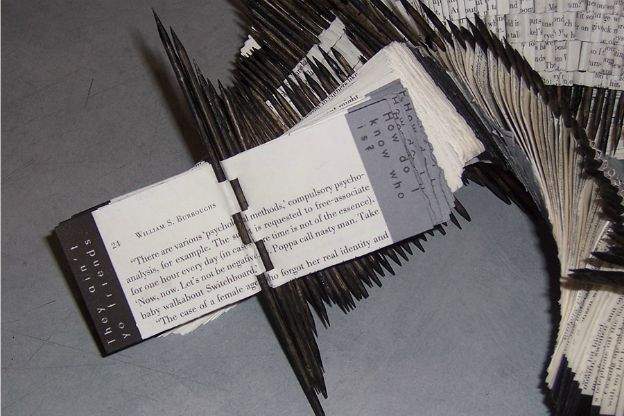

Artist's books created by students at the Herron School of Art & Design currently on view in the foyer of the Fine Arts Library at  IU-Bloomington explore the expressive potential of the book format. Part of Indiana University-Purdue University-Indianapolis, Herron offers a minor in book arts within the printmaking department, but the courses draw students from sculpture, photography, painting, and all the other areas Herron offers.

"We have with this medium the luxury of tying in to an icon," explains Karen Baldner, who teaches within Herron's book arts division.  "Everybody knows what a book is."

But not everyone knows what an artist's book is. In what happens to be the 15th annual exhibition of Herron student work in the book arts on the Bloomington campus, there are plenty of objects that bear little resemblance to books as we know them.

A Book You Can Wear Is A Book You Can Hide

"When you see a structure that doesn't look like a book here, that's done consciously," explains Baldner.  She points out a few of these "unbooks" on display:  "For example, we have a very round object here, with no text. And this," Baldner continues, "actually folds up, collapses into a little piece that looks like candy. And this one here is a pyramid, with stories folding into each other. And yes, this is meant as a bracelet."

There's a tremendous excitement about being at the forefront of discovering a medium that has enormous potential on the expressive level.Â

Yes, a bracelet. That, somewhere in its DNA, references the form, and history of the book

"It's a bracelet-like structure with acorns opened up into its two halves," Baldner explains, "and out of these two halves comes an accordion-style tiny, tiny book with red lettering on it that can only be read when you pull the accordion out."

It's a cryptic object, but one that follows out of the long tradition of miniature, wearable books.

"It's actually age-old," Baldner elaborates, "and started with persecution, especially religious persecution. And it has a lot to do with taboos and hiding books, and the tradition of making Bibles and Korans very tiny, so you couldn't even see them. Or, put [ting] them into clothing and wear[ing] them."

The intimacy of the book-that it is something you can wear on your body and hold in your handis what lends this art form so readily to personal expression. In fact, the intimacy of the format serves to attract artists who normally work in a different field. Although her primary medium is sculpture, Shana Reis made several books-on display here-that explore her experiences as a gunner on the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Writing It Down On The Shirt Off Her Back

"She did not quite come out with her story before," explains Baldner. "This was a good place for her to get to her story and then pursue it there. So in her larger sculpture it doesn't totally and obviously go to her processing of her experience. But here it does very directly."

Reis processed her combat experiences in the form of three books that collapse into a slipcase. One of the stories unfolds on pages made from her uniform. Several of the military veterans on the Herron campus got together to run their uniforms through the paper pulp beater.

"It's a ritual in itself to break the uniform down," observes Baldner. "The vets get together and break it down and that's a big moment for them. And then you put it in the beater and it becomes a communal pulp. It's a very cathartic thing."

And the material the process generated served as the perfect vehicle for the story Reis needed to tell about war and its personal aftermath. "She doesn't mince words at all," concedes Baldner. "It's not all that pretty to read."

Does this art form lend itself to dark or elegiac stories, simply because of the fact that people are reading virtually or digitally so much these days, and the physical book has become a forlorn artifact, or at least a bit of an antique?  Baldner concedes that she had that concern decades ago, but thatthanks in part to the re-appropriation strategies so common within postmodernist art practice"there's this tremendous excitement about being at the forefront of discovering a medium that has enormous potential on the expressive level. Imagine a vessel being vacated and then re-inhabited in a new purpose. Students who are engaging in this know that they are reinventing the wheel!"