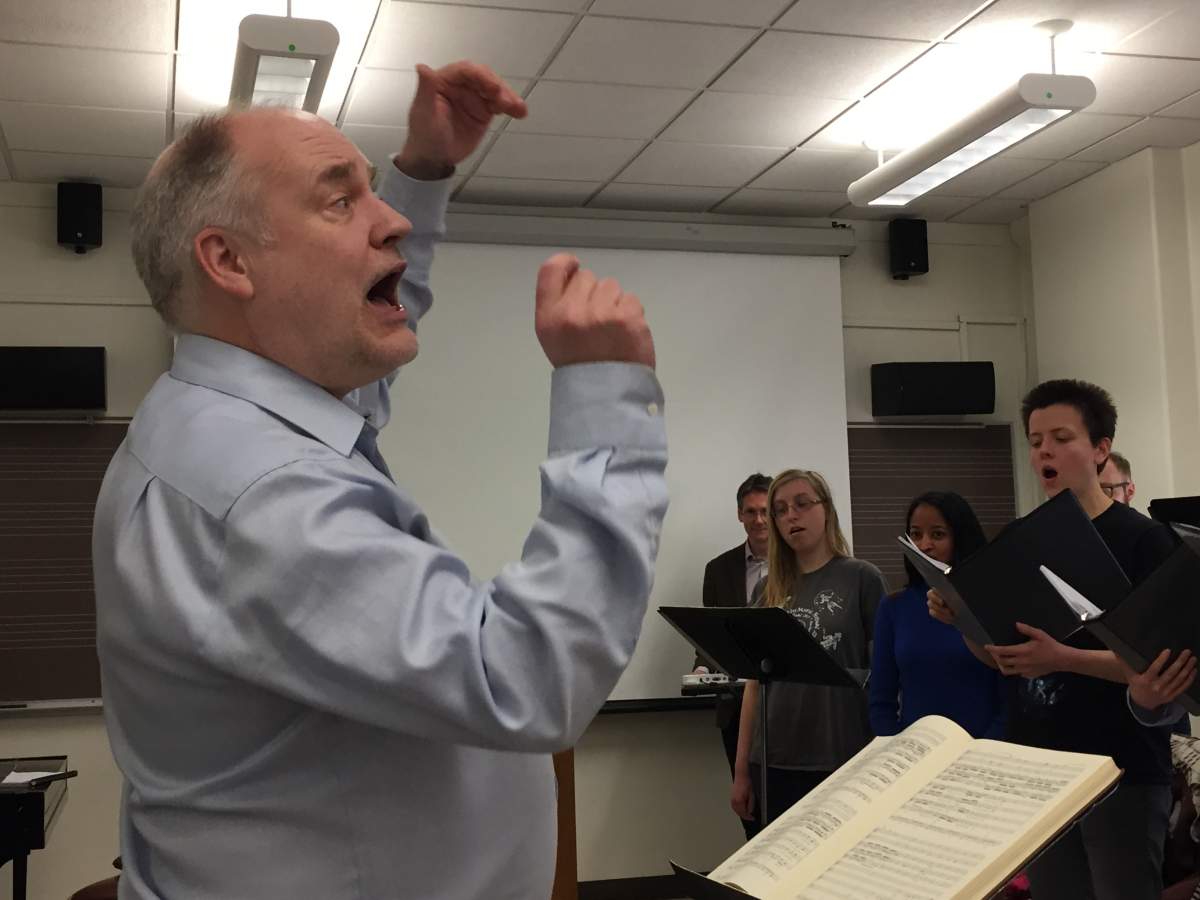

In a medium-sized classroom in the Jacobs School of Music's Merrill Hall, a group of singers is forming. They're chatting and thumbing through their musical scores as they take their places for a rehearsal. The piece they're about to work on is the Johannes-Passion, or the John Passion, by J.S. Bach. Today, they're meeting John Butt, the guest director of their upcoming performance, for the first time.

John Butt is a conductor, organist, harpsichordist, and scholar. He's been on campus nearly a week giving masterclasses, playing in concerts, and rehearsing with the instrumentalists for this same performance, but he still seems to have plenty of energy as he prepares to take the members of the Concentus vocal ensemble through the opening number of this monumental work for chorus, orchestra, and soloists.

"The word, passion, comes from the Latin word for suffering," Butt says, "so it's a narrative that relates to the suffering of Jesus, leading up to the crucifixion and just beyond. In other words, it concerns one of four stories from the four gospels, each of which tells the story in a slightly different way. But it's the same basic, tragic story. A Passion is a musical setting of that story; either just the biblical text alone, or sometimes it might be a rewriting of the biblical text. Or, in the case of J.S. Bach, the entire biblical text with other texts wound around it to give it more meaning and color."

Butt adds, "Bach was very fortunate to come at a period when composers were setting much more elaborate types of Passion, integrating elements of opera. And I think it is important to realize that it's not the case that Bach's Passions are operas-in-waiting, but that operas actually are part of their background; that Bach saw operas and saw the power of opera in moving an audience, and therefore thought that can work very well in the context of a congregation of a church. In other words, Bach uses every style of music at his disposal to give this narrative. It's as if Bach is taking the newest technology of the age-opera, recitative, aria, and choruses and chorales, as well-and winding them all together to give what you might think of as a sort of multimedia version of the Passion story."

Butt continues, "understanding the mechanics of the music, its rhetoric, the way it reinforces ideas, reinforces views, and, in John's Passion in particular, opposites. The whole text of John's gospel is based on complementary pairs of opposites: below, above; Jesus completely abased, but at the same time glorified as ruler. These things are brought out very clearly, and there's no better medium than music for bringing out that contradiction. Recognizing those sort of mechanics and how the music relates not just to the actual text but to the broader context, I think, is a very useful way of unfolding the different levels of meaning and, indeed, emotion in a work of this kind."

John Butt is not the only guest artist who has come to the Jacobs School to work with the students and faculty on preparing this weekend's performance of the John Passion. Violinist Bojan Cicic is also on campus this week to perform chamber music, teach lessons, and serve as the orchestra's guest concertmaster for the performance. Cicic was recently appointed Professor of Baroque Violin at the Royal College of Music, and, like John Butt, he is committed to the notion of using a kind of heightened rhetorical awareness to train the next generation of instrumentalists.

"It is a way to get away from the notes on the page and think about what the whole point of baroque music was, which was to stir passions, or affects," Cicic says. "We're often very focused on technical presentation of a piece that we're performing that would probably be very foreign to the performer of the 17th and 18th Century. The reason why I fell in love with baroque music was the interpretations of particularly 17th-century works where the musical language is so much more direct with its message. The approach is so much more immediate, and I definitely responded to it much more quickly than the music that I was doing at the time, which was studying modern violin at the academy."

Both Bojan Cicic and John Butt have performed with numerous musical groups. John is the director of the acclaimed Dunedin Consort. Bojan also formed his own group, the Illyria Consort. So neither of them are strangers to working with professional early music specialists. And both were pleased to have the opportunity to work with the students at the Historical Performance Institute.

"The level is really fantastic," Cicic observes. "I've enjoyed very much either individual lessons or the chamber music that I have experienced, because it seems very, very serious. People are really prepared. They bring music not in modern editions. They are really trying to get into 17th-century editions-potato prints, as we call it-which just makes it harder for our modern eyes to play all these very fast notes, in particular, on a violin. But that's very, very admirable that they are trying to go as close as they can-also visually-to the student musicians that lived in the 17th and 18th Century."

"I think, as an academic, one of my great interest is how you connect things," Butt adds. "How you connect different subjects, one thing with another. And a department like this which has a great emphasis on early music performance has the automatic sense of connection. So they are already halfway there, in a way. So, anything I can do, then, to try and encourage them to use what they've got and not to rely on what they've been told, but to take what they've been told as a starting point and having a flexibility. I think that's the crucial thing. Particularly if one thinks of the employment prospects for people like this. They're not all going to go into one particular style of performance in one particular style of ensemble, so anything, then, that gives them that flexibility is something that I'd be very keen to encourage."

J.S. Bach's Johannes-Passion will be performed this Sunday, March 4 at 8:00 pm in Auer Hall, on the IU Campus. It will feature the Historical Performance Institute's Baroque Orchestra, the Voices of Concentus, guest concertmaster Bojan Cicic, and guest director John Butt.