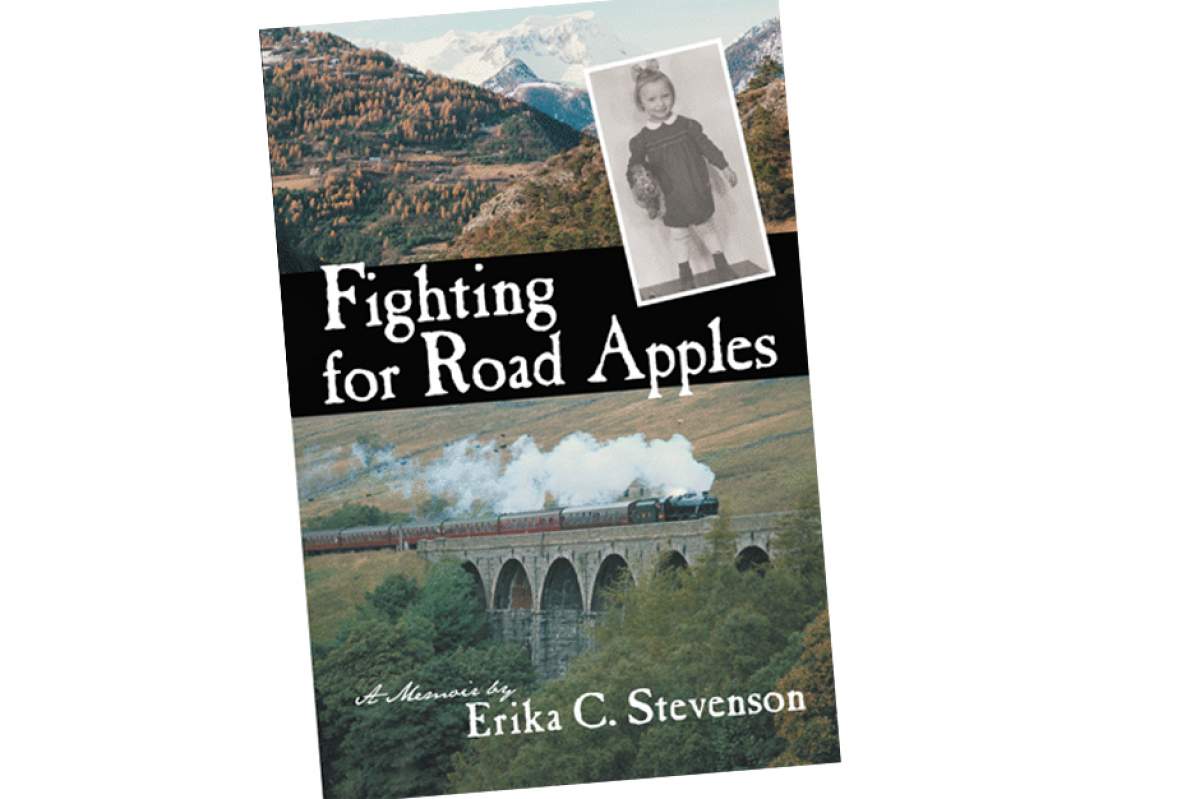

Ten years ago, Bloomington resident Erika Stevenson was diagnosed with stage III colon cancer. Fearing she might not survive the disease, she decided to write her life story. The result is her memoir, Fighting for Road Apples.

‘It should be discussed'

The book begins in 1946 when her family-consisting of herself at age 6 and her parents-were among the three million Germans expelled from the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia.

"I wanted to remind people," she says in a soft German accent, "‘This is what happened.' In the Czech Republic today, no one really knows about the Sudeten Germans, because the old generation has died out. The younger generation, they have not paid too much attention to their history. People I talked to about this never heard of it.

"This was a horrible event. These people got thrown out of their homes. Thrown out of their country where they had lived for generations.

"So that was my main purpose. To do the expulsion, which was hushed up. I thought, ‘It should be discussed.'"

