Chicago it's predominantly black neighborhoods and some brown neighborhoods where, it's like, I can't find food. And it's particularly egregious in black neighborhoods partially because we're so underrepresented in the grocery industry.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] And Liz Abunaw is working to change that.

LIZ ABUNAW: 40 Acres Fresh Market is a grocery startup in Chicago that focuses on increasing access to affordable fresh food in underserved neighborhoods. We currently operate on the westside of Chicago with a focus in the Austin community. And we are black owned, community built. We are all about not just bringing good food to the community, but everything that healthy food retail brings with it - the jobs, the change in the neighborhood environment, and of course the greater access to healthy food.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] The model for 40 Acres right now is to offer produce boxes at various price points which are pre-ordered and delivered. It's similar to a CSA or Community Supported Agriculture. But Liz is not a farmer, and they aren't necessarily purchasing from local farmers.

LIZ ABUNAW: One of the things people don't realize is that there's two sides to this quote-unquote "food justice issue". There's the supply side, and that's really about how food is grown, it's about the environmental impact of our food. It's about the economic impact of how our food comes to market and that's like, how is it grown, are farmers getting a fair wage, are people who pick the food getting a fair wage. When you're buying cheap food it's because of economies of scale, and some large farming corporation is probably paying people pennies to pick your strawberries, pick your food, it's probably using up tons of water, it's not the most environmentally friendly. But that is how you get cheap food. So, when we talk about food justice on the supply side, it's really about raising the value of food for what it's really worth sustainably producing. On the other side of food justice is the accessibility side. It's the demand side. It's making sure that there's food infrastructure in a neighborhood. That the food is affordable, that it's of good quality, that multiple methods of payment are accepted; it's all about accessibility. And what you start to realize is that food justice on the supply side is like goes this way, and food justice on the demand side goes this way, and they don't really meet in the middle. I focus on the demand side. I focus on making it accessible, making it affordable.

KAYTE YOUNG: [Narrating] Food justice, economic justice, racial justice, it's all so much more complicated than it seems at first glance. Liz says the Austin community has seen some damage from the recent protest in Chicago, but she says the community has pulled together to clean up and to take care of each other. It's rarely just one thing, or the other; workers’ rights, or affordable food, destruction or care. Sometimes it can be both / and.

(Earth Eats Theme Music)

That's all we have time for today. Thanks for listening. You can find out more about all of these people and their projects at EarthEats.org

RENEE REED: The Earth Eats team includes Eobon Binder, Chad Bouchard, Mark Chilla, Abraham Hill, Taylor Killough, Josephine McRobbie, Daniel Orr, The IU Food Institute, Harvest Public Media and me, Renee Reed. Our theme music is composed by Erin Tobey and performed by Erin and Matt Tobey. Earth Eats is produced and edited by Kayte Young and our executive producer is John Bailey.

KAYTE YOUNG: Special thanks this week to MeShorn Daniels, Jocelyn, Sharrona Moore, DJ, and Liz Abunaw. Production support comes from Insurance Agent Dan Williamson of Bill Resch Insurance. Offering comprehensive home and auto, business, and life coverage, in affiliation with Pekin Insurance. Beyond the expected. More at bill resch insurance dot com. Bloomingfoods Co-op Market providing local residents with locally-sourced food since nineteen seventy six. Owned by over twelve thousand residents in Monroe County and beyond. More at Bloomingfoods dot co op. Elizabeth Ruh, Enrolled Agent, providing customized financial services for individuals, businesses, disabled adults including tax planning, bill paying, and estate services. More at Personal Financial Services dot net