The Indiana murals by Thomas Hart Benton are one of Indiana University's major attractions. The panorama representing the history of the state was commissioned for the Indiana Hall at the 1933 World's Fair in Chicago, and ultimately installed in several buildings on the Bloomington campus. A young Abe Lincoln and hooded Klansmen are easily picked out, but others aren't.

One of the mural's more obscure figures is the subject of a new book and exhibition at the Indiana State Museum.

Hiding In Plain Sight

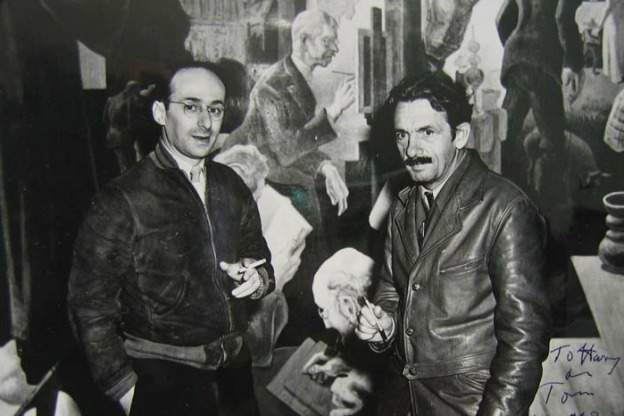

The museum's Curator Emerita of Fine Arts, Rachel Berenson Perry and I are scanning the Benton murals in the grand lobby of the IU Auditorium to locate the subject of Perry's latest book, William Forsyth: The Life and Work of an Indiana Artist (IU Press, 2014)-

"I wonder how many people actually realize that that's him," ventures Perry.

We've found Forsyth in the middle of Cultural Panel number 8, the section dedicated to leisure and literature, hung over the staircase on the north side of the lobby.

"It looks like he's hunched over with a very small brush," Perry notes; "hunched over an easel painting and leaning forward."

And this is not the way Forsyth's biographer imagines him, at all.

"I just never picture him painting like that," Perry reports. "He was gestural, he was uninhibited and he had very almost violent brush strokes sometimes."

According to Perry's research, the portrayal doesn't accurately convey Forsyth's body language or working method. But the very fact of his inclusion in this definitive pictorial history of the state might be the ultimate testament to his personality.

"Only the strong persist." Perry reminds me.

That's the subtitle of the Forsyth retrospective Perry has curated at the Indiana State Museum. Forsyth had to have been strong, and persistent to have turned up in the mural. He was 78 by the time it was painted, and better known by then as a teacher than an exhibiting artist.

The Undersung Member of the Hoosier Group

"It is kind of strange that Forsyth was chosen instead of T.C. Steele," notes Perry, "who was of course the dean of all artists in Indiana."

But Steele had passed away in 1926, so seven years later when the mural was being painted, Forsyth was the last living member of the fabled "Hoosier Group"-five painters who started getting noticed around 1894, "for painting their own home territory," Perry explains, "things that actually hadn't ever before been noticed for being particularly beautiful."

Though comrades in promoting the Indiana landscape, "Forsyth was always jealous of T.C. Steele," Perry concedes, "even though they were pretty good friends."

Such good friends, in fact, that Forsyth lived with Steele's family while both artists were studying in Munich. "But he was always writing letters back," Perry explains, "like, 'Oh, poor T.C. Steele, he's getting a little better and he's trying really hard, but he's never going to be much of an artist!'"

Despite Forsyth's prediction, Steele returned from Munich to become Indiana's premier portraitist, and Forsyth, a lifelong teacher. Both men became known for their landscapes painted on-site across Southern Indiana. But, as Indiana University Art Museum curator Nan Brewer explains, Forsyth kept pushing past the impressionistic look of the Hoosier Group. "There's more of a range of stylistic approaches in Forsyth than in Steele," says Brewer, "who, once he comes to the Impressionist style, really adheres to that for the rest of his career."

The Go-Figure Modernist

"You can say, 'I have a Forsyth,' " Perry elaborates, "and then someone comes and looks at it and says wow, that's a really different one, or I wouldn't have ever thought that was a Forsyth."

Forsyth was experimental, but he identified himself as a traditional painter. So, for example, when he attended the Armory show (the 1913 exhibition that introduced European modernism to the US), he was "horrified," Perry concedes. "Part of that was the feeling that a lot of the modern artists hadn't paid their dues the way he had and the way the Hoosier Group had. But he seemed to have some misgivings later. I think some people would identify him as a modern artist if they were to look at some of those paintings that are very gestural and just barely representational."

Take The Red City, the jewel of the retrospective. The prize-winning 1913 canvas marks a shift in his approach-

"This was completely done from Forsyth's imagination," Perry elaborates. Â "He stopped at one point making paintings from looking at things to summoning his own imagery from his own imagination, which is a very modernist sensibility."

It might be a stretch, but Forsyth's latent modernism may have secured his place in history-Benton's version at least. Forsyth was one of the rare members of the Indiana art establishment who weren't outraged by the choice of a non-Hoosier, modernist painter for the World's Fair mural project.

"Given the changes in Forsyth's own style over his career," Brewer speculates, "he would have understood this progression in American artistic styles."

The portrait may have been Benton's way of thanking Forsyth for giving his blessing. "To really thank him visually for his support of him," explains Brewer, coauthor of Thomas Hart Benton and the Indiana Murals (IU Art Museum and IU Press, 2000). Â "There wasn't as much negative sentiment about Benton after William Forsyth because of his stature within the arts community."

But it was more than just a political move, Brewer suggests.

"He puts William Forsyth center stage in a panel devoted to the art and culture of the late nineteenth century into the early twentieth century in Indiana, so he recognized his importance and the importance of the Hoosier Group in really raising the profile of Indiana on the world stage."