Alex Chambers: For a few decades there, there was this old house in St. Anne, Illinois, a bit south of Chicago, that had a symphony in it. There was other music too. Violin concertos, and more. I mean, you couldn’t hear the music. It was all on paper. Dozens of scores by the twentieth century composer, Florence Price. The few people who’d been paying attention figured they were lost for good. They’d heard she wrote a fourth symphony, but it would go forever unheard.

Price was a composer in the first half of the twentieth century. She’d won awards, her work was played in Detroit and Chicago, she was inducted into the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. But even if you’re a classical music fan, you probably haven’t heard any of her music.

It’s hard to pin down why. Not all of it was stuck in the attic of what was once her summer home. Is it because she just wasn’t as talented as Copland, or Gershwin, or Ives? Or were her talents dismissed, because she was a Black woman?

Alejandro Gómez Guillén: I don’t think I can sit here and tell you that the color of her skin wasn’t an issue in her not being programmed more often.

Chambers: That’s Alejandro Gómez Guillén, the artistic director and conductor of the Bloomington Symphony Orchestra. He says people can get pretty caught up in deciding whether something is objectively good or not.

Gómez Guillén: I wonder whether, if you try to quote unquote compare Florence Price’s music to let’s say other contemporary American composers, let’s say to a Copland, and assign value of what’s better or what’s worse, or what’s lesser, what’s superior, you get into really a conversation of apples and oranges and I think you miss the point. I think there may have been some of that kind of thing going on too, you know? Well, this doesn’t sound American enough, or it sounds too American, is she quoting spirituals, why is she doing that?

Chambers: Price was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1887. Her father was the only Black dentist in the city. Her mother, a white woman, was a music teacher.

Gómez Guillén: She actually had the opportunity to be trained in music from an early age, which was not necessarily the norm.

Chambers: But she still had to deal with racism. There were years when she found it easier to pass as Mexican than let people know one of her parents was Black.

Gómez Guillén: Which of course opens up this whole conversation of the times that we’re living now, and it feels very poignant and very strong to me that we’re talking about so many decades ago, she was struggling to not only hide her identity but redefine it in a way that would make it more acceptable, yet using another heritage, another cultural heritage, as a reference.

Chambers: She wasn’t always trying to hide. She took her own roots seriously. That fourth symphony, for example. The one that was stuck in the attic? When she got to the third movement, she took things in her own direction. A symphony’s third movement is usually a dance. A minuet, maybe a scherzo. Price used a Juba, a dance that enslaved people brought to the South Carolina coast.

Gómez Guillén: So I feel like she’s very strongly making a statement, like, not only am I writing music that is representing my own voice, but I’m also carrying the voice of all these people that came before me.

Chambers: Price’s fourth symphony was pulled out of the attic in 2009, but it didn’t get performed for another nine years. It’s been recorded just once, in 2019. That’s what we’re listening to now. It’s had eleven performances. Total. Not one of those in Indiana.

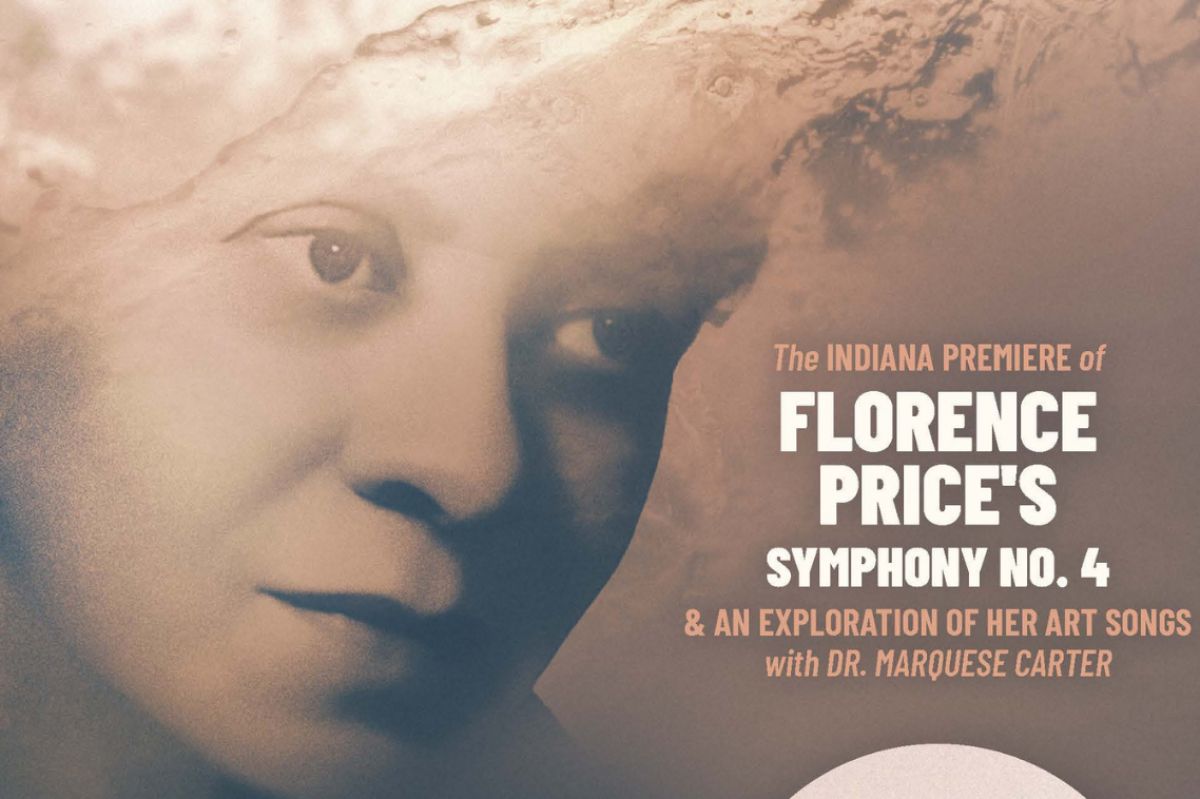

But as you might have guessed, that’s about to change. The Bloomington Symphony Orchestra will be sharing its Indiana premiere of Price’s fourth symphony, along with some of her art songs, in their next concert in late October.

The symphony has been working with Dr. Marquese Carter, a tenor, cultural activist, and Florence Price scholar. At the concert, Dr. Carter will perform a handful of Price’s art songs. Between the songs, they’ll discuss what each song represents in the context of Price’s life

Gómez Guillén: Florence Price as a mother, Florence Price as a pedagogue, Florence Price in some ways as a cultural ambassador herself.

Chambers: After intermission, they’ll present some excerpts from the symphony, and then perform the symphony itself. Along with the in-person concert, there will be a parallel live stream, so you can watch and listen wherever you are.

Gómez Guillén: And again I challenge ourselves to let it be the kind of event that we do more and more of. That it is not a one-off, that this conversation of greater representation in the orchestral field, in the symphonic field, needs to be more and more important, and I hope people will go out of this with a renewed sense of purpose in that

Chambers: The Bloomington Symphony Orchestra will be performing the music of Florence Price on Sunday October 24 at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater. More information can be found at bloomingtonsymphony.com.

For WFIU Arts, I’m Alex Chambers