An "F" on Her Forehead

Her family was always on the move and she grew up stigmatized as a Flüchtling-German for "refugee."

"For many years, even as a teenager, it was like an 'F' was on top of my forehead. I felt always intimidated. I felt that everything happened-especially the bad things-because I was a Flüchtling. And that's why my life didn't go like other children's lives. I always felt disadvantaged because of that."

In 1945, most Sudeten German men were in concentration camps, including Stevenson's father. This gave the Czechs free rein to, as Stevenson puts it, "terrorize the women and children." It was then that two Czech soldiers came to the home of 5-year-old Erika and her mother, confiscated their possessions, and gave her mother a new name.

"They took everything of value. My mother's gold earrings, my father's watch. They even took my mother's wedding band.

"My mother's name was Mitzi, but her name was really Maria. And our last name was Veit. They came and said, ‘You are now Marie Veitova.'

"Also, they said, "You will now work for a Czech family.'"

Thrown into a Fire

The Czechs told Stevenson's mother that she would work for the family as a domestic. The lady of the house wasn't happy about Maria bringing her daughter along, and said that she would "tolerate" the girl. But the Czech family was anything but tolerant.

"They mistreated us very badly. The children [of the house] kicked her and hit her if didn't do something fast enough.

The Czech family had five children, all boys. At one point, they lit a small bonfire outside, called Erika over, and forced her into it.

"They threw me into the fire because I was a Nĕmec girl, which is ‘German' in Czech. I fell, and my mother came running and got me out of the fire. The mistress [of the house] said I had to go because I am causing all these problems for her boys."

For many years, she bore a scar from that incident on her left hand.

"You can feel still a little bit of it, but it's actually gone away. But for the longest time when my children were little they would say, ‘What is that?' and I would tell them about some mean little boys, when I was younger. And they would always kiss it."

Nearly Raped by a Russian Soldier

The book describes an incident that occurred when Erika was 5-years-old and Russian soldiers were camping on her parents' property, a horse farm that the soldiers used as their headquarters. Her mother, who was 24, concealed her youth to get around without getting molested.

"My mother had to walk by the tents where the soldiers lived. The Russian soldiers were known as raping women and children. So she went into the horse stables and rolled herself in the manure so she would smell bad. And then she limped through that area where they were. She completely covered herself with a kerchief, old clothes, so she could not be recognized."

Nevertheless, her mother was nearly raped by a drunken Russian soldier. The scene is still vivid in Stevenson's mind.

"The soldier hid inside the house. My mother and I were going upstairs where we lived, and all of sudden he jumped down, and grabbed my mother. He didn't speak German so he motioned for her to get down on the floor. She didn't want to, so he pulled out his pistol and put it on her temple. Whatever he said, we couldn't understand, but it was very clear what he wanted.

"He unbuckled his belt and I knew he wanted to hurt my mother. I cried and I begged him [not to]. She held on to me all the time he was trying to push her down.

"All of a sudden, out of nowhere, one of the officers came, took the pistol from him, and threw him down a flight of stairs, and apologized.

A Flüchtling No Longer

After the war, things improved. When Stevenson was 18, she got a job at a bank, and her sense of identity changed.

"The bank sent me to a seminar, and that was the first time I was put in nice accommodations. When I came back home, I tell my mother all these things, and she says, ‘See, even when you're Flüchtling, you can achieve things. It's you who achieves. Not what you were, or where you came from. It's your hard work.'"

Stevenson married an American solder and they immigrated to America where she got a college degree in accounting. They raised three daughters, and she made a career in the automotive industry. She credits her success in life to hard work, and she hopes readers of her book will be inspired by her story.

"People can survive and make something of themselves, even though they were crushed to the bottom. You can get up, and start walking. That's what I did. I'm truly an example of that."

Erika Stevenson is fully recovered from her colon cancer. She is working on a second volume of her memoirs that will pick up her story with her life in America